012

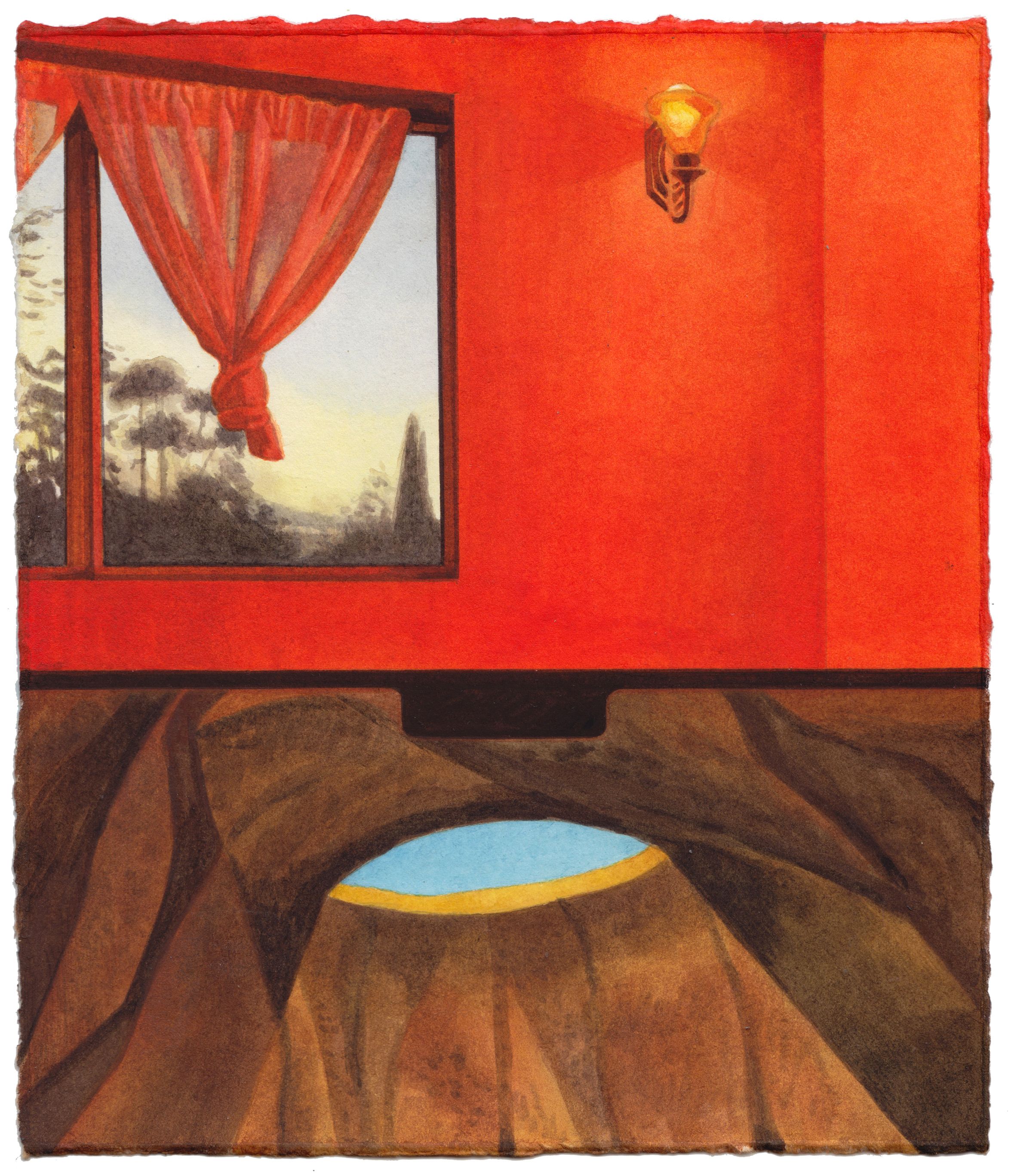

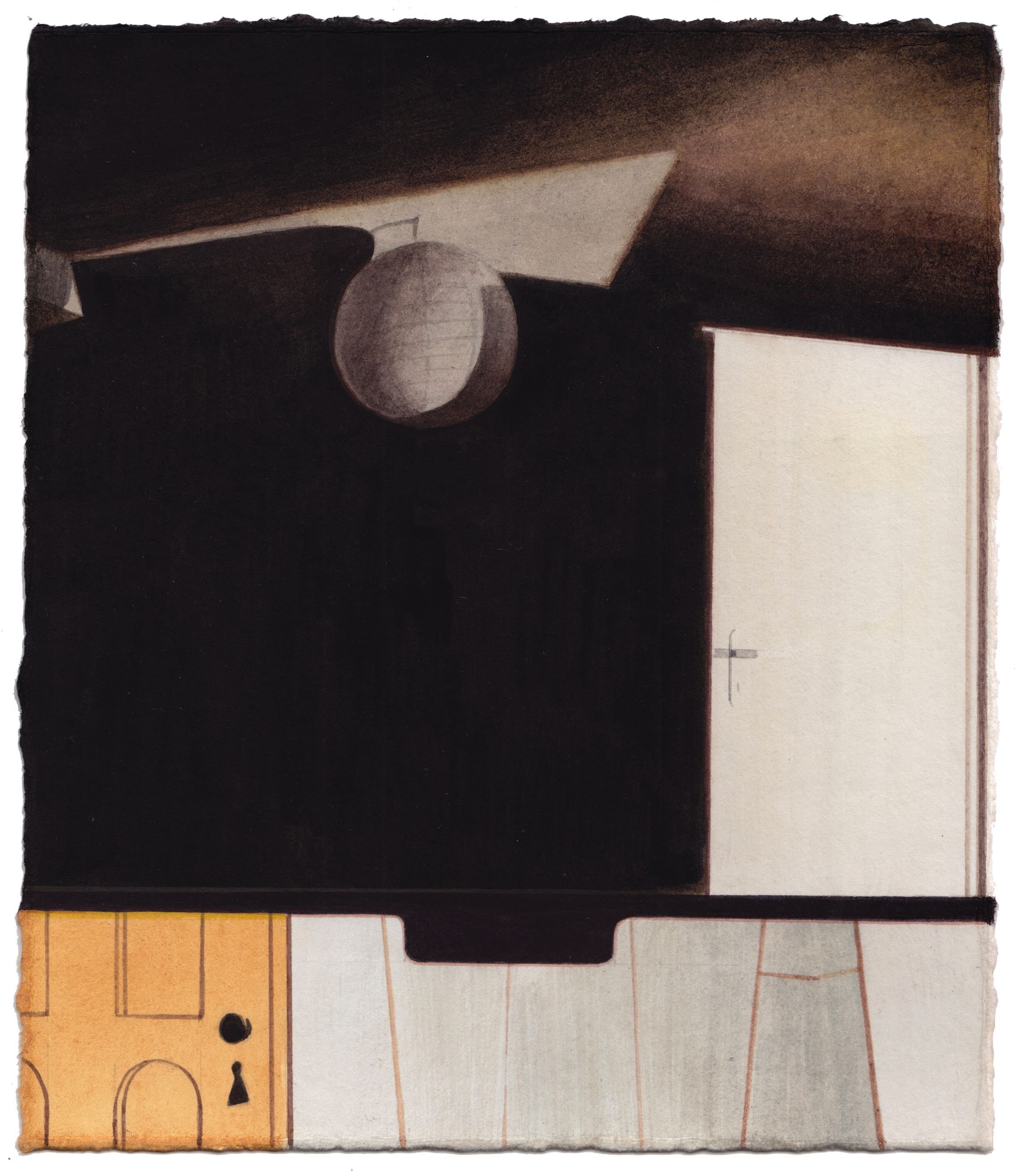

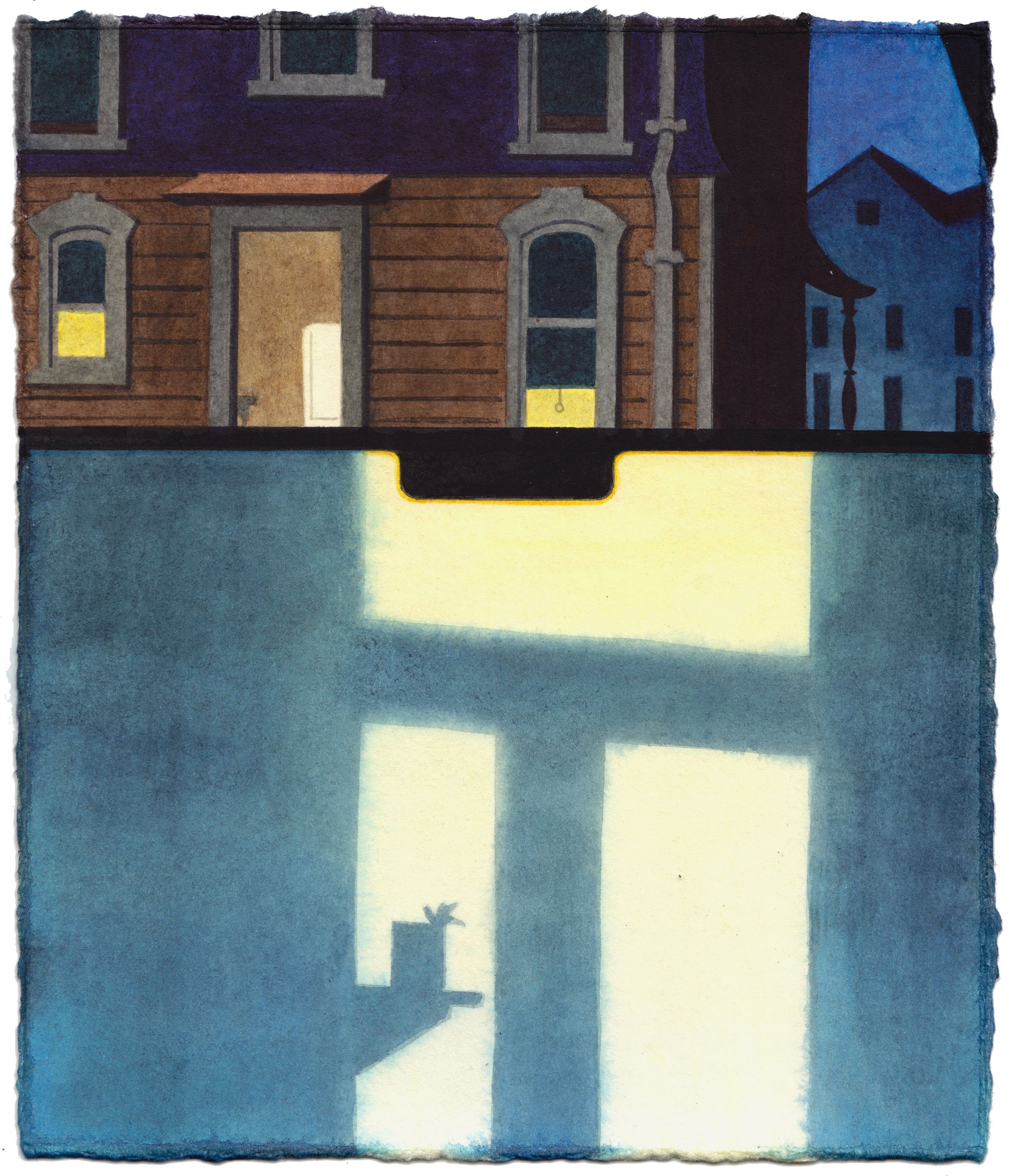

Ins and Outs

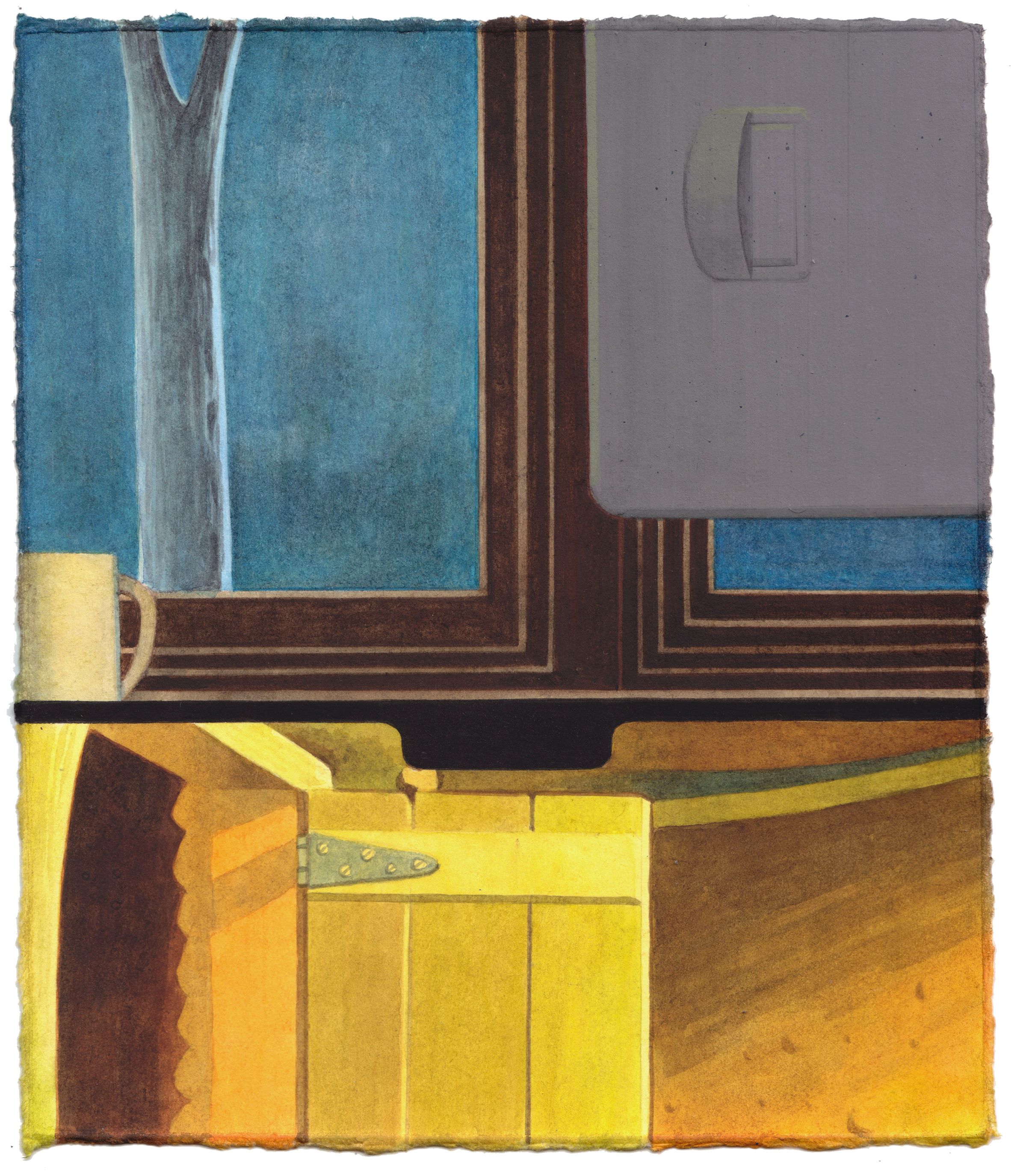

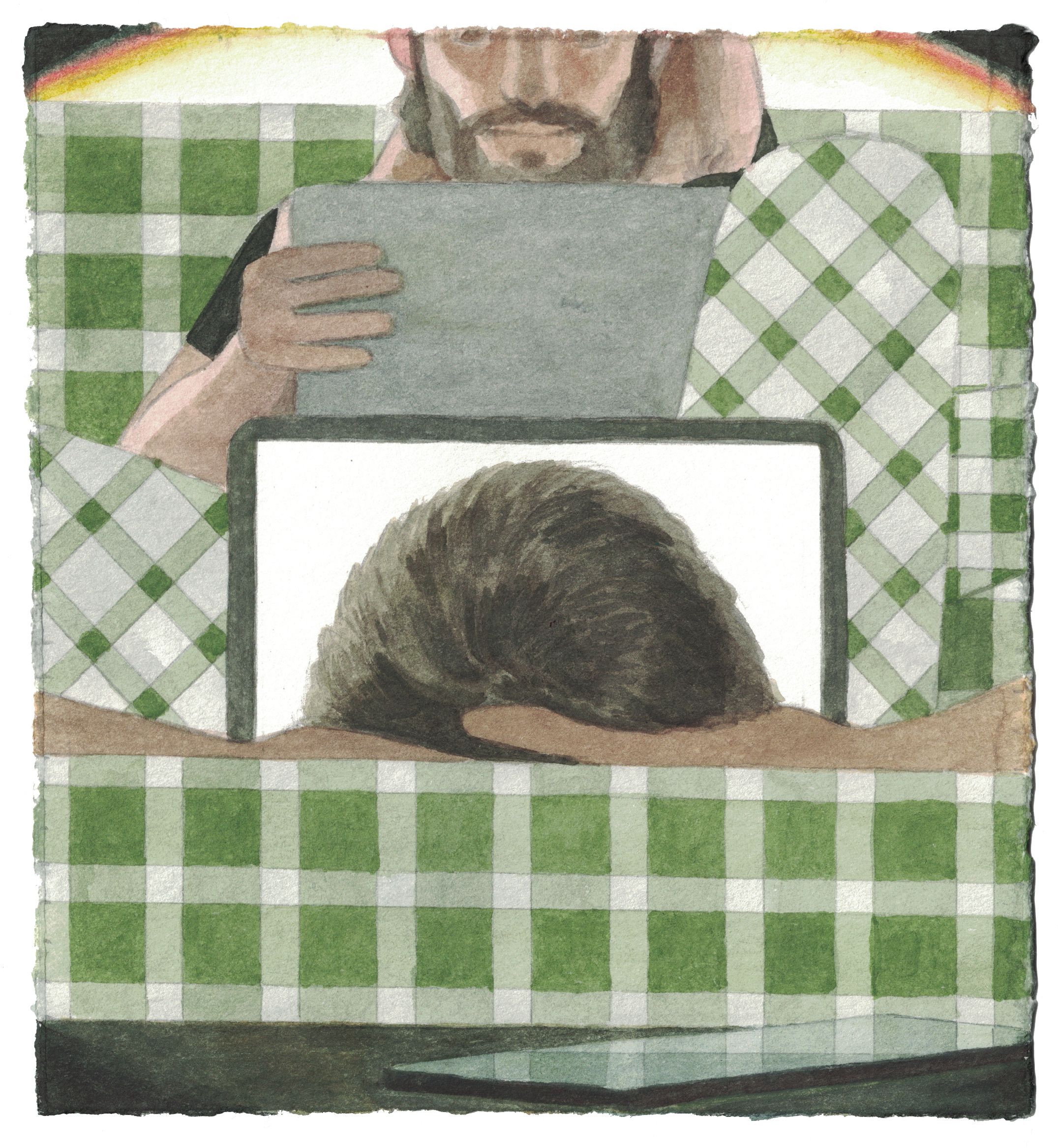

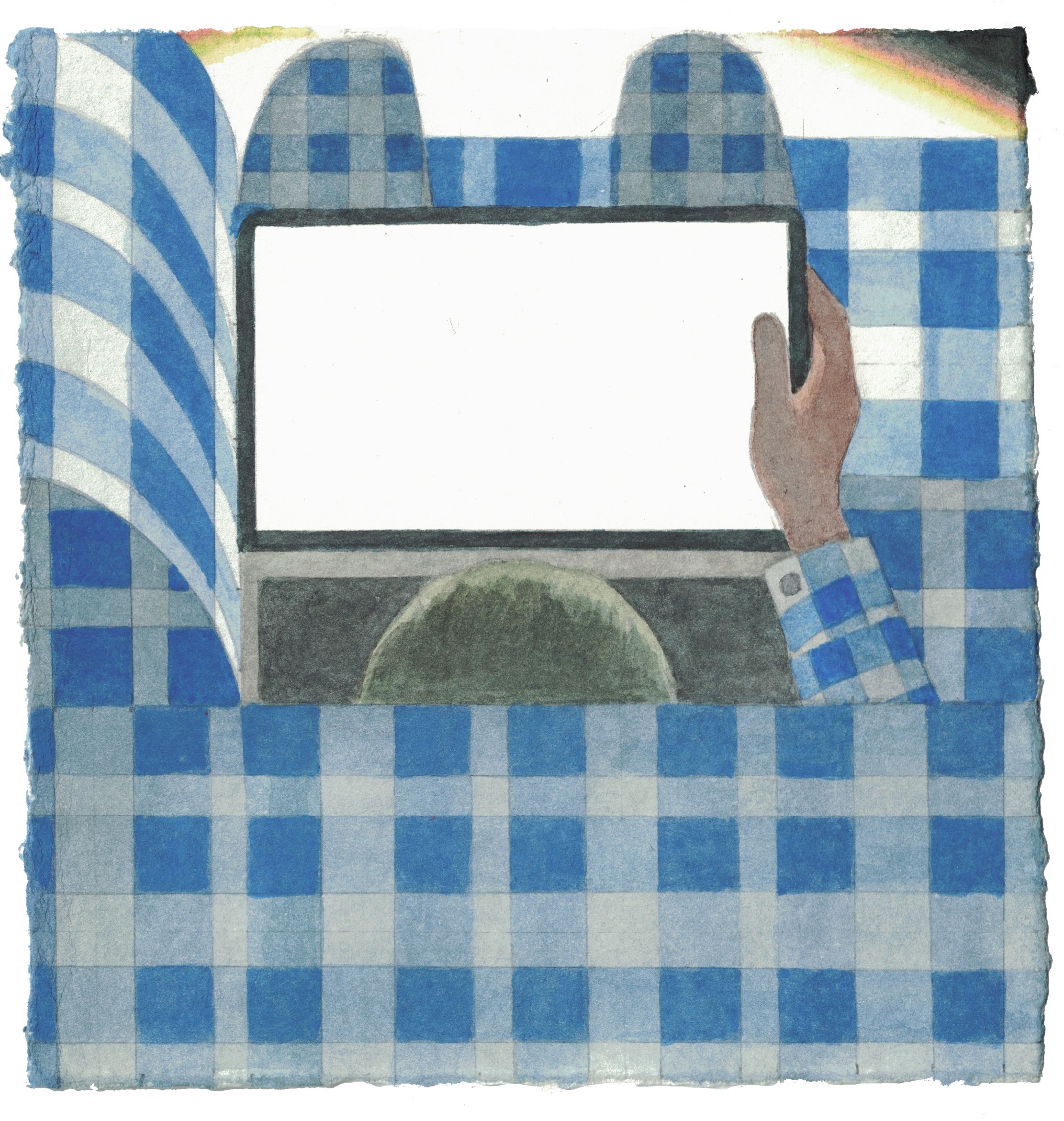

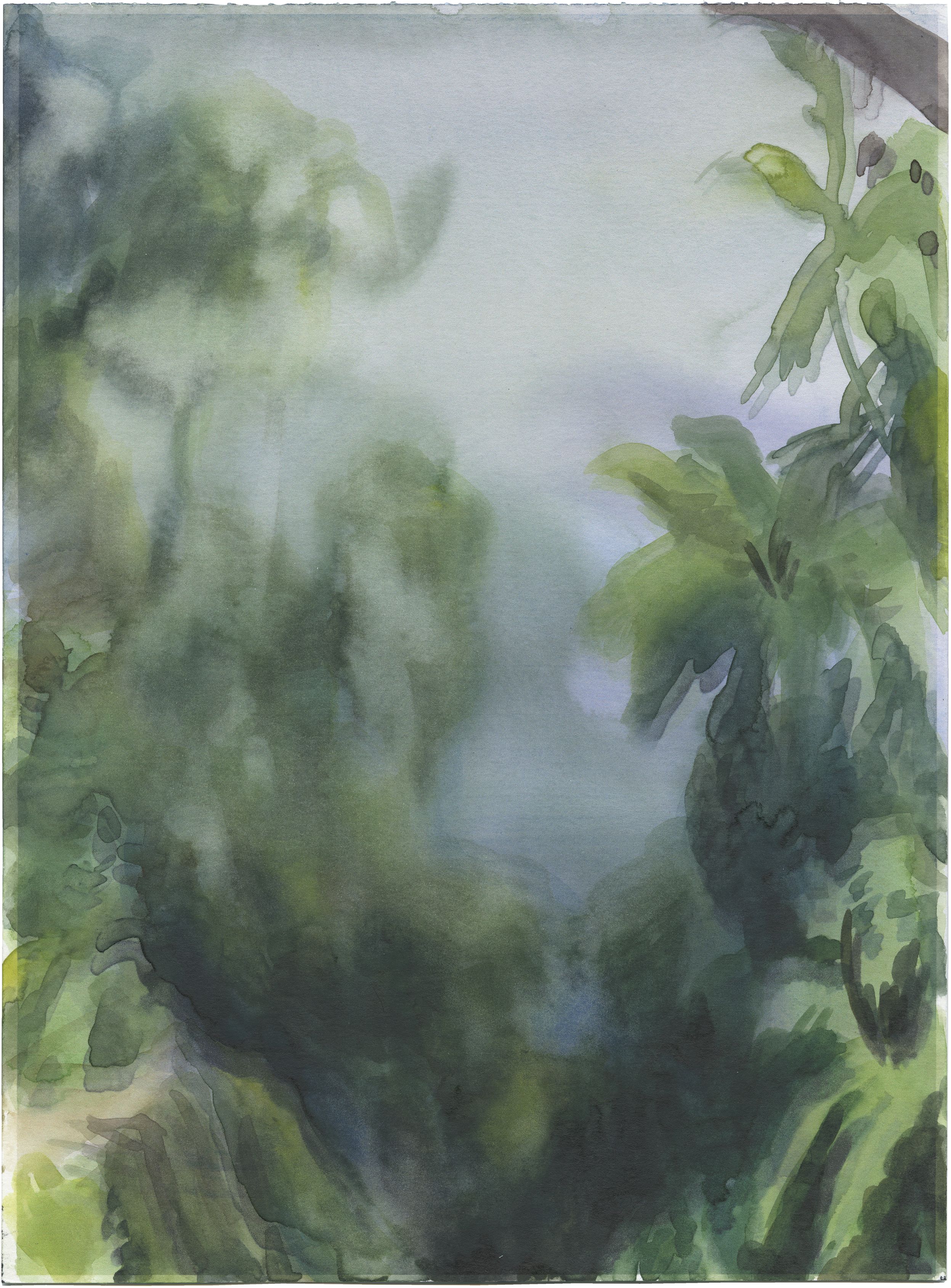

In 'Ins and Outs', the curved black lines of a MacBook screen divide the compositions into seemingly disparate spaces. Doors and windows create moments of connection between the cartoon environments and their domestic counterparts, an endless loop of entrances and exits.

Ins and Outs (Fifth Column Mouse), 2024, watercolour on paper, 22 x 19 cm

Ins and Outs (Rabbit's Kin), 2024, watercolour on paper, 22 x 19 cm

Ins and Outs (My Little Duckaroo), 2024, watercolour on paper, 22 x 19 cm

Ins and Outs (Cheese Chasers), 2024, watercolour on paper, 22 x 19 cm

Ins and Outs (Unknown), 2024, watercolour on paper, 22 x 19 cm

011

To-Do

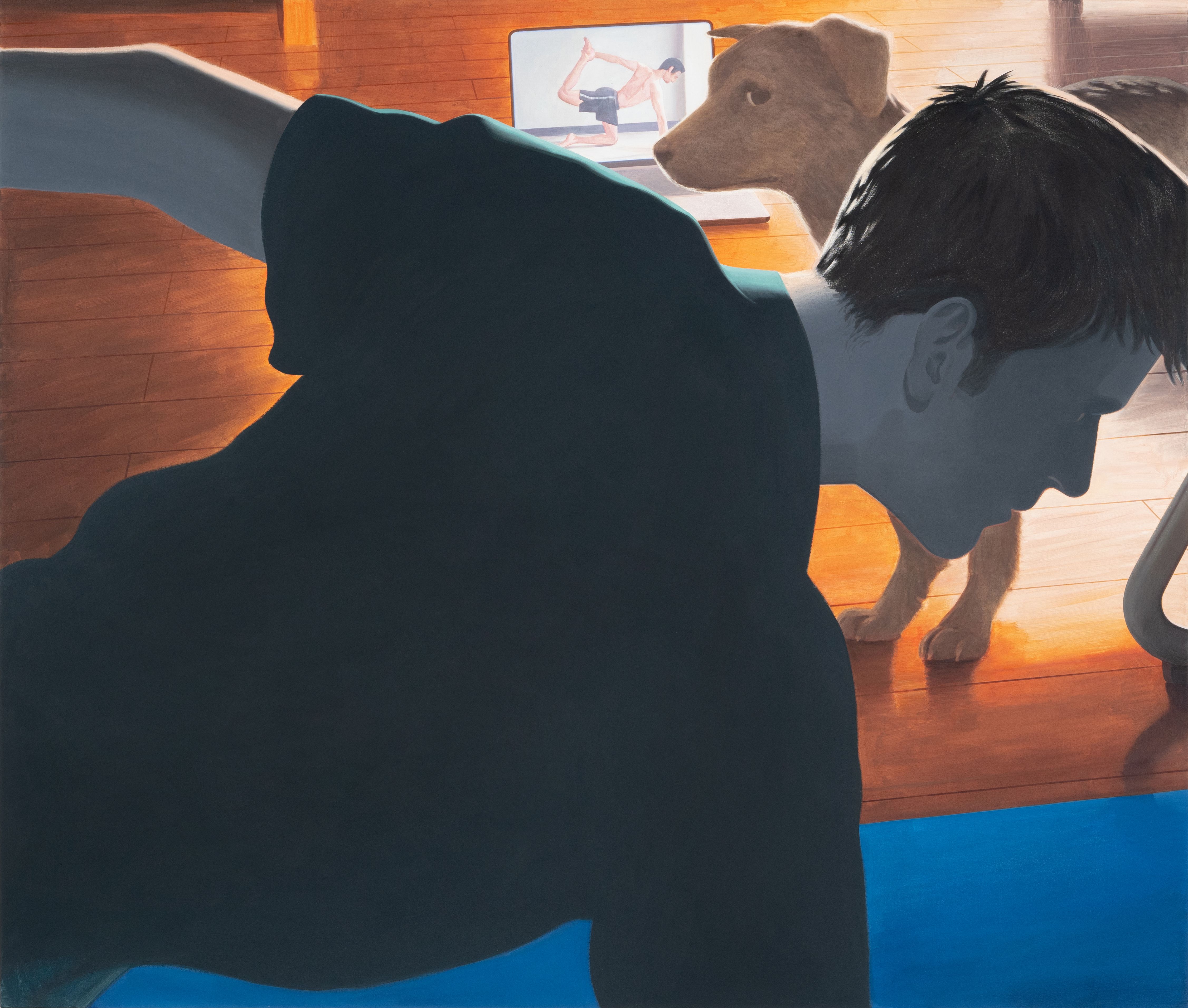

The works on canvas summarized under the title 'To-do' show male figures performing various actions in a domestic environment. Since 2017, I have been collecting my personal to-do lists and recording the noted tasks and duties in drawings. The current paintings in the ongoing series draw on this material. The large-format canvases contrast with the simplicity of the original text specifications. This difference is reinforced by the scale of the motifs and the intensity of the colours.

Yoga II, 2024, acrylic and vinyl on canvas, 170 x 200 cm

Yoga, 2023, acrylic and vinyl on canvas, 170 x 200 cm

Hello, 2023, acrylic and vinyl on canvas, 170 x 200 cm

010

Moody Layouts

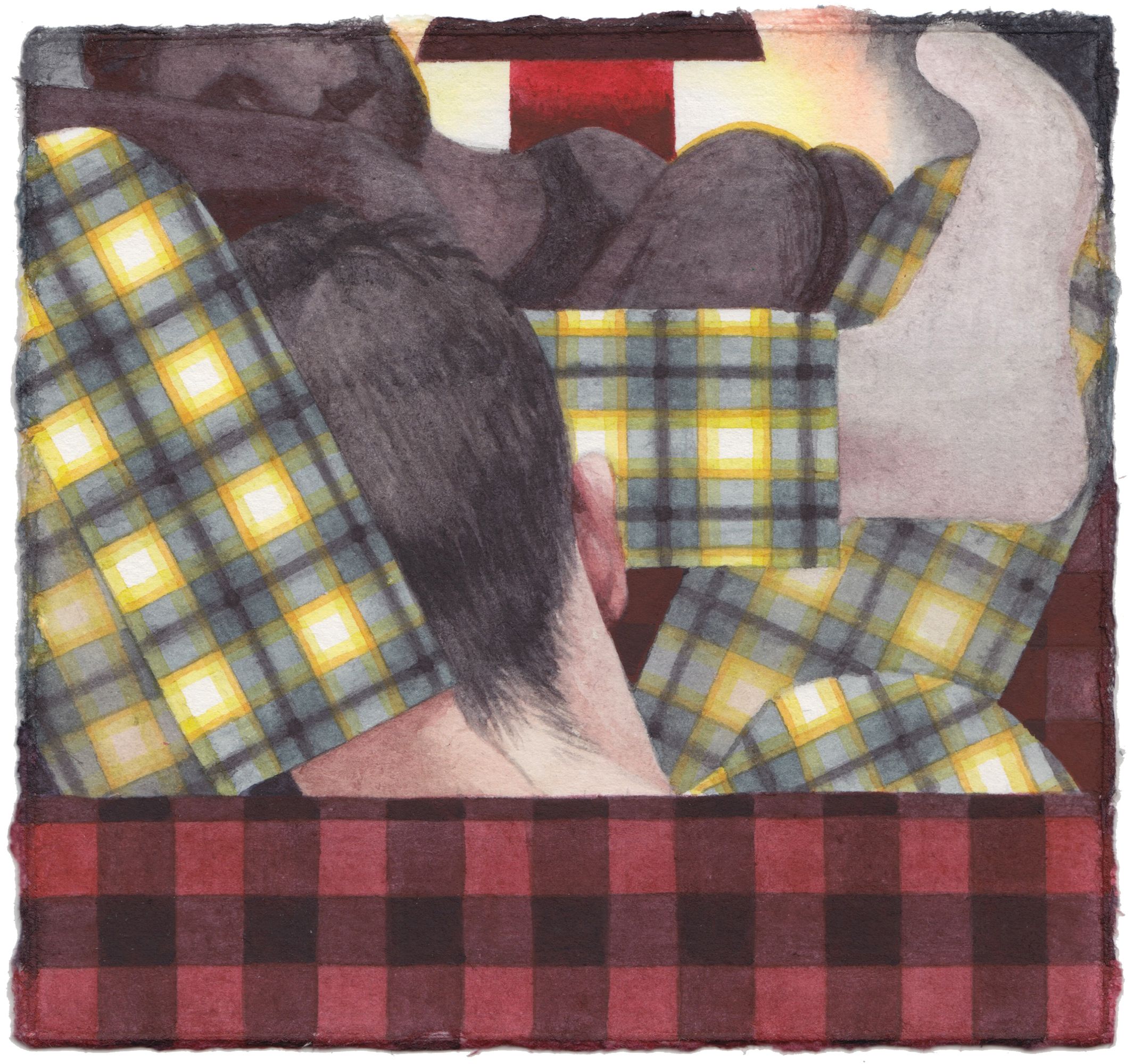

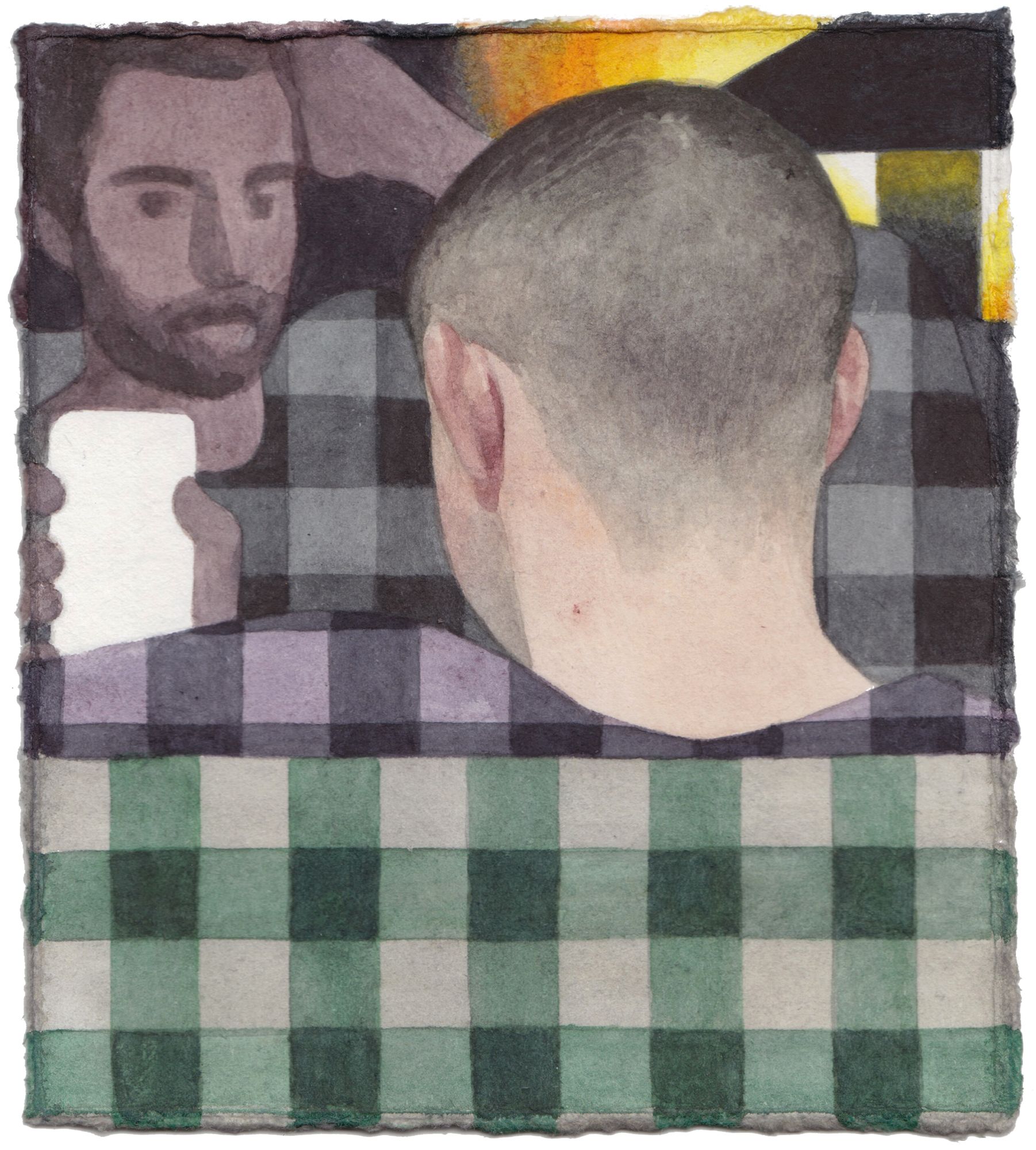

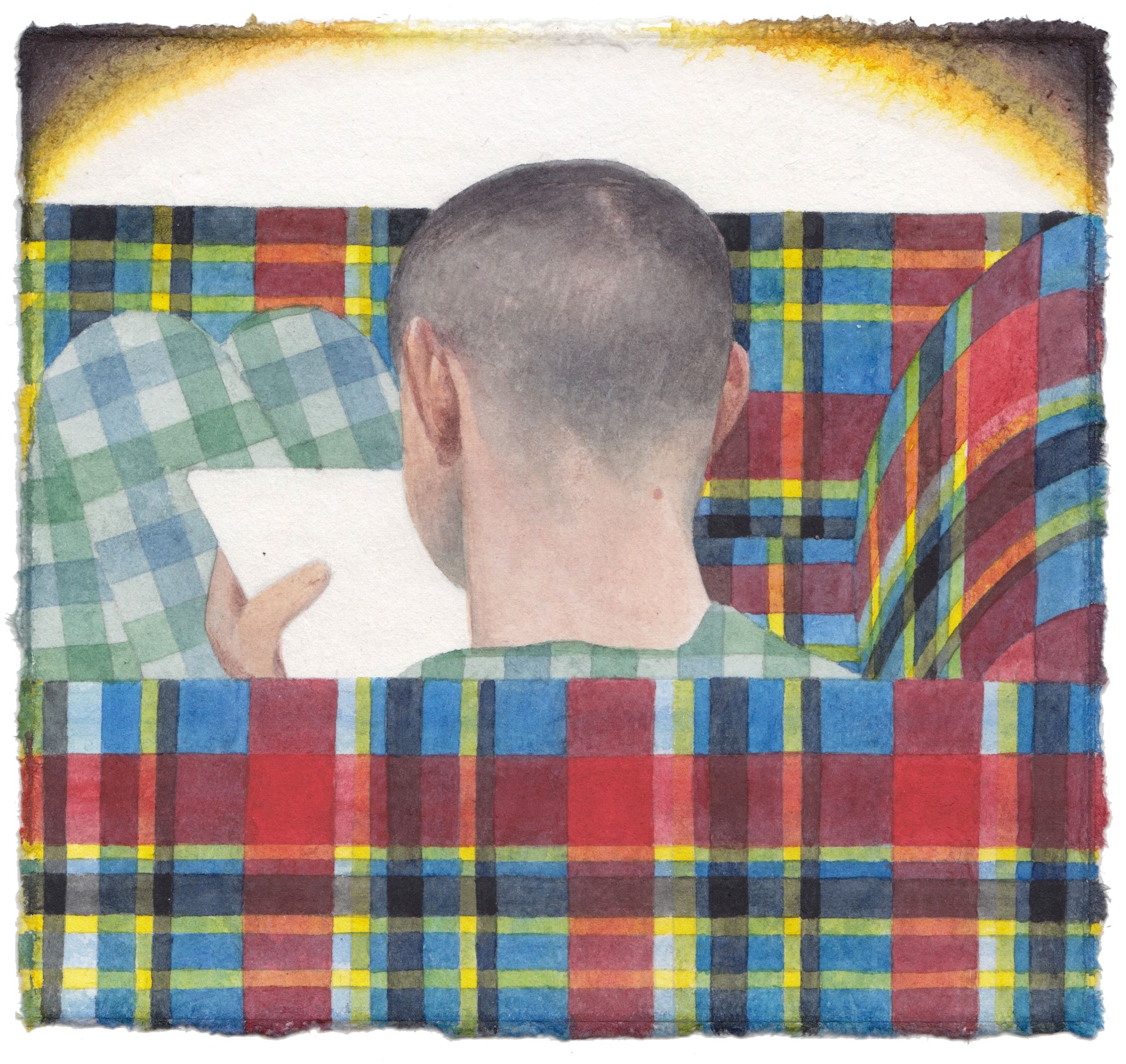

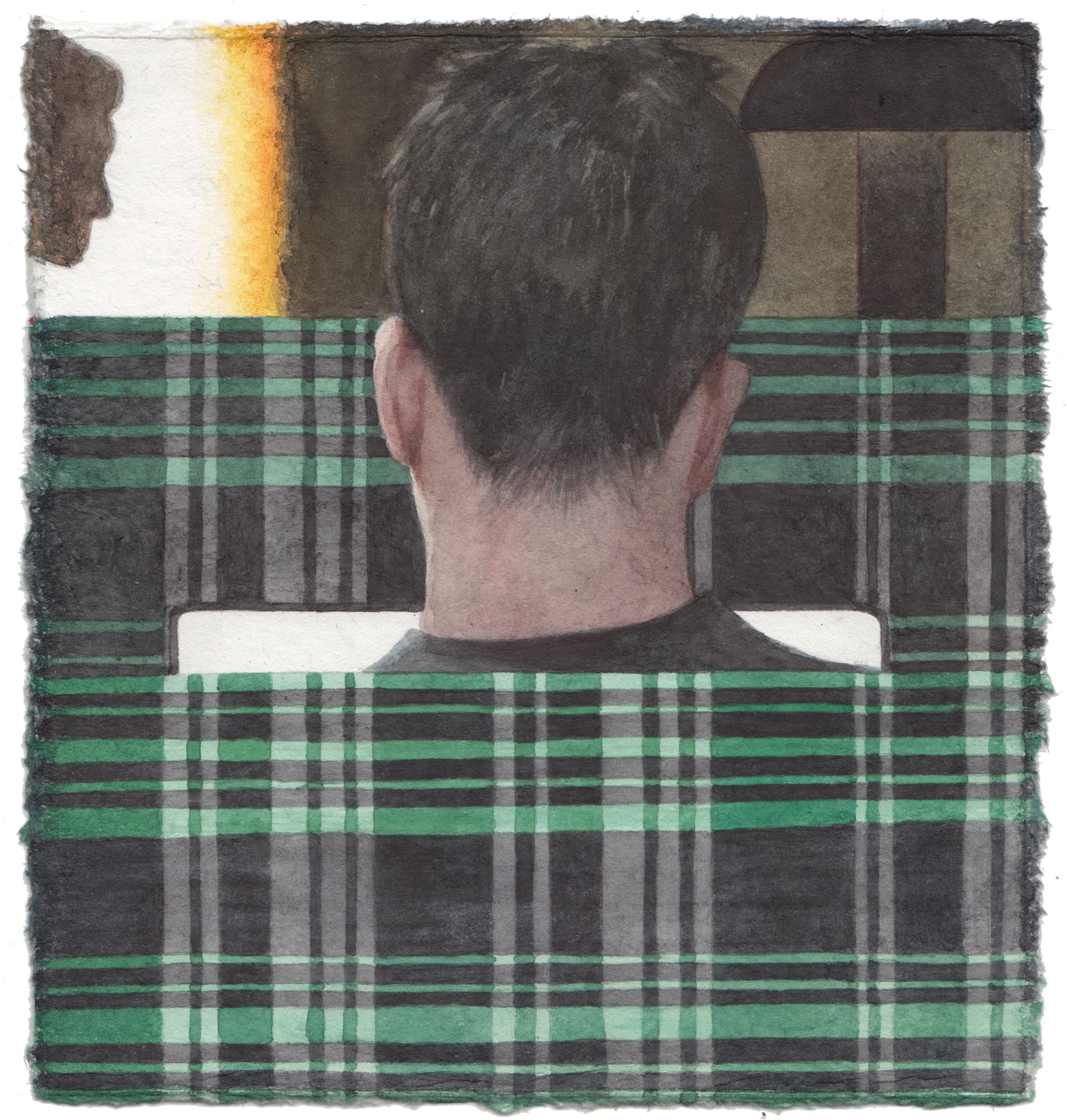

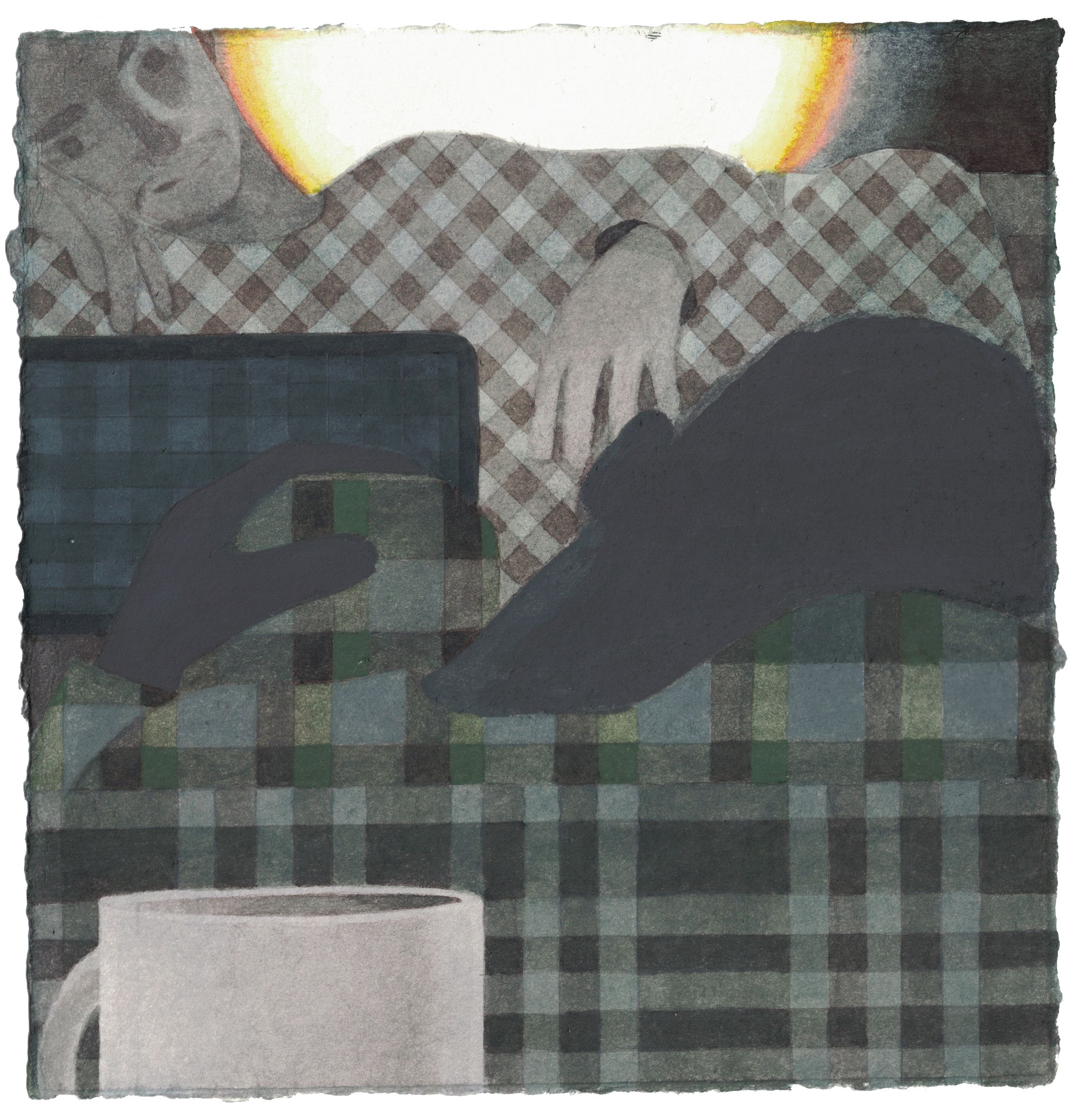

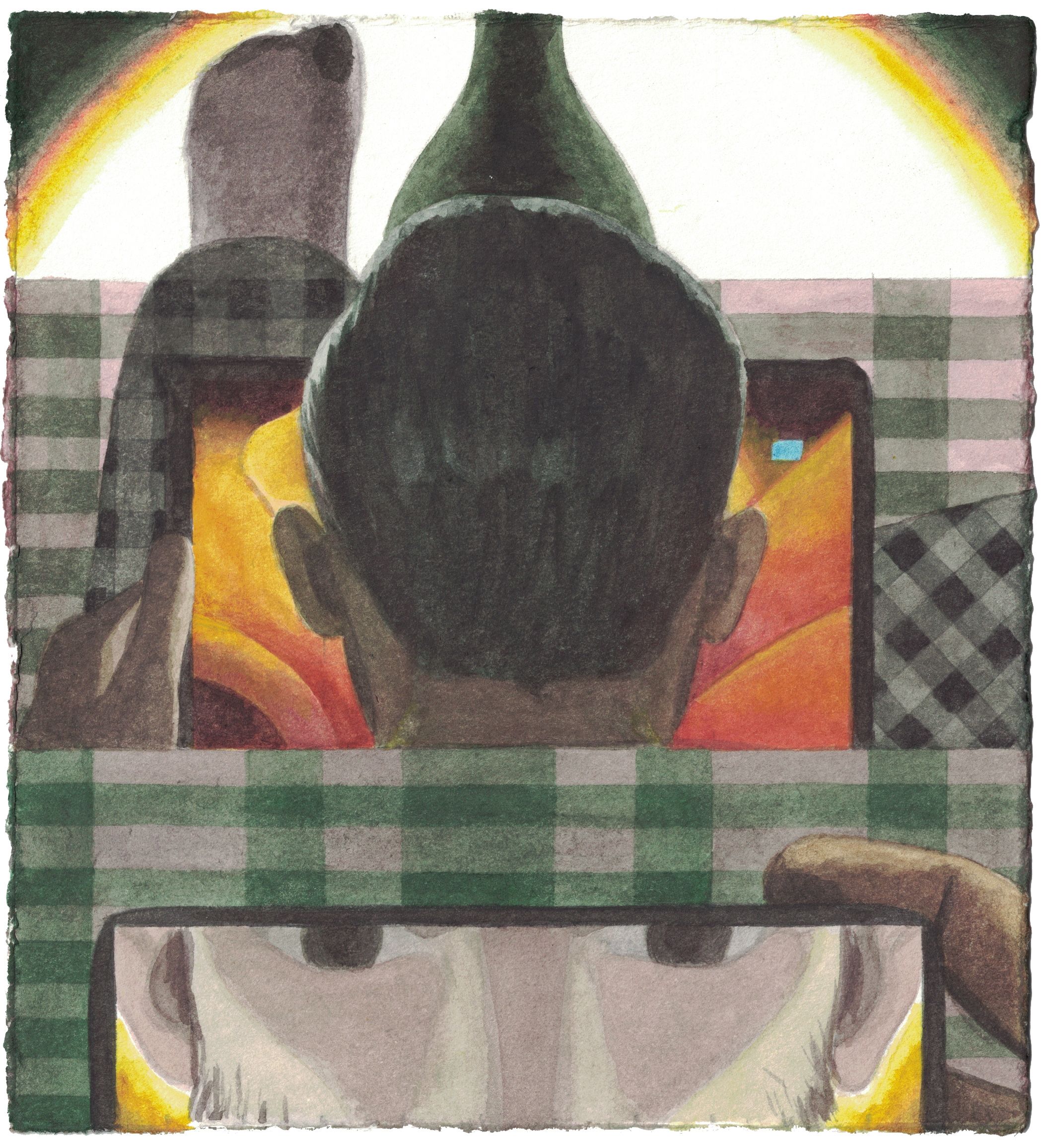

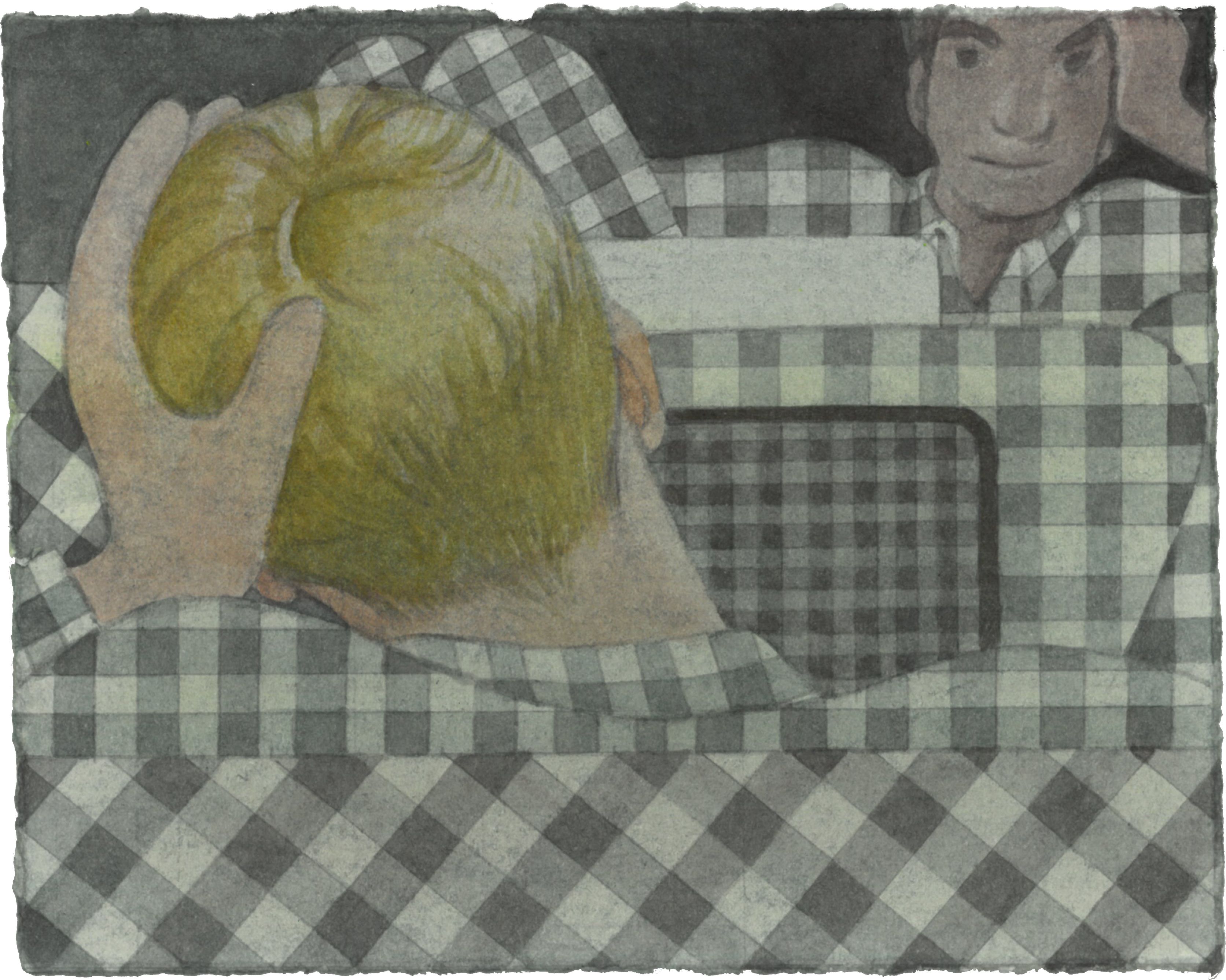

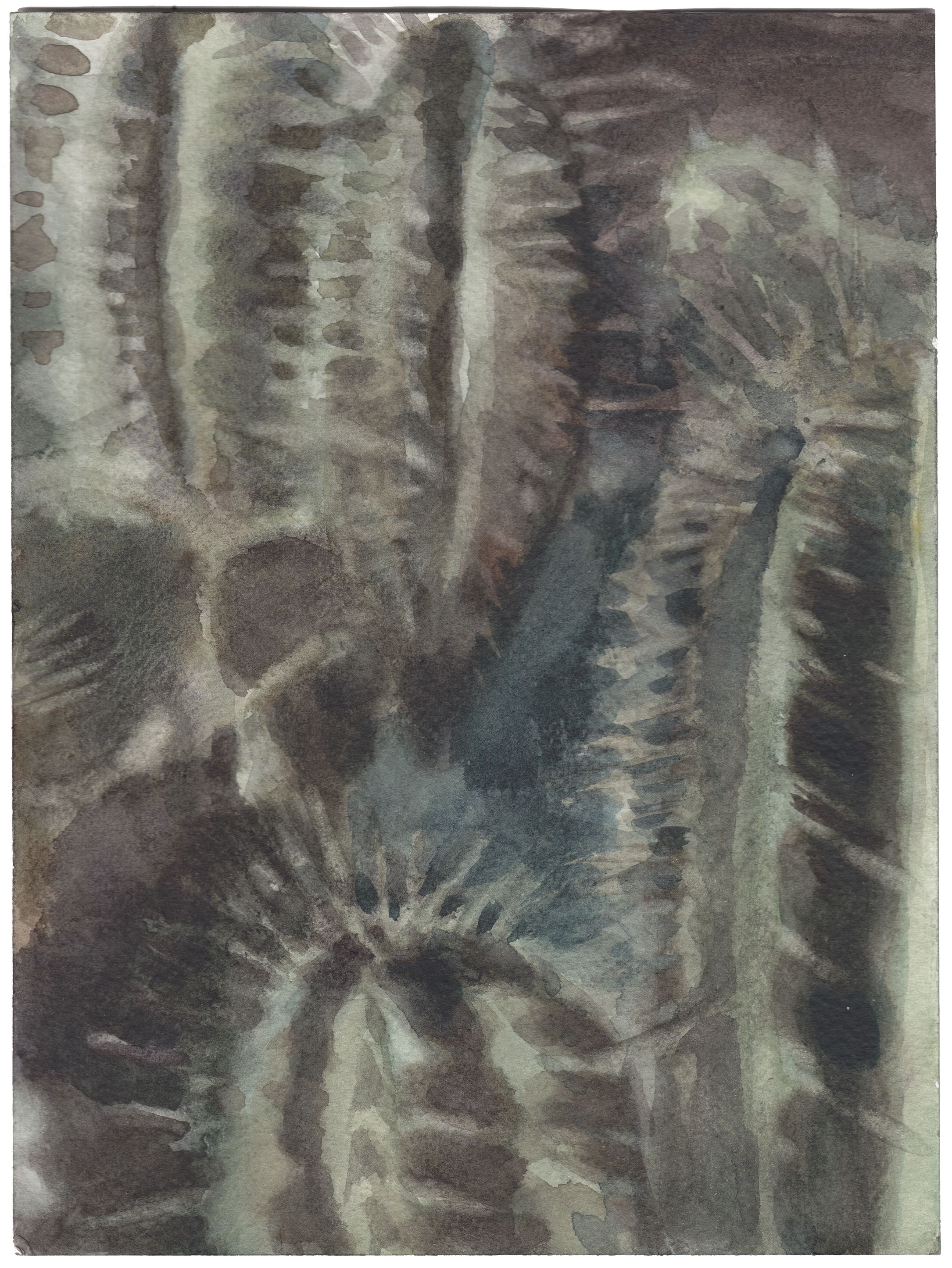

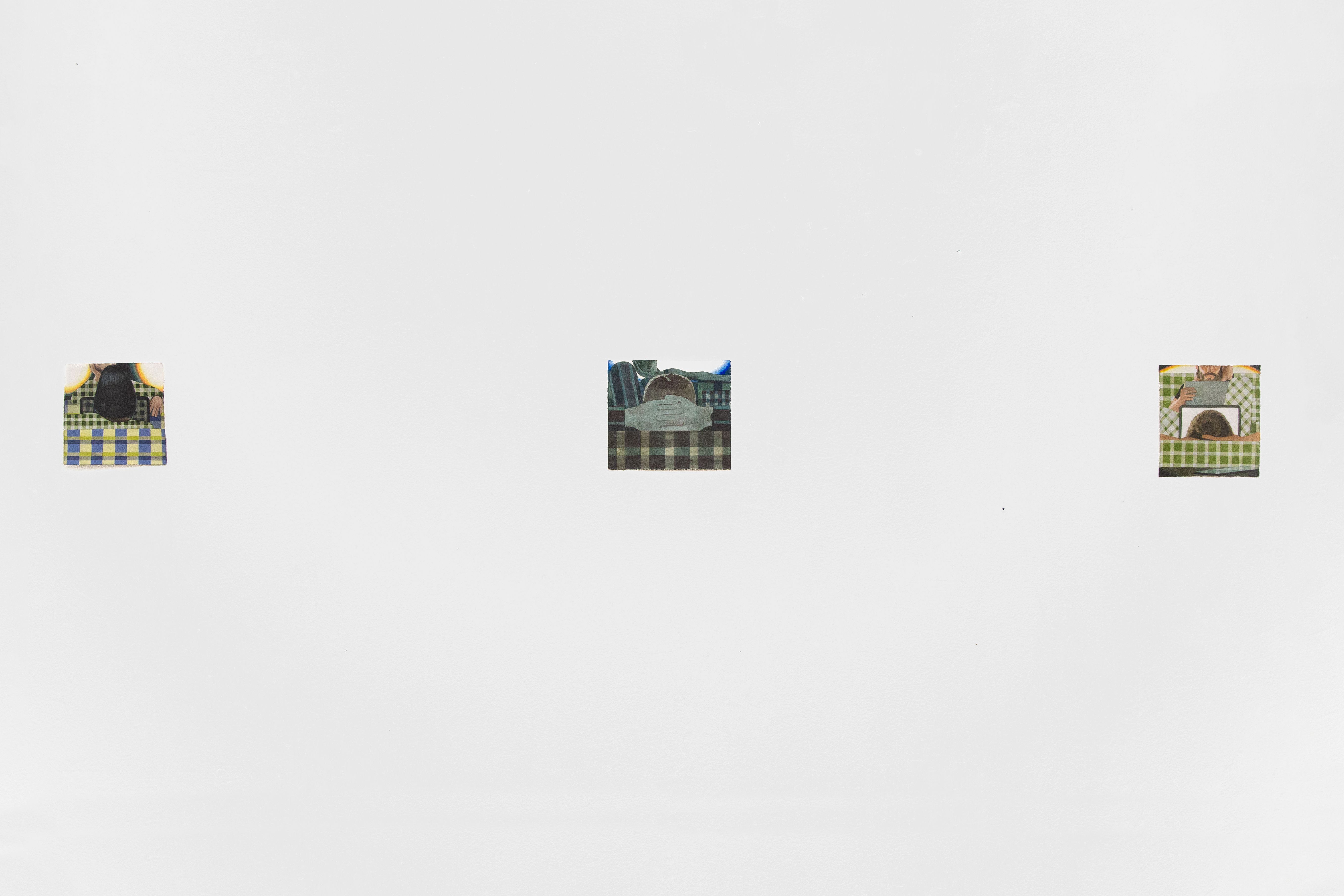

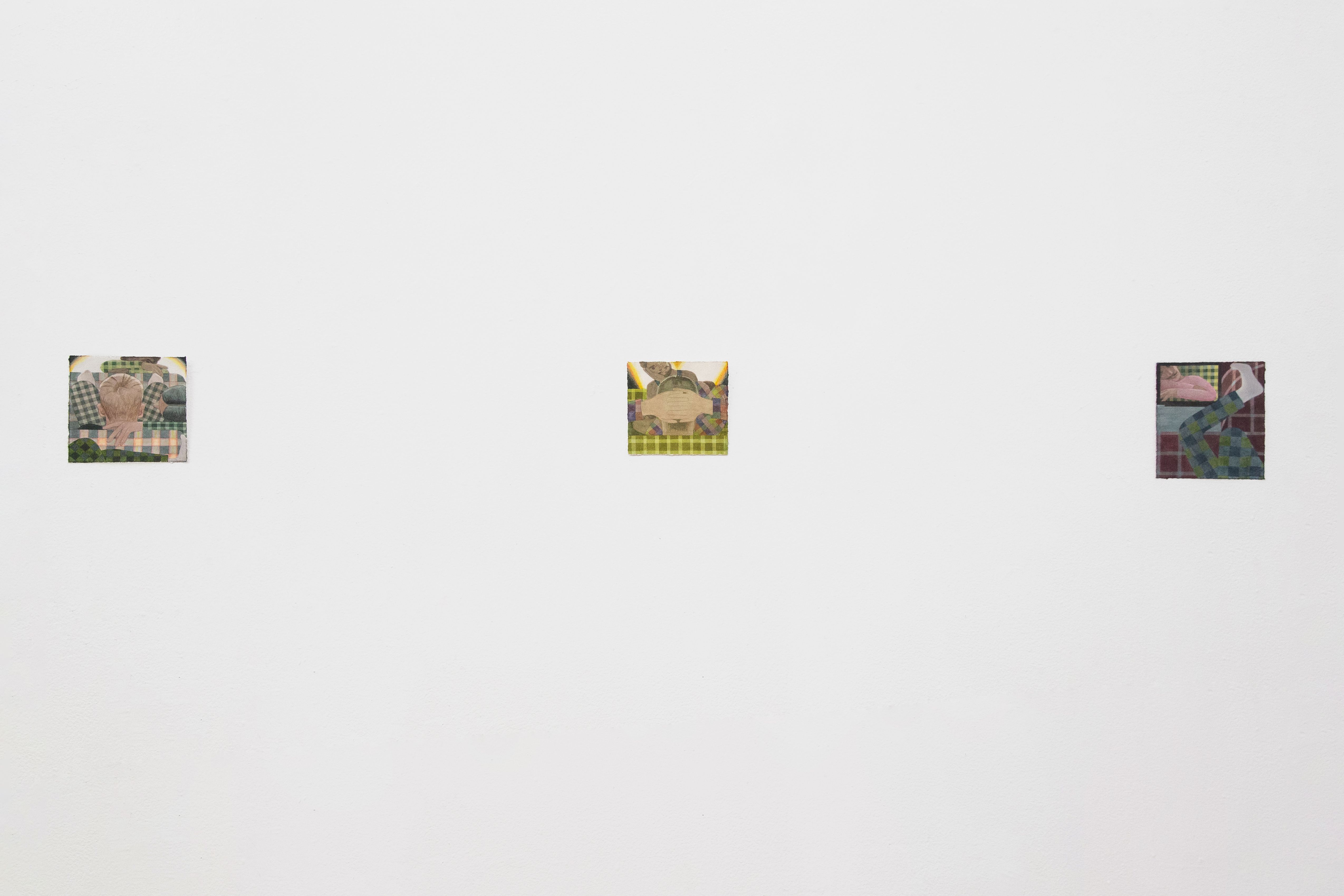

The interiors in 'Moody Layouts' are filled with figures, objects and patterns. When not bathed in warm lamplight, the scenes glow in the light of various screens. Patterned pyjamas allow the bodies of the male protagonists to merge with each other and with the surrounding sofa cushions. The watercolours are small and densely painted, requiring a close-up viewing. By carefully tearing the paper, I have exposed the soft fibres at its edges in order to emphasize the work‘s materiality.

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 12 × 13 cm

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 12.5 × 11 cm

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 14 × 15 cm

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 15 × 14 cm

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 13 × 15 cm

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 14 × 14 cm

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 13 × 15 cm

Untitled, 2024, watercolour on paper, 14 × 15 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 11 × 12 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 13,5 × 15 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 14 × 13,5 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 14 × 13 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 14 × 13 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 12 × 13 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 14 × 13,5 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 11 × 14 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 12,5 × 13 cm

Untitled, 2023, watercolour on paper, 17 × 13 cm

009

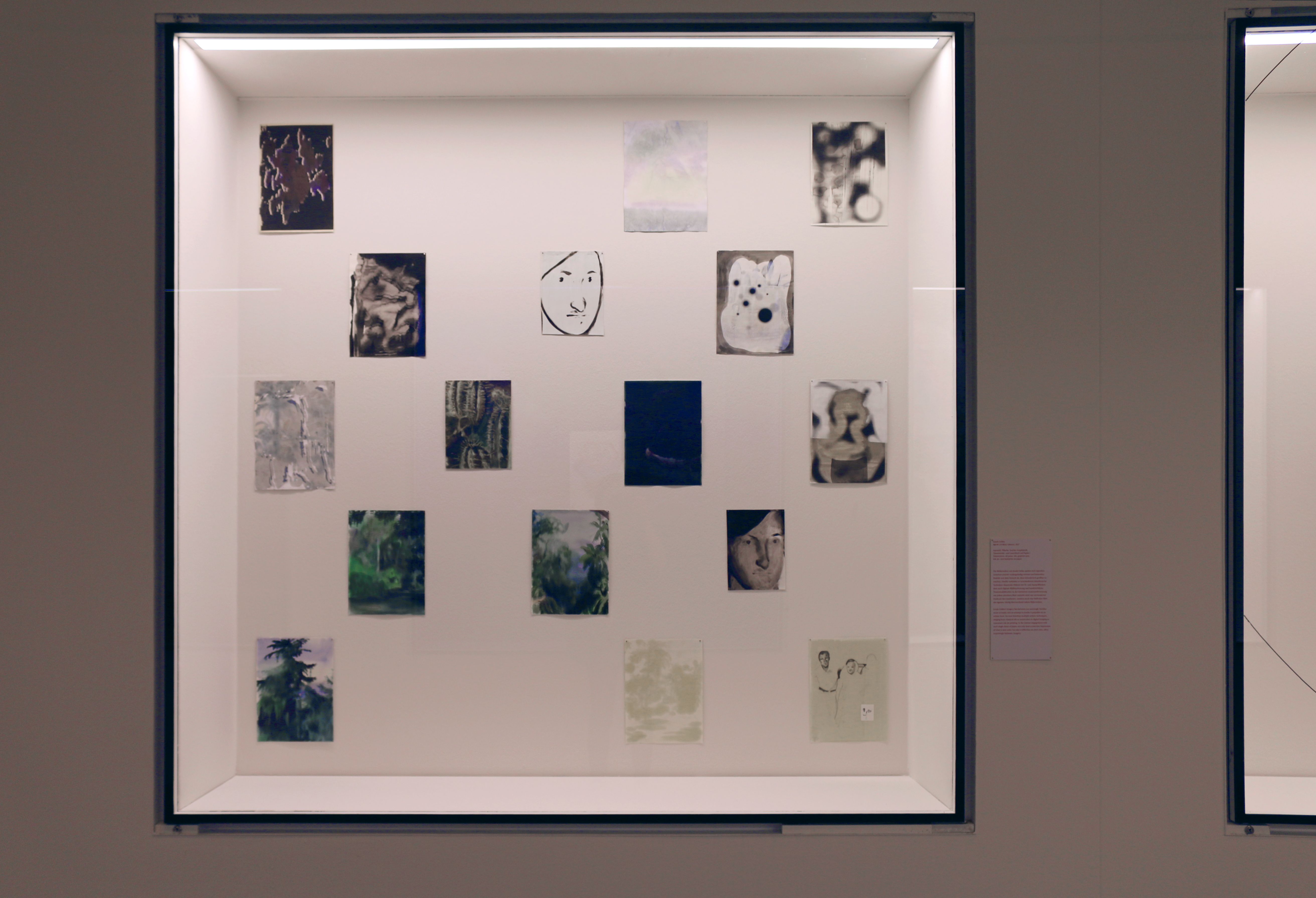

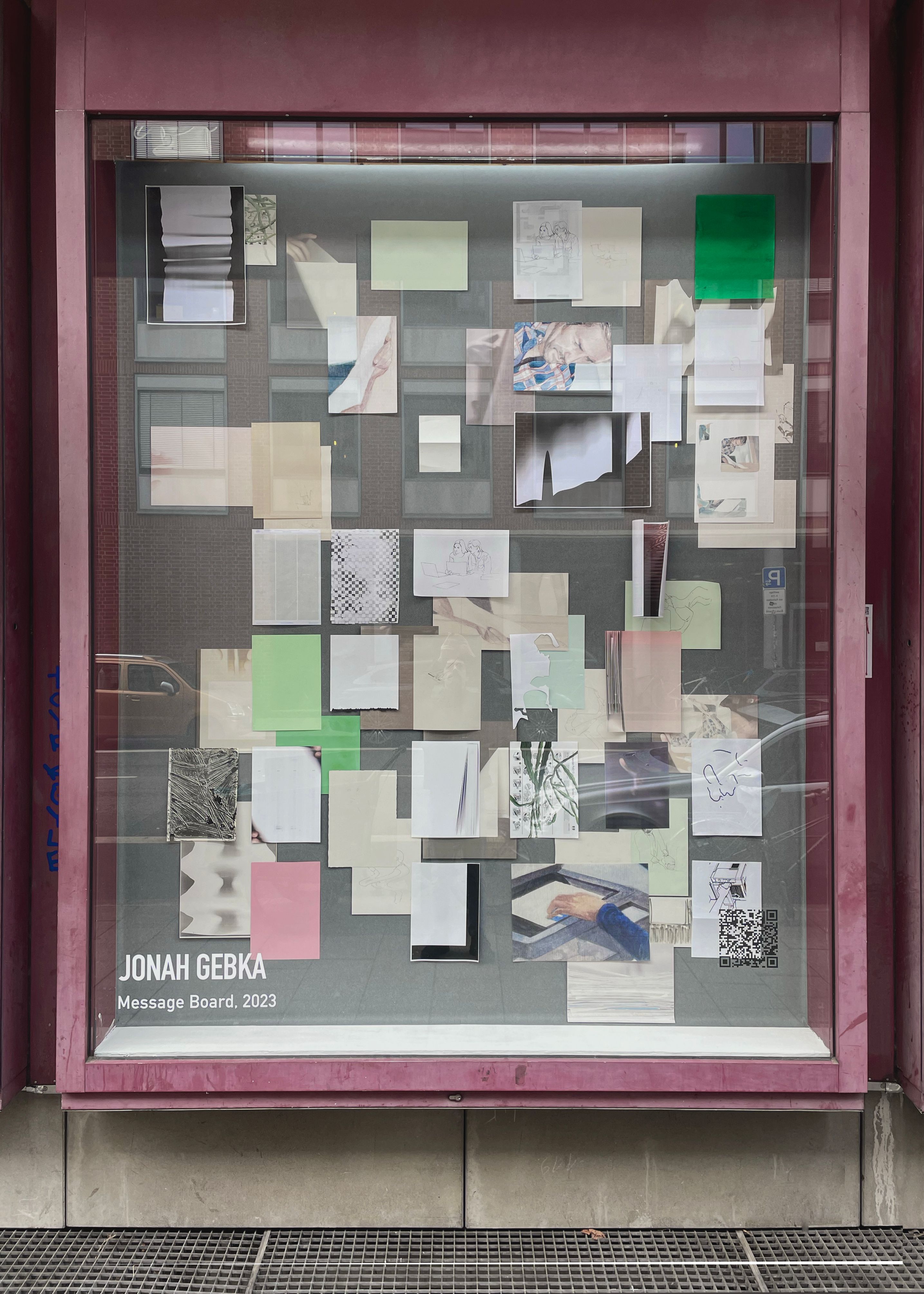

Message Board

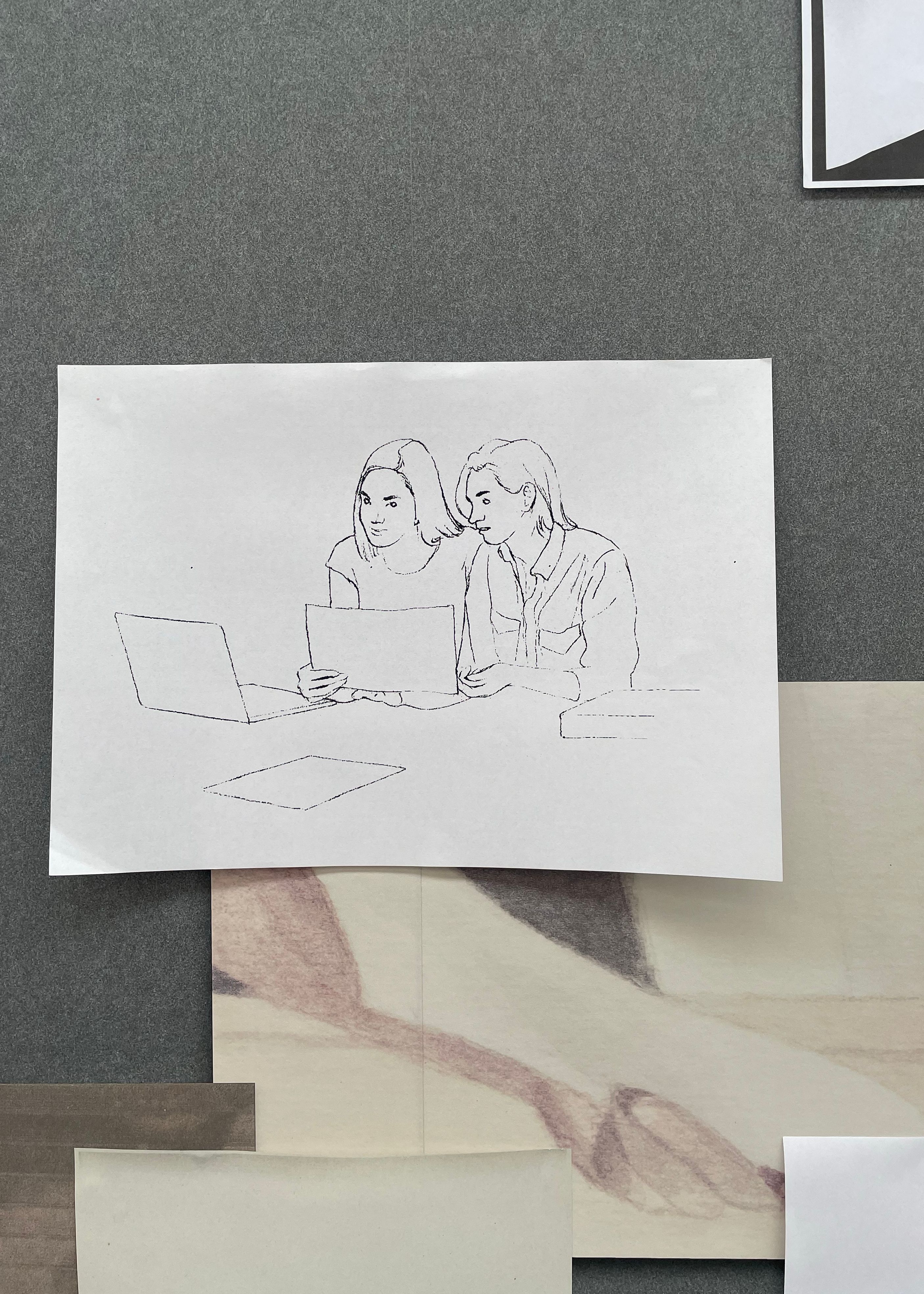

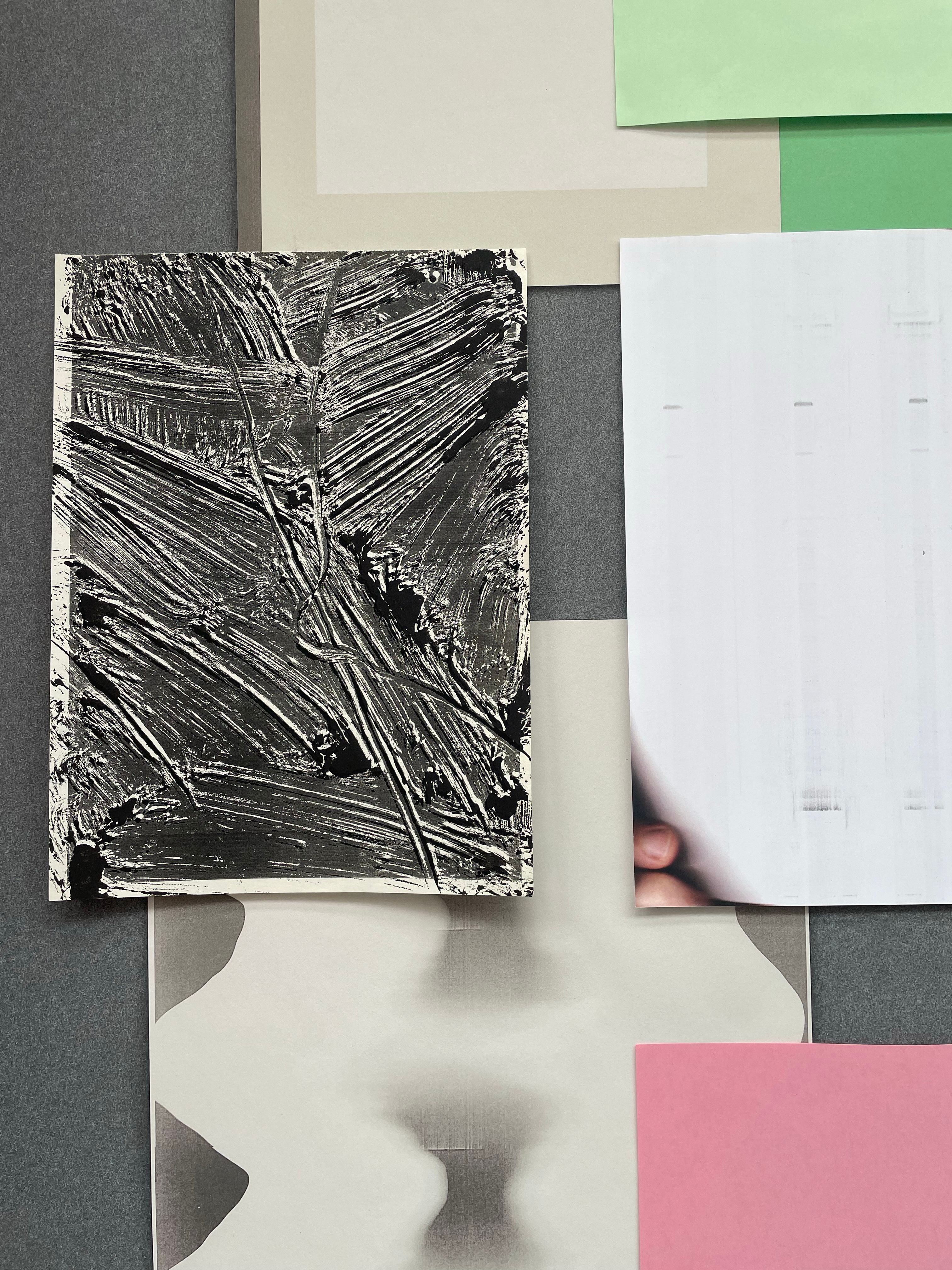

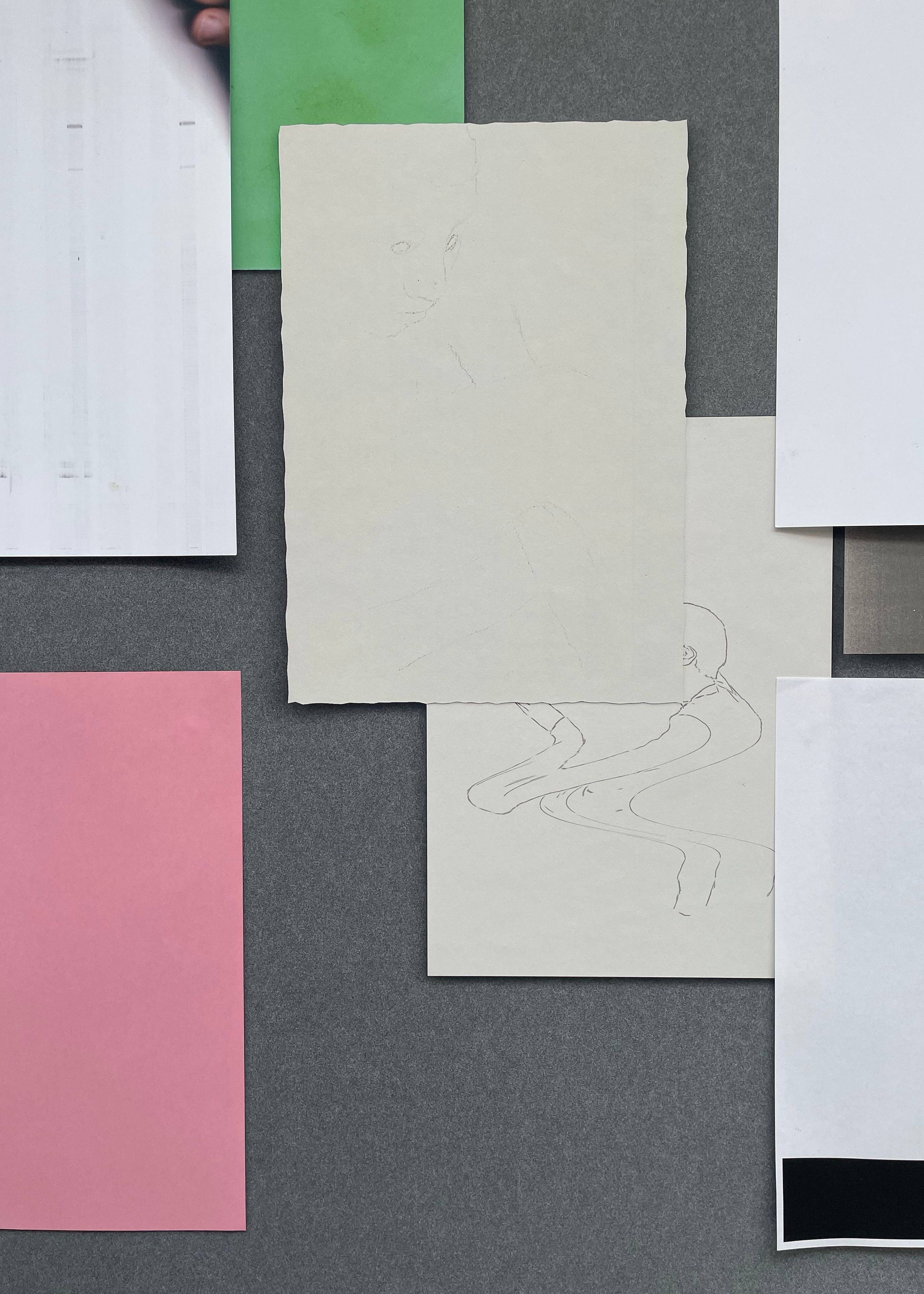

'Message Board' was designed for a window display at the Lost Weekend Café in Munich. I was inspired by the bulletin boards of the nearby university buildings. The installation consists of a large-format wallpaper print on which 16 works on paper are mounted. By using 3D rendering programs, the print was designed to imitate and illusionistically extend the light situation in the shop window and the works on paper presented. This visual effect aims to blur the distinction between printed and tangible objects. Real and printed shadows overlap, motifs repeatedly appear.

Message Board, 2023, 260 x 210 cm (installation view)

Message Board, 2023, 260 x 210 cm (detail view)

Book

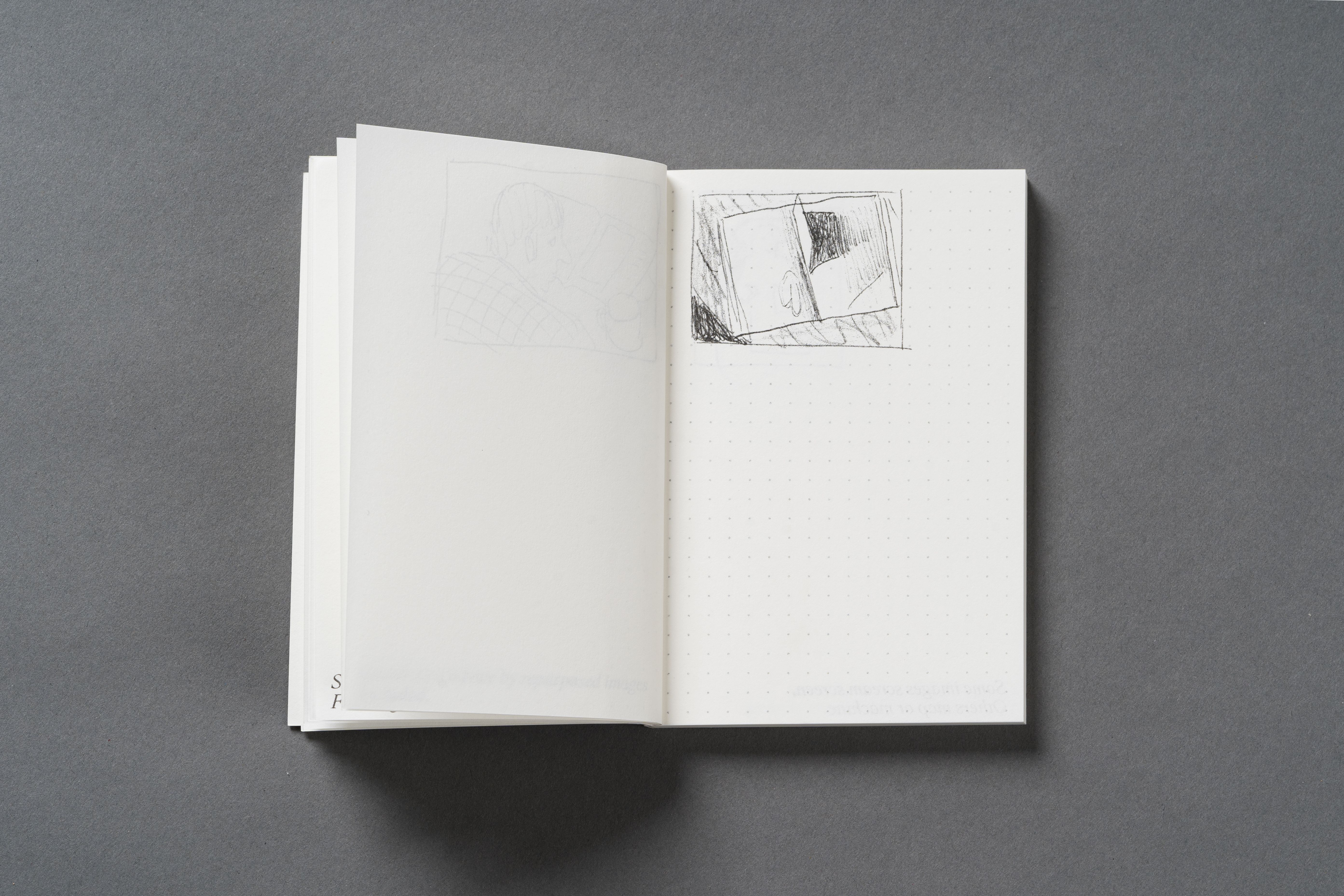

Browser

The pocket sized booklet combines drawings and texts produced in the months leading up to the exhibition 'Blue Light' at Boutwell Schabrowsky in Munich. 'Browser' mines unused scribbles for future paintings, repurposed quotes, and notes from several sketchbooks to reflect on the shortcomings of language as well as the many hats images wear. Recurring characters are a missing cat, an open book, and question marks. The booklet's cover is embossed and the pages are printed on a risograph machine by Herr & Frau Rio in Munich; it measures 9.5 × 14.5 cm. Artist Giulia Zabarella helped compile the texts, while the design concept was developed in collaboration with Manuel Lorenz. The production of 'Browser' was supported by the Stiftung Kunstfonds.

008

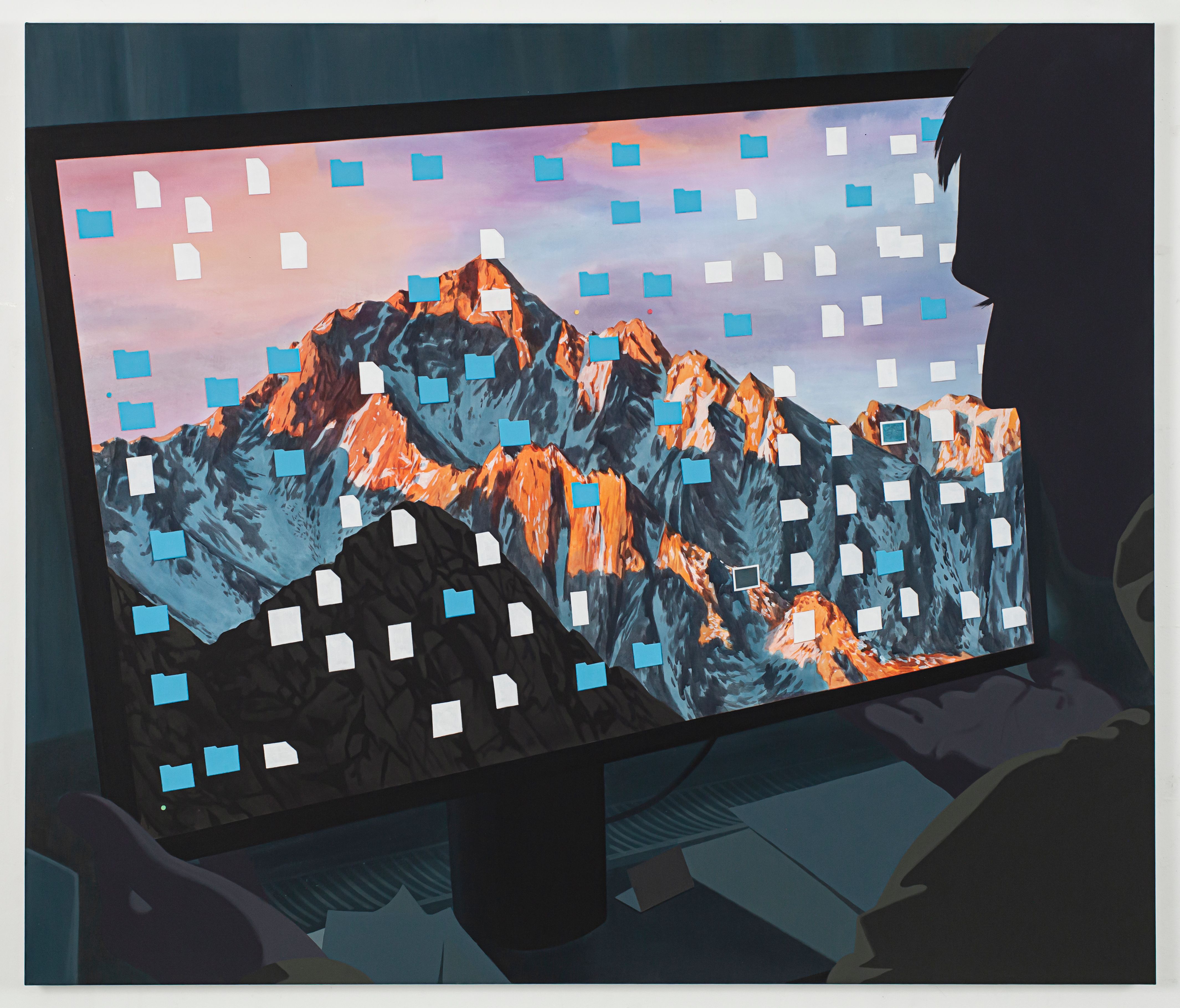

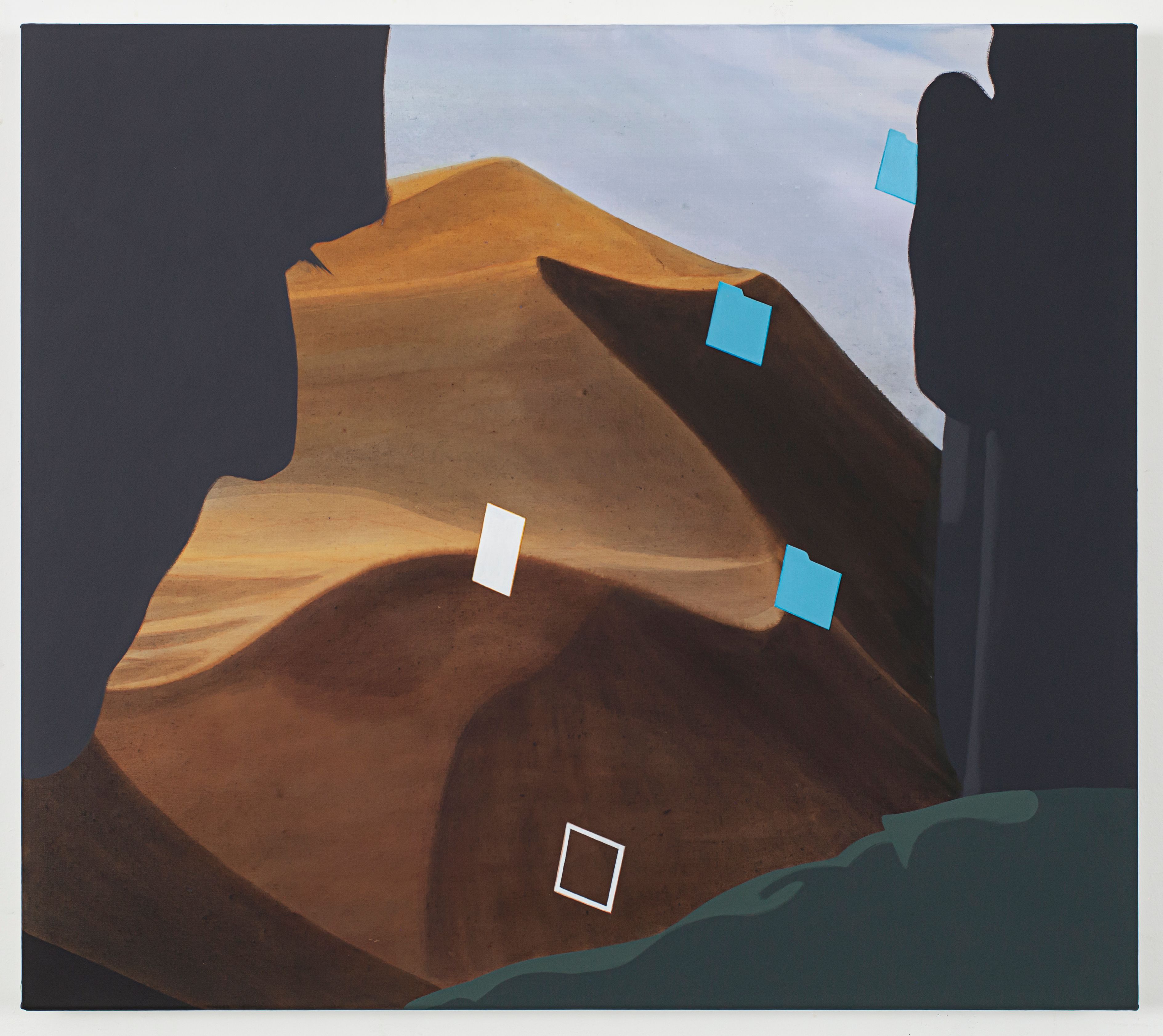

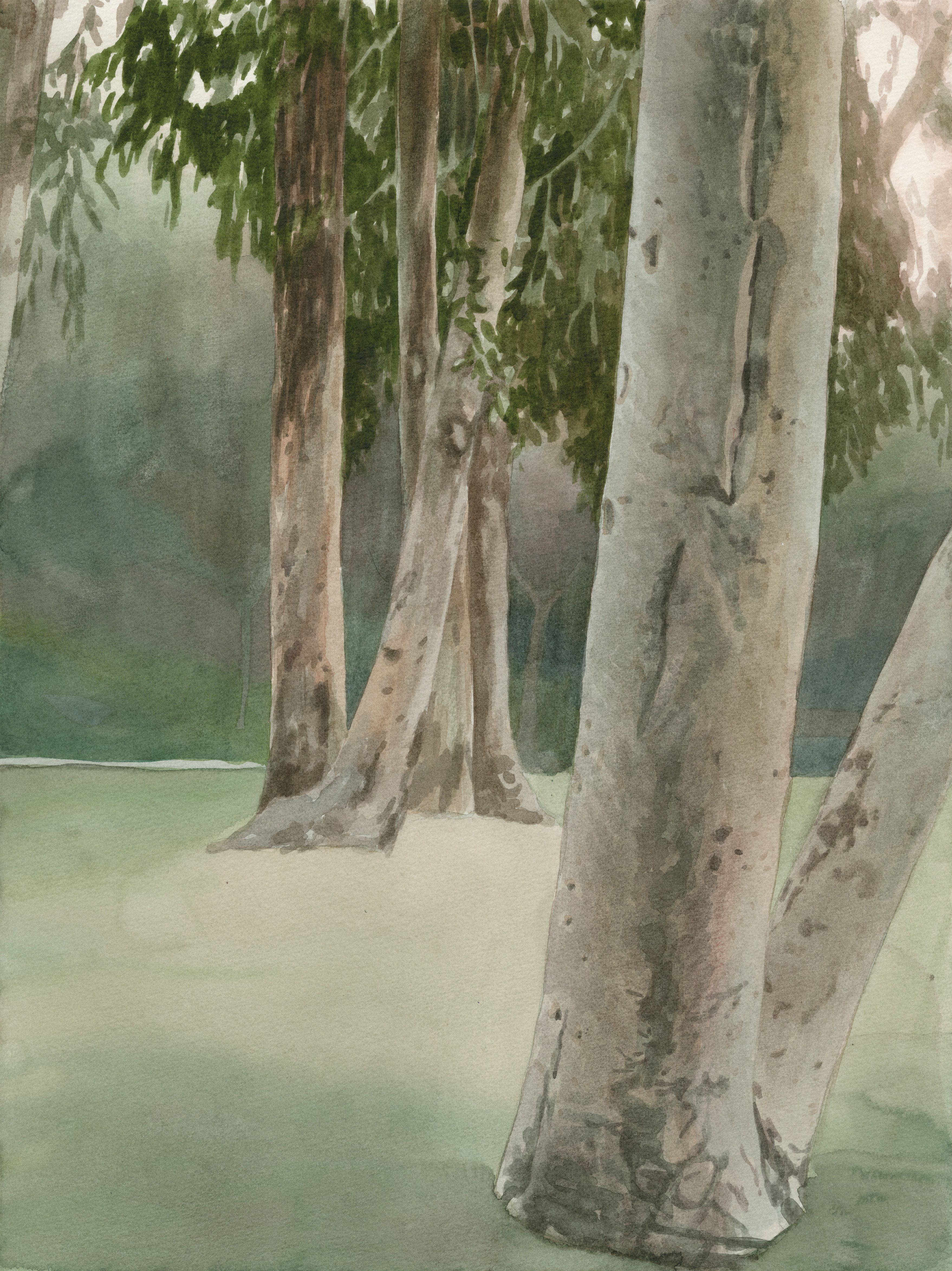

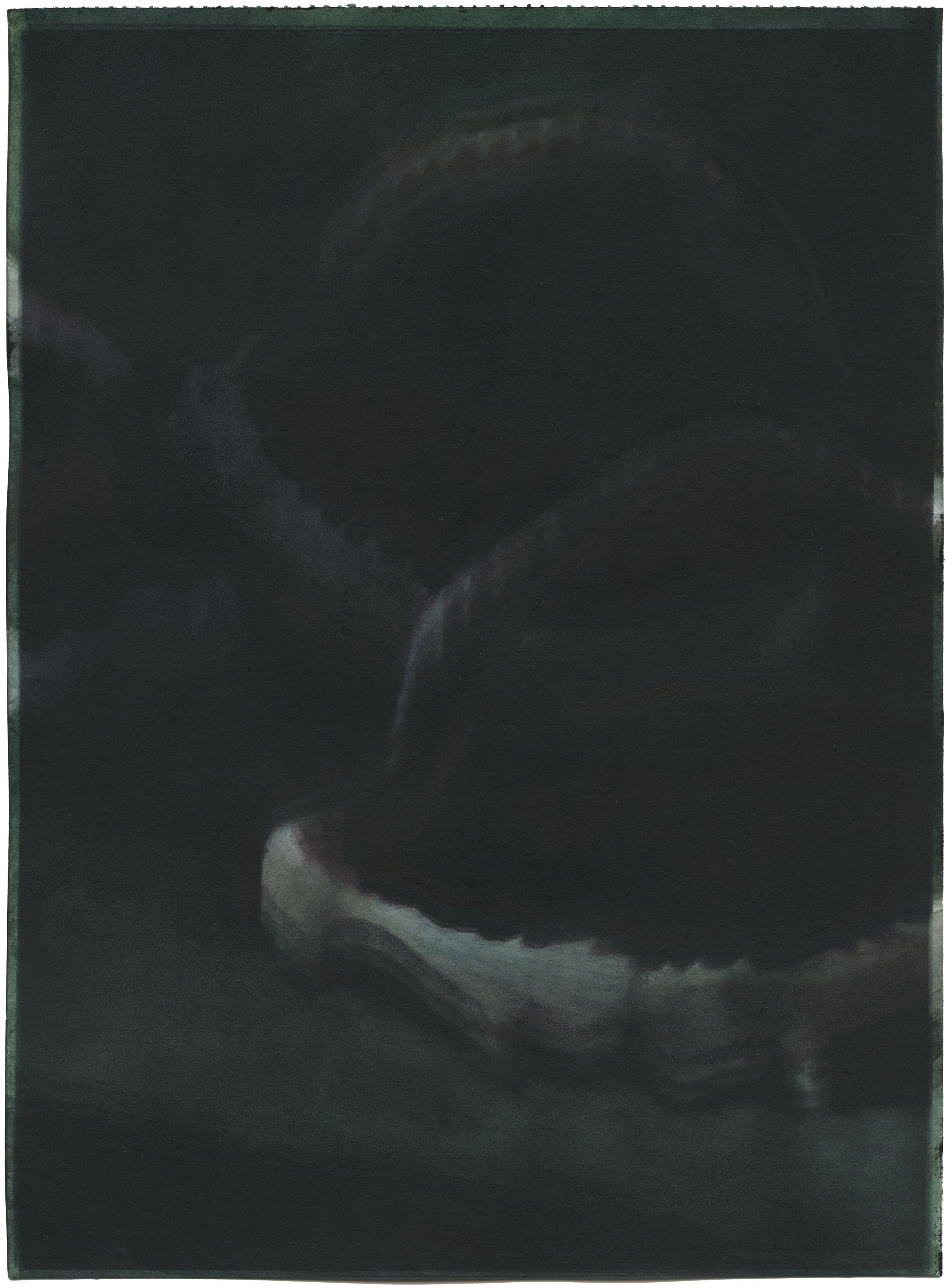

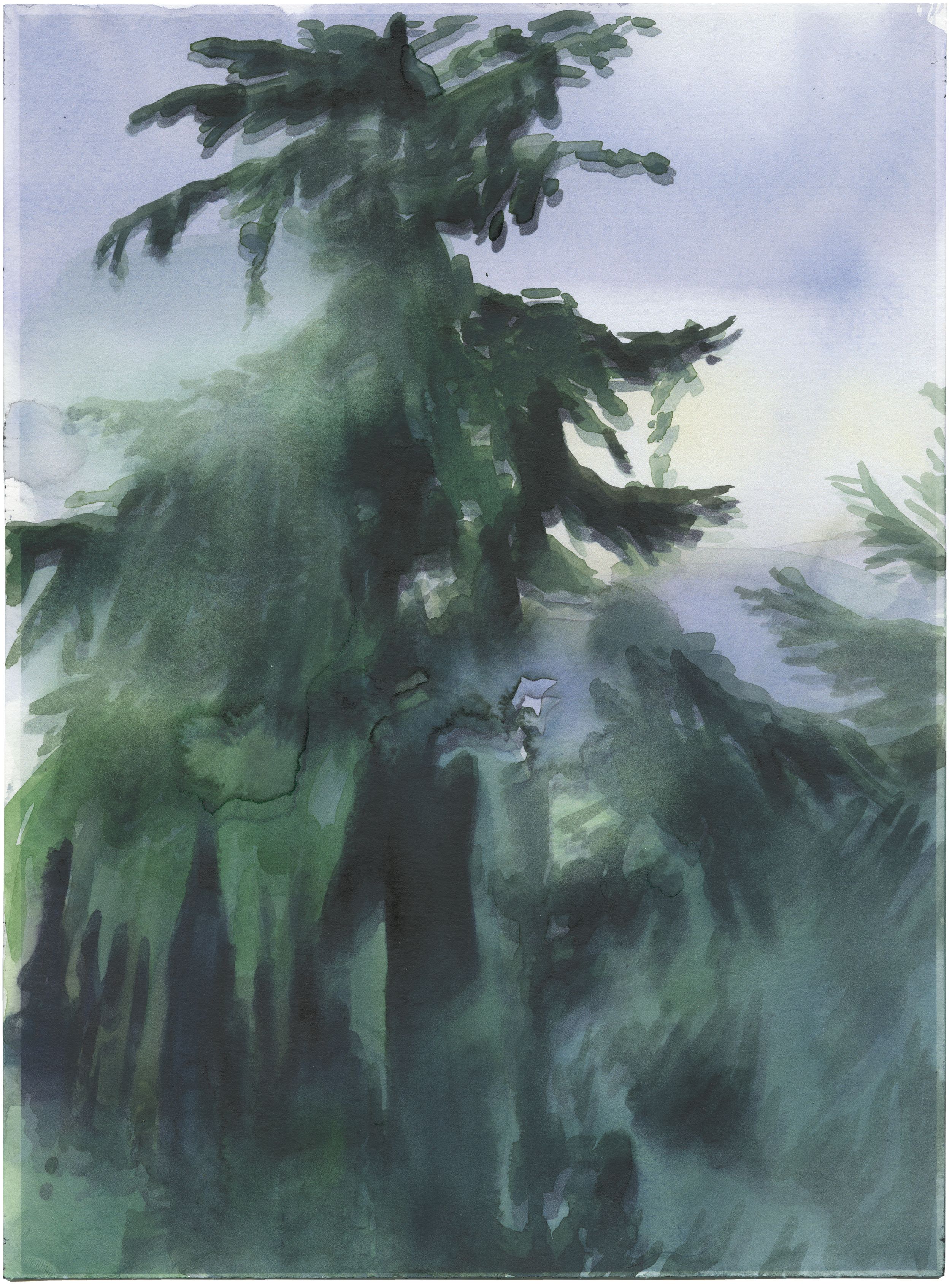

Night Views

'Night Views' shows painted reproductions of wallpaper images from Apple's macOS operating system. The nocturnal scenes in which I have embedded these iconic landscapes appear particularly enlarged due to their strong cropping. What happens in front of the screen - anonymous backs of heads and profiles of faces, bent elbows in checked shirts and pointing hands - appears flat like a silhouette thanks to the use of matt colors. In contrast, the use of watery colors and overlapping layers enhances the depth of the landscapes depicted.

Sequoia Sunrise, 2024, acrylic and flashe on canvas, 100 x 120 cm

Big Sur Sunset, 2024, acrylic and flashe on canvas, 100 x 120 cm

High Sierra, 2024, acrylic and flashe on canvas, 160 x 200 cm

Big Sur Midnight, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 100 × 120 cm

Catalina Sunset, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 120 × 140 cm

Sierra, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 160 × 190 cm

Monterey, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 100 × 120 cm

Mojave Midday, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 80 × 90 cm

Big Sur Midday, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 70 × 80 cm

Lockscreen, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 60 × 70 cm

Mavericks, 2022, gesso and acrylic on canvas, 80 × 100 cm

007

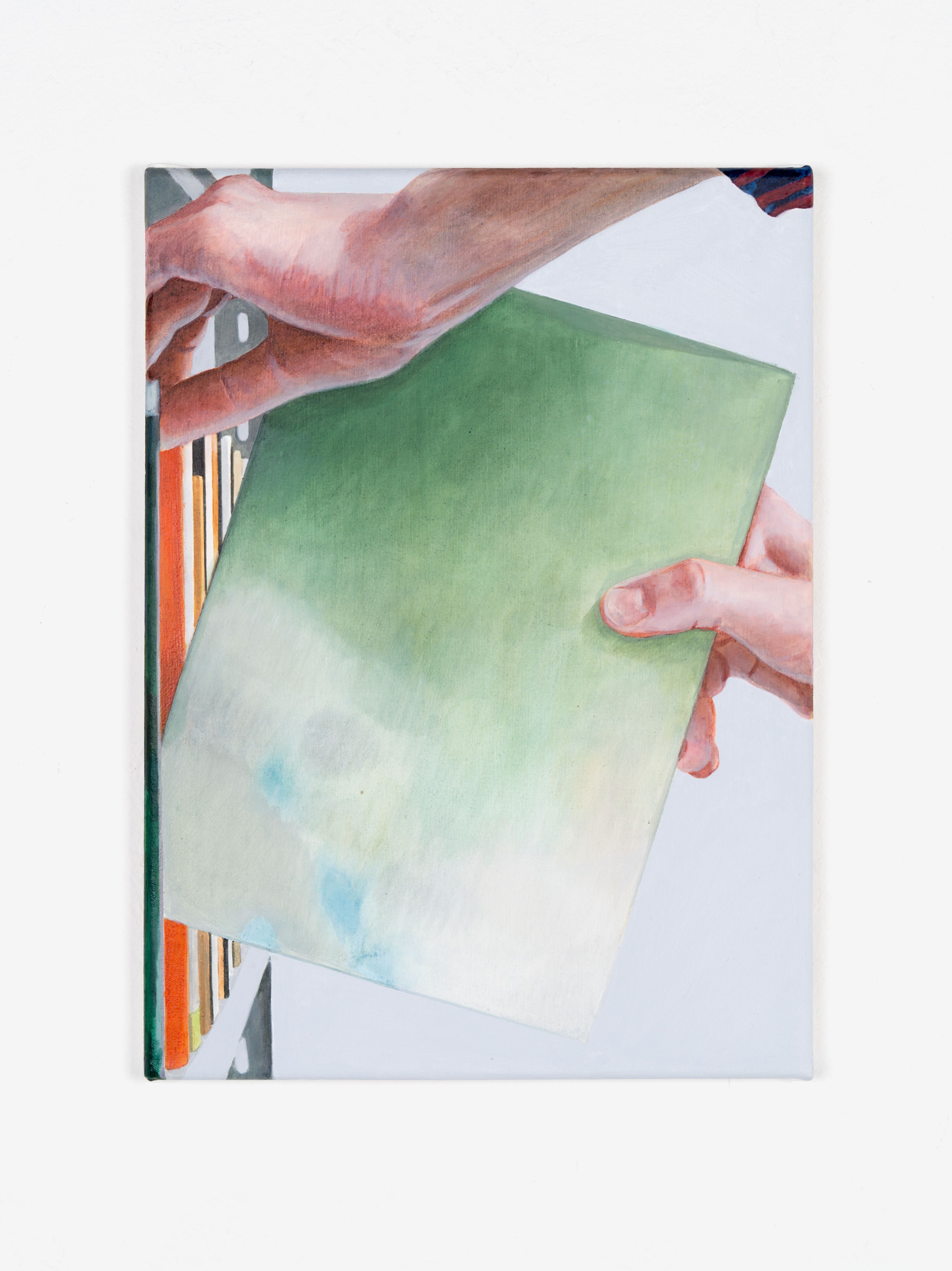

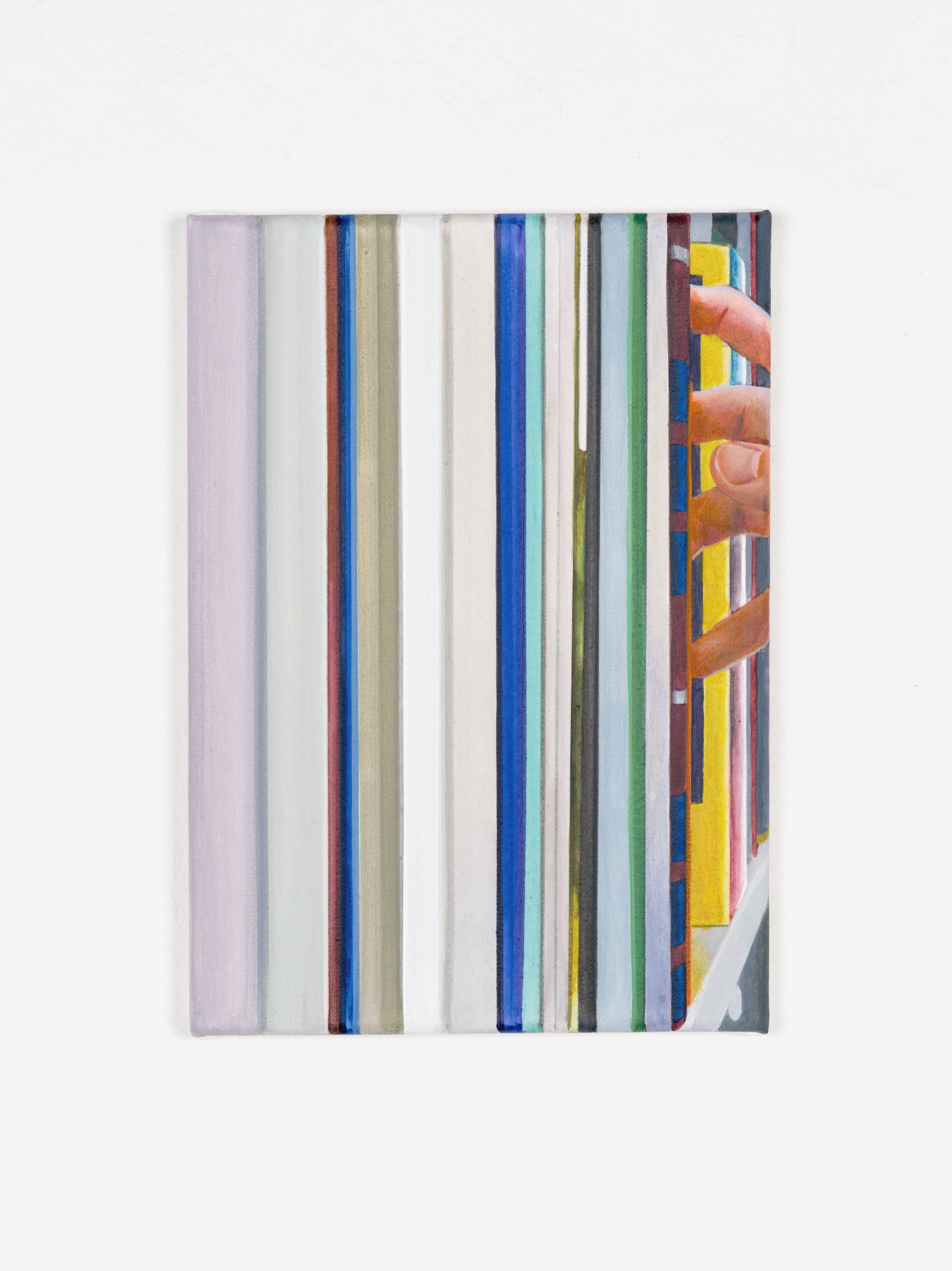

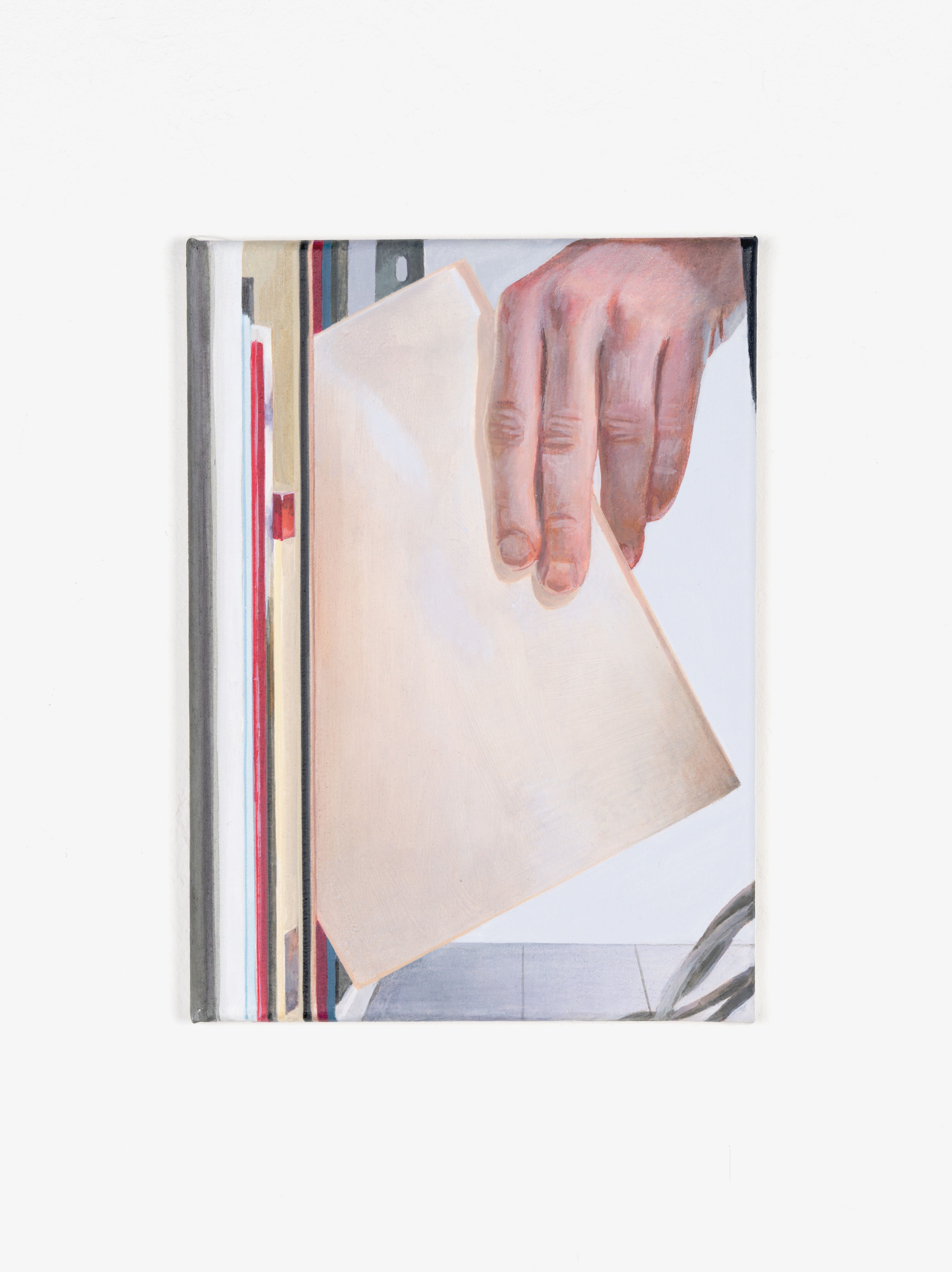

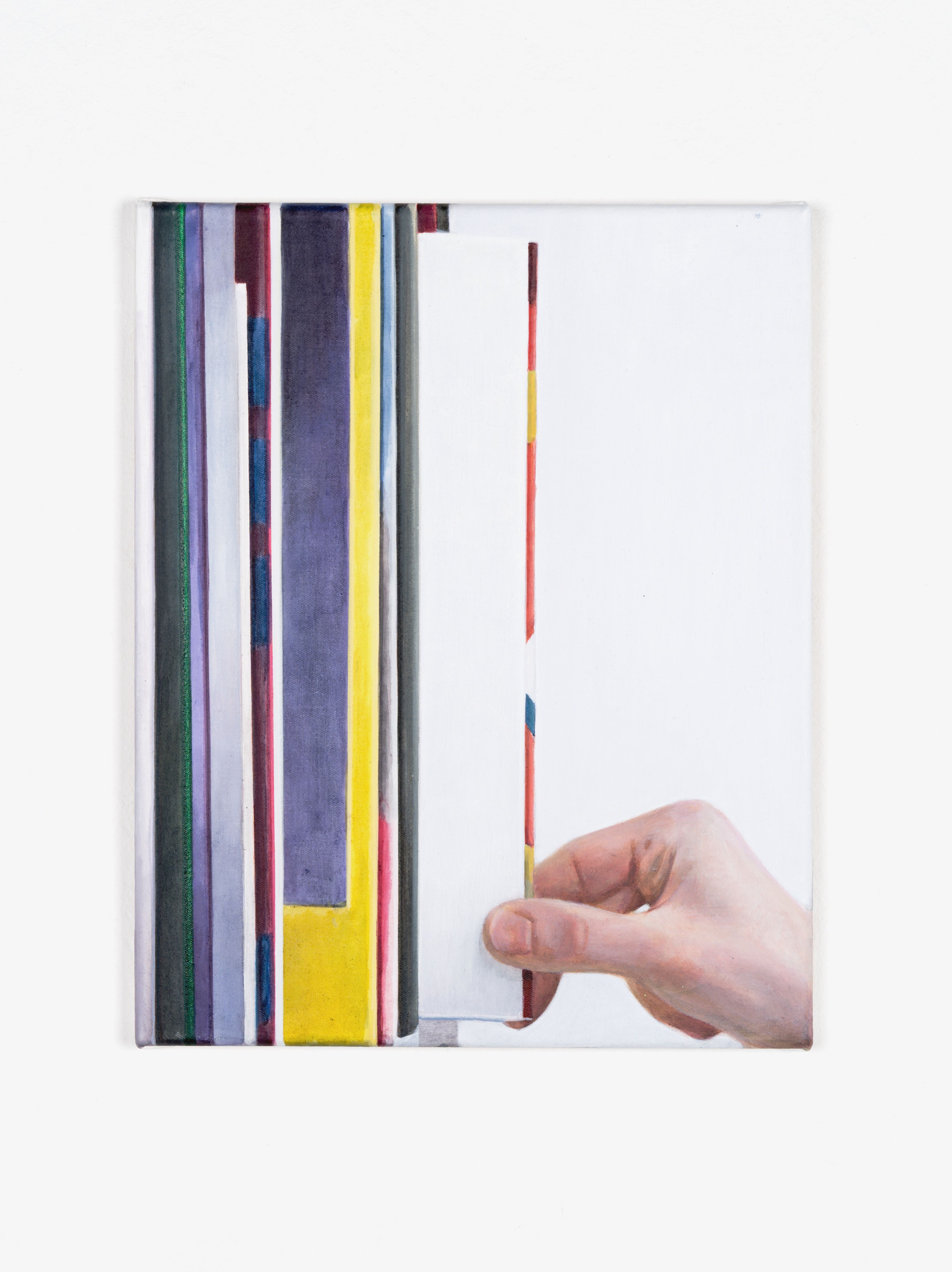

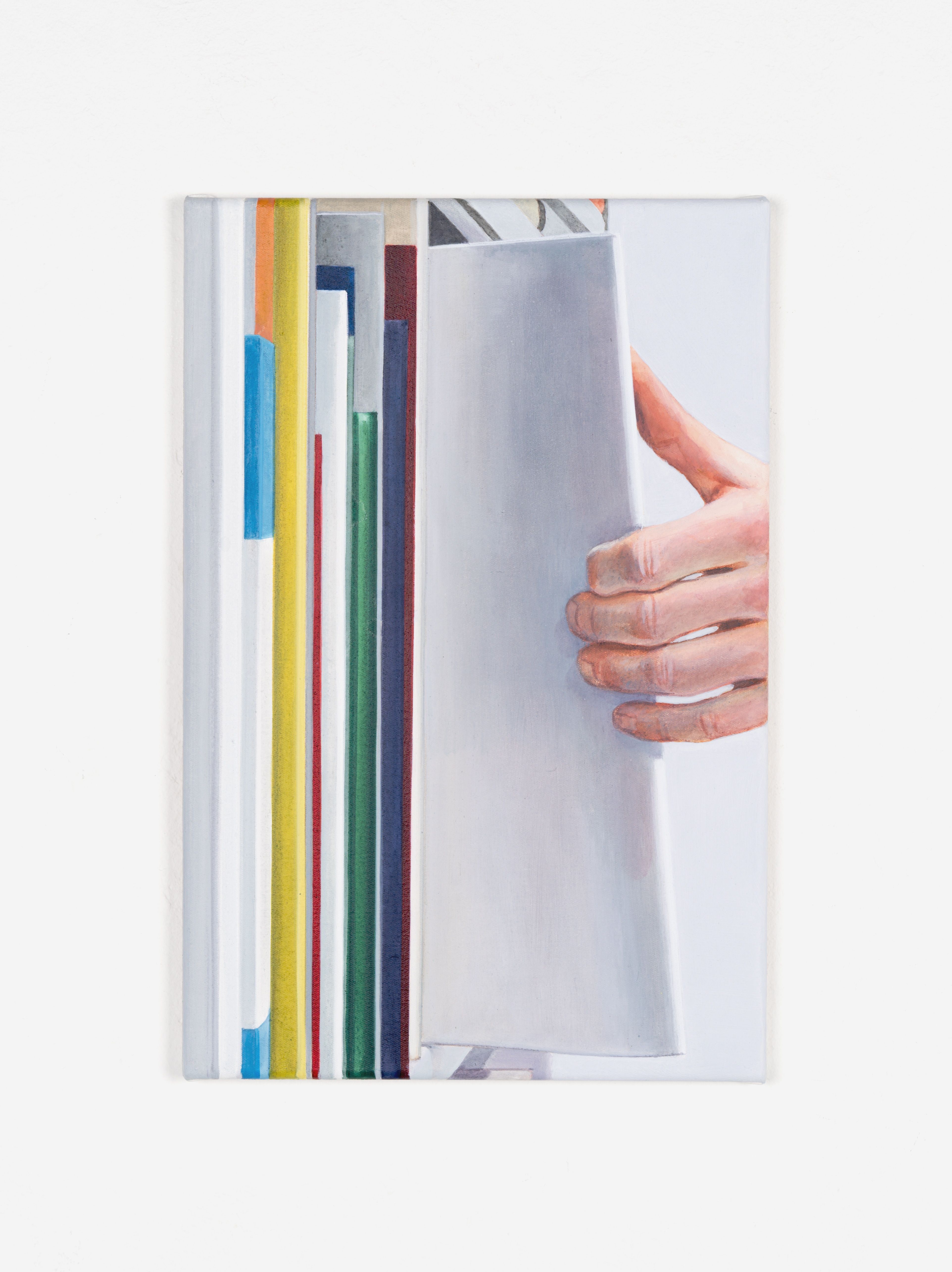

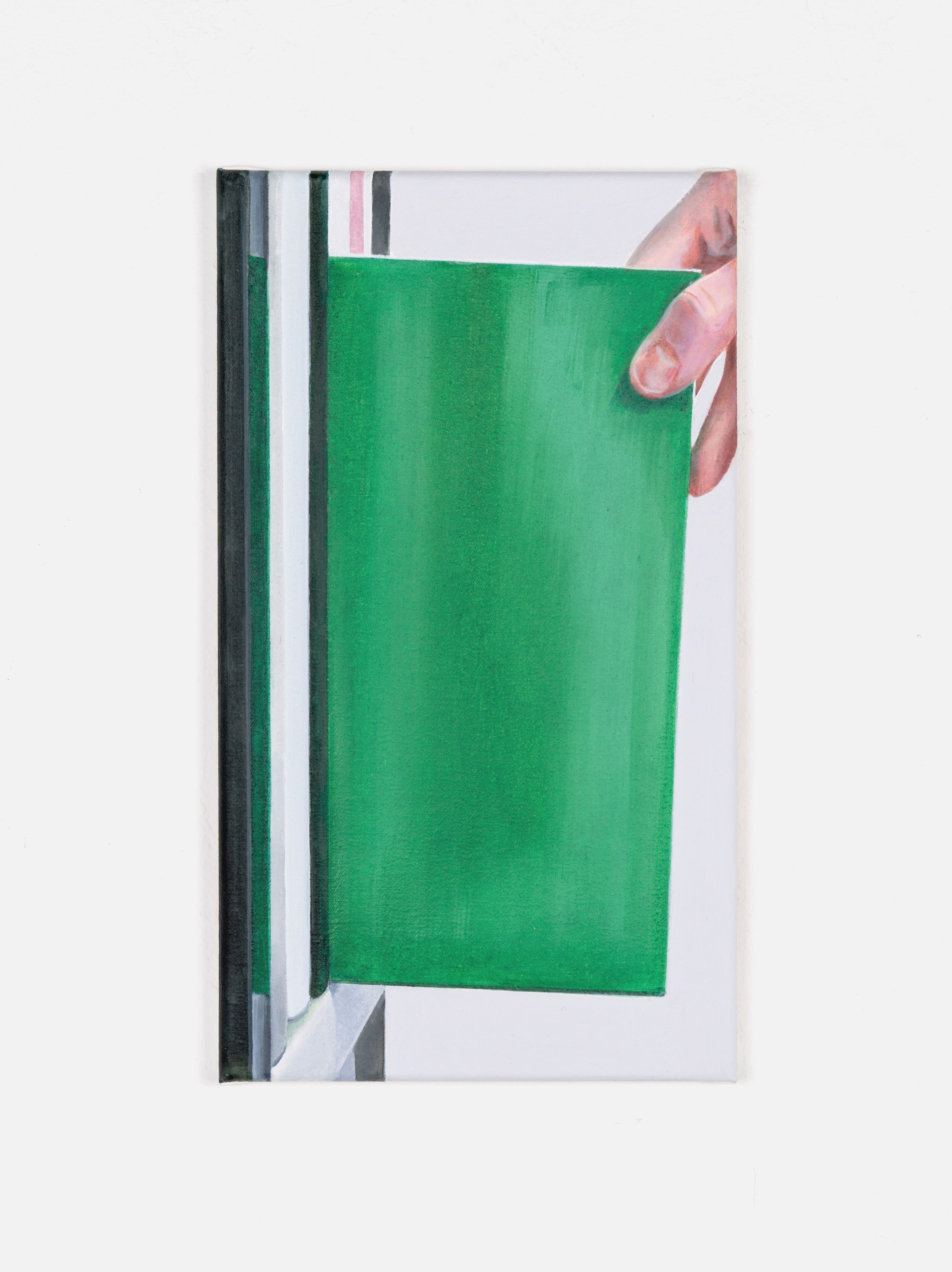

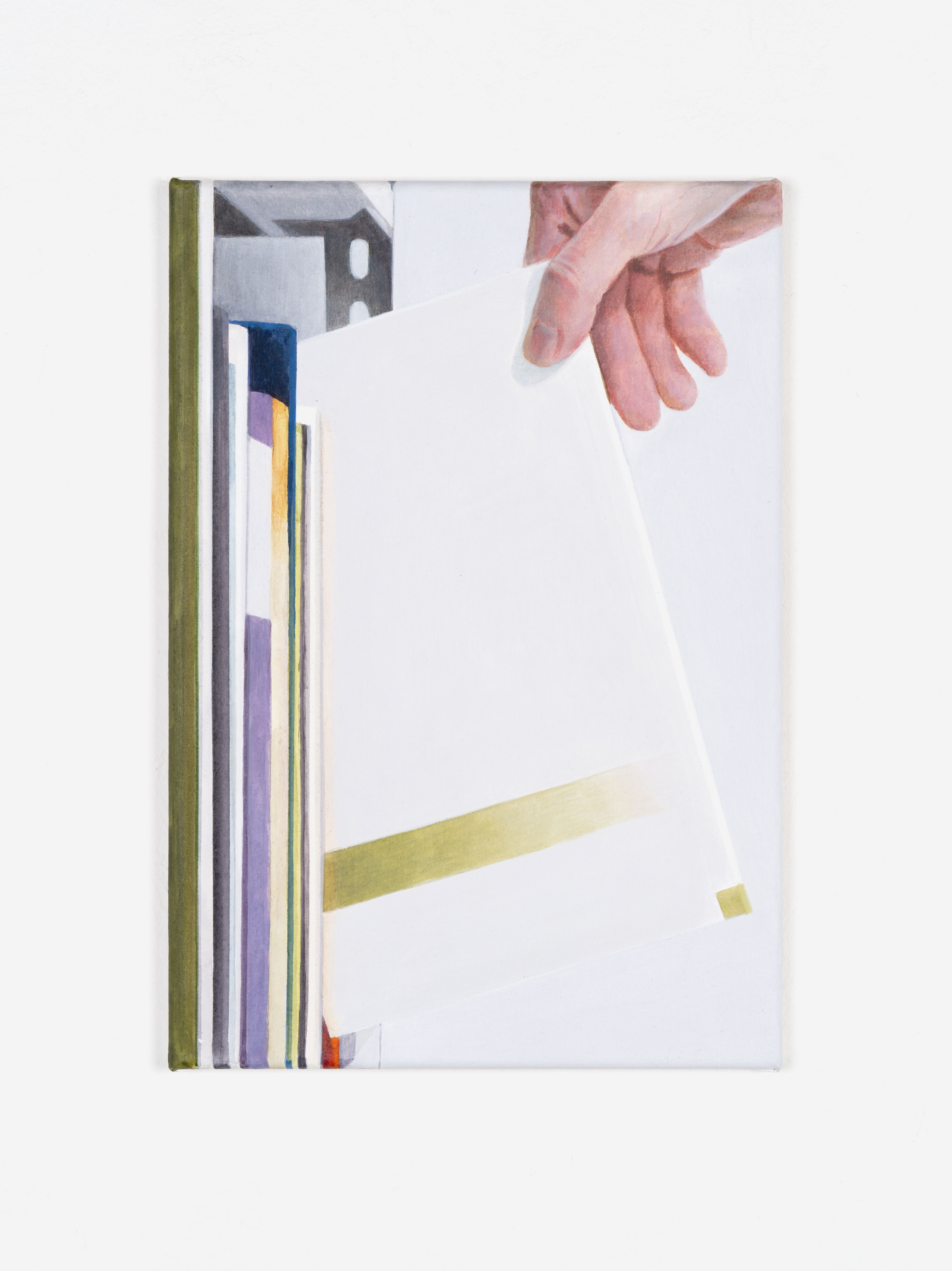

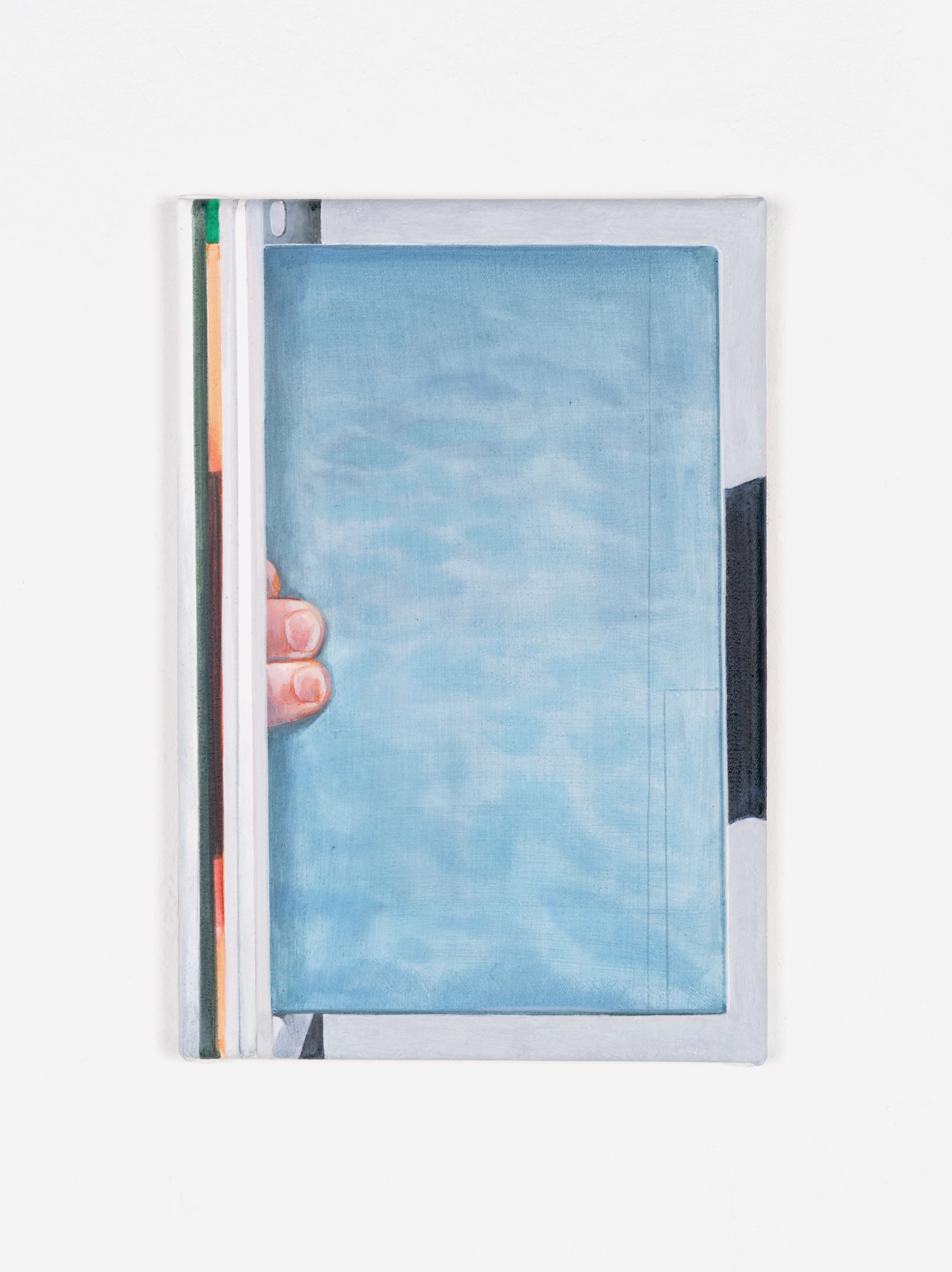

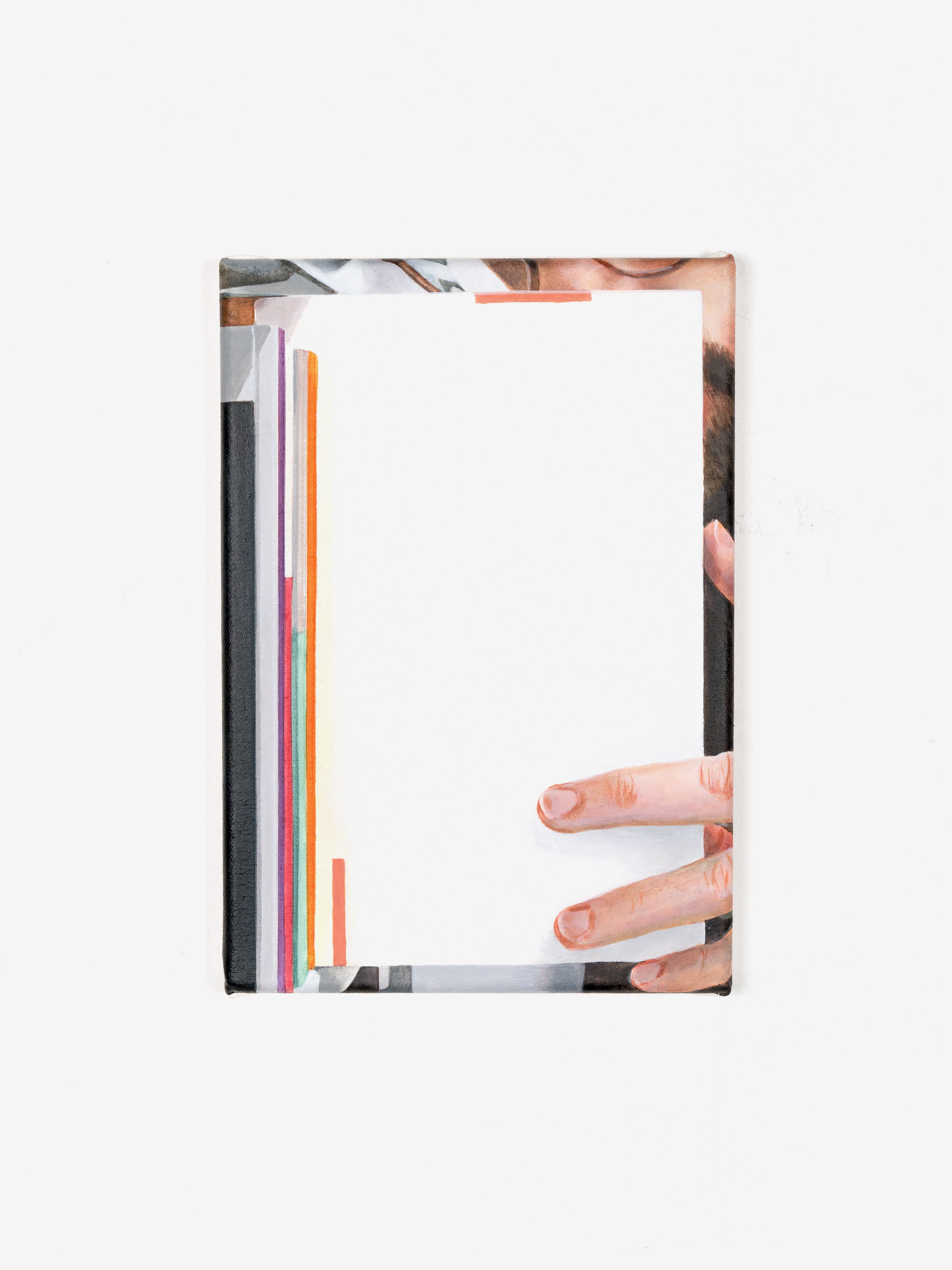

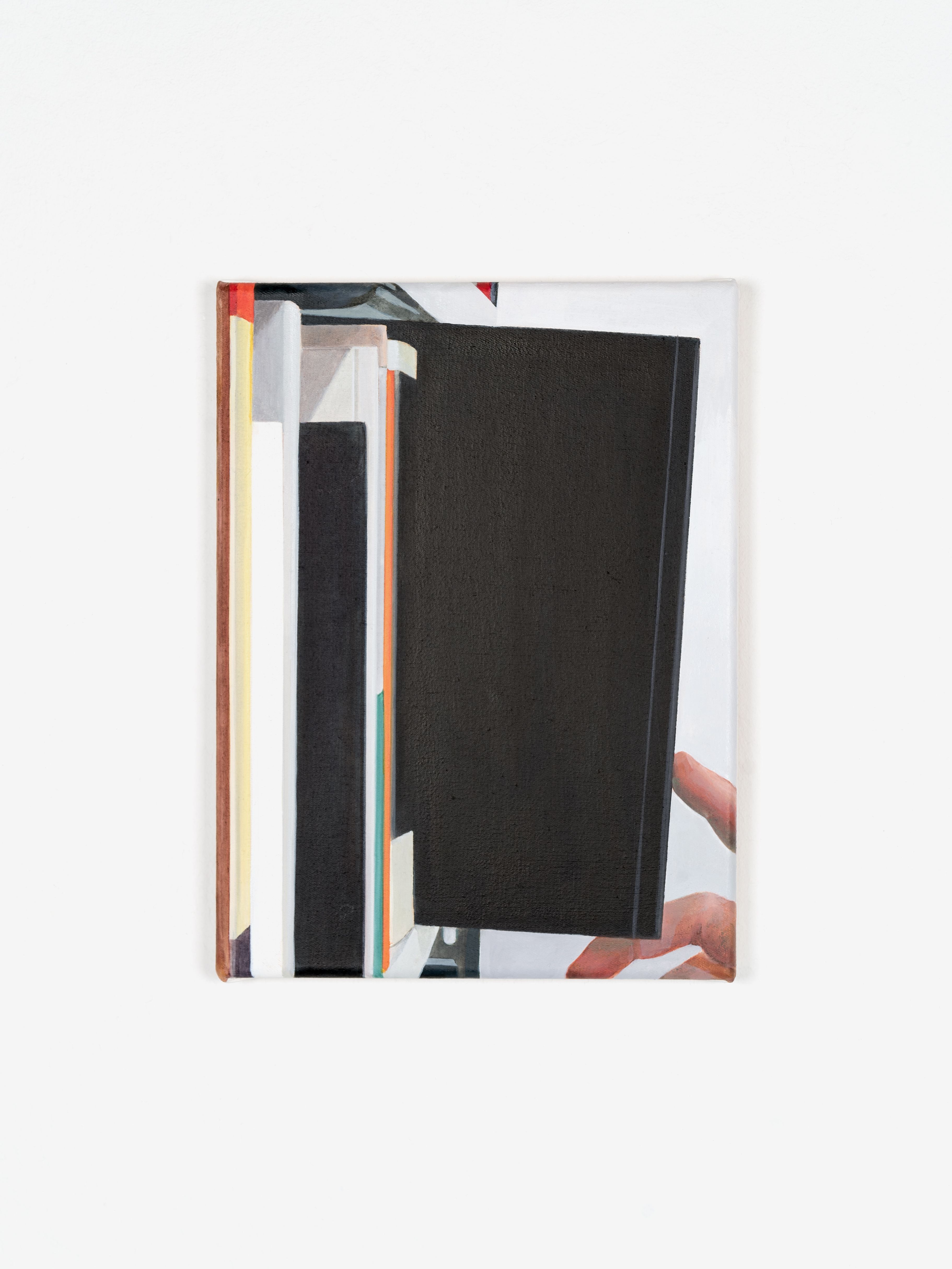

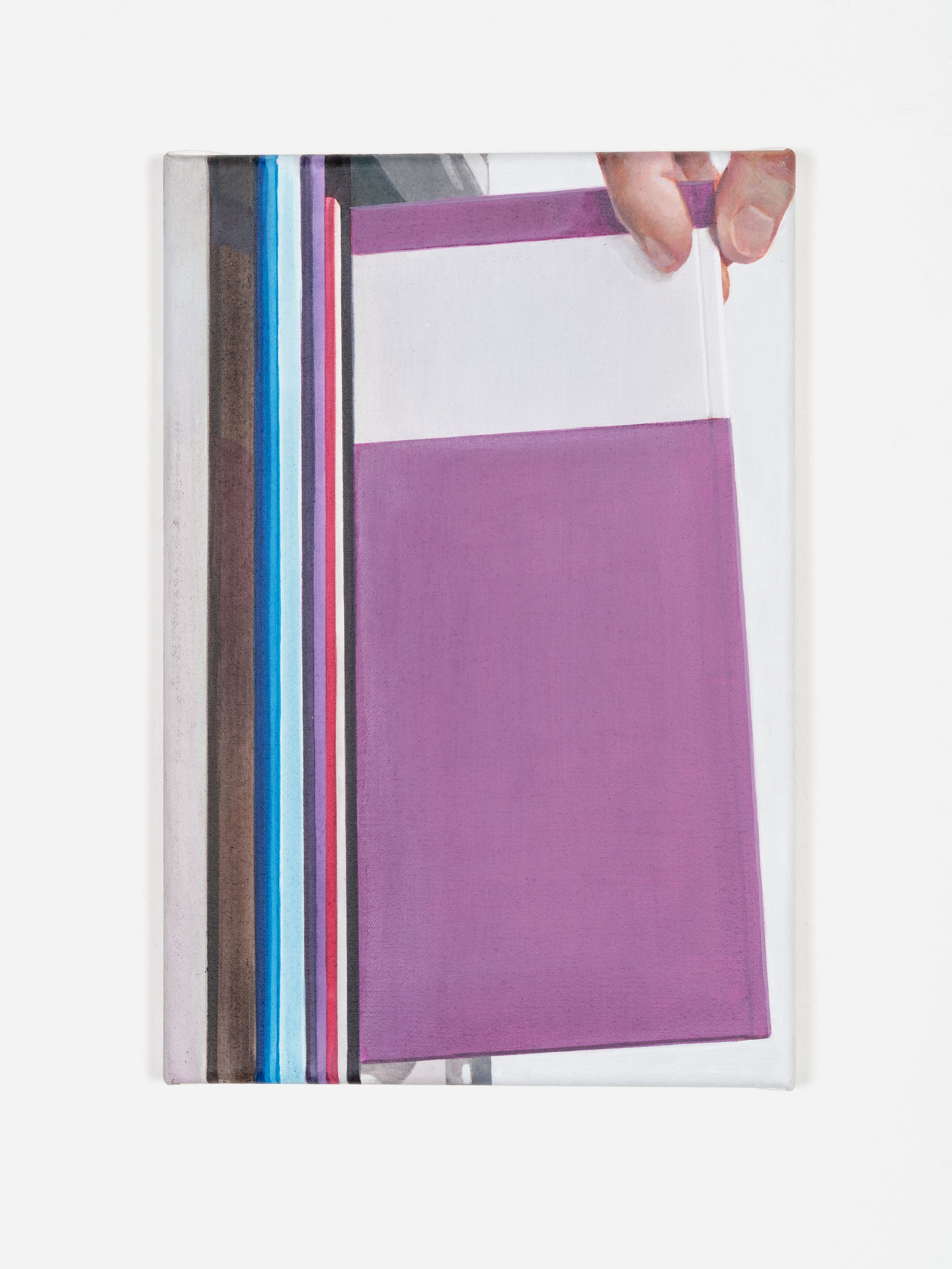

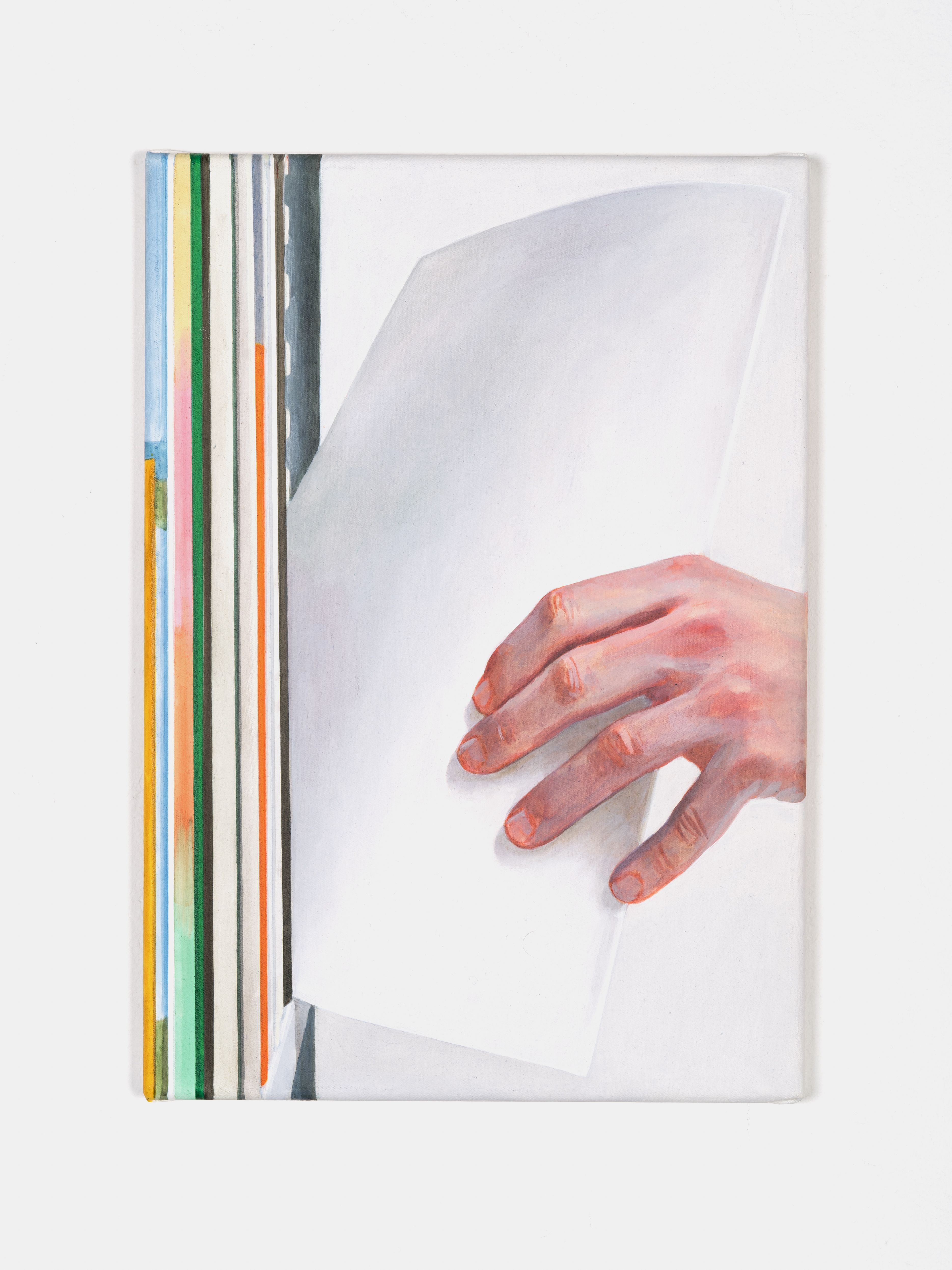

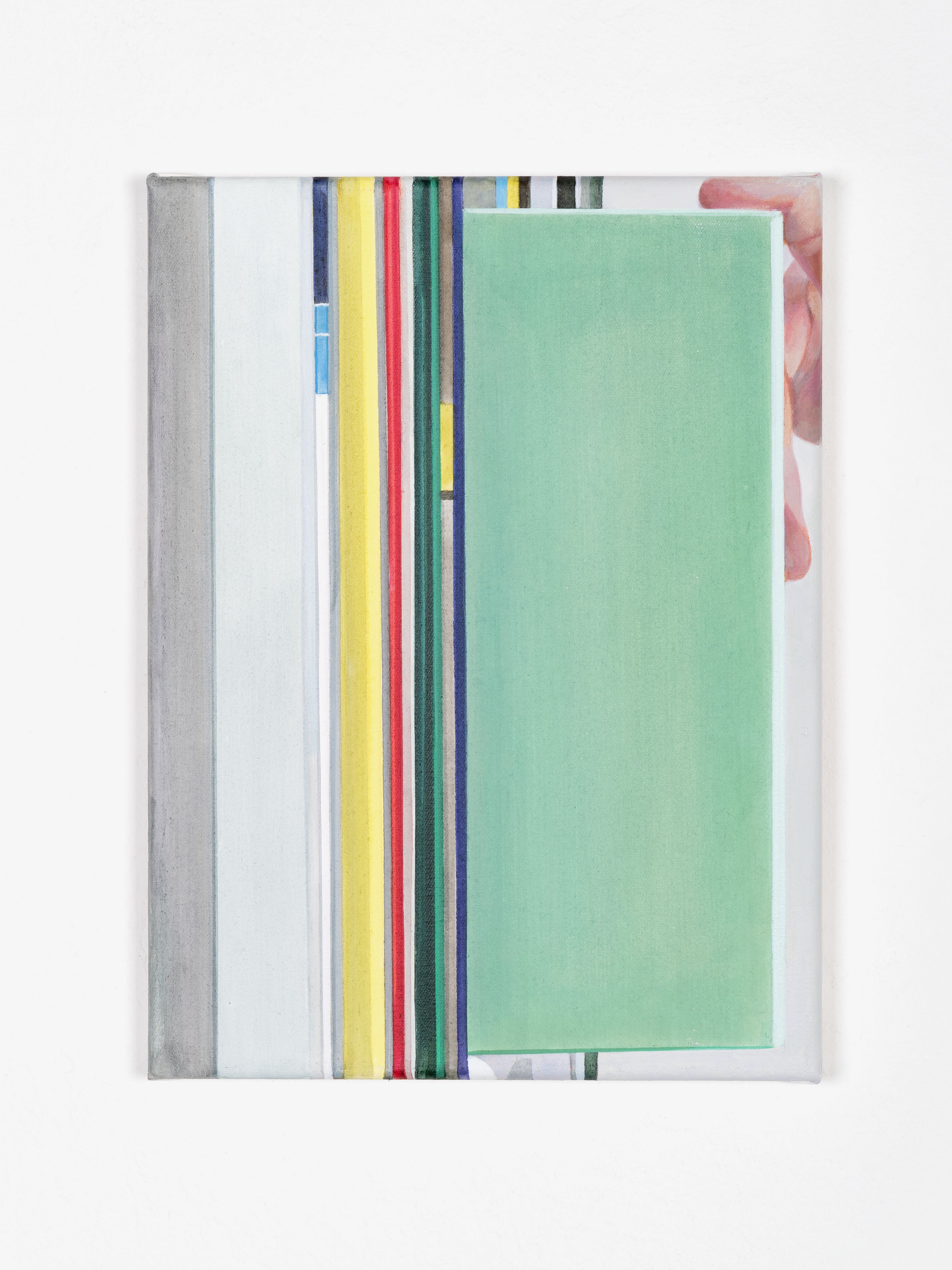

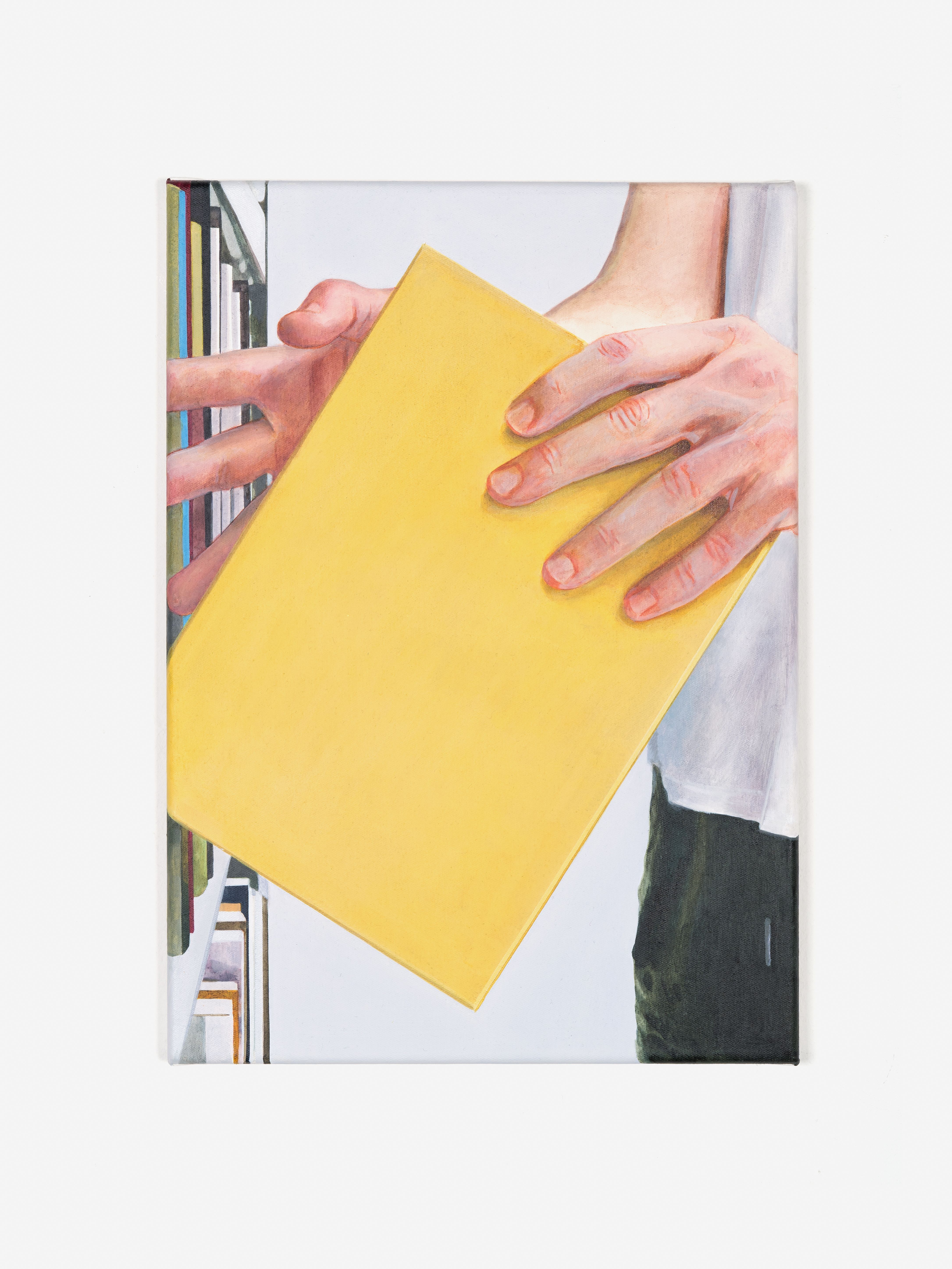

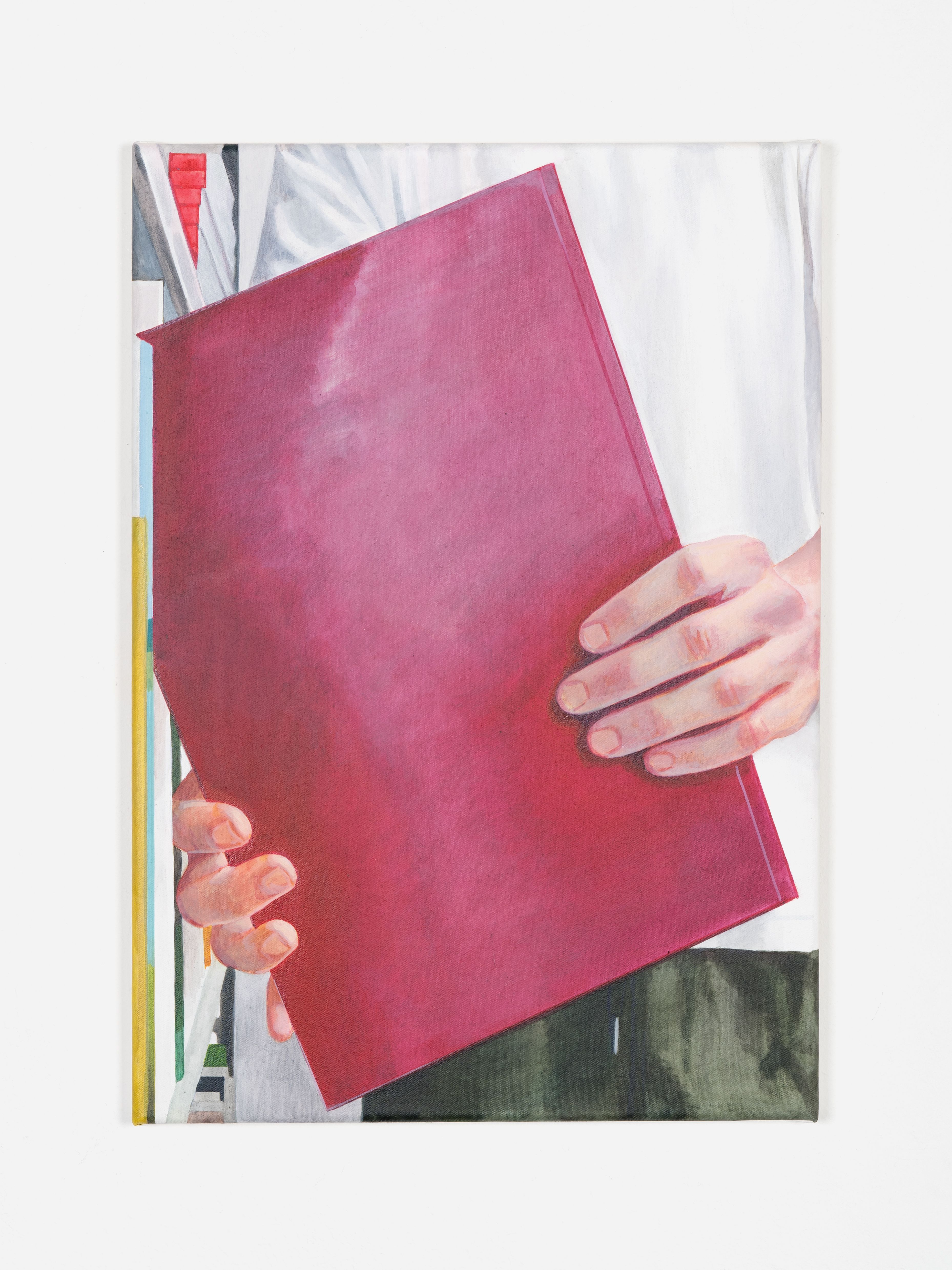

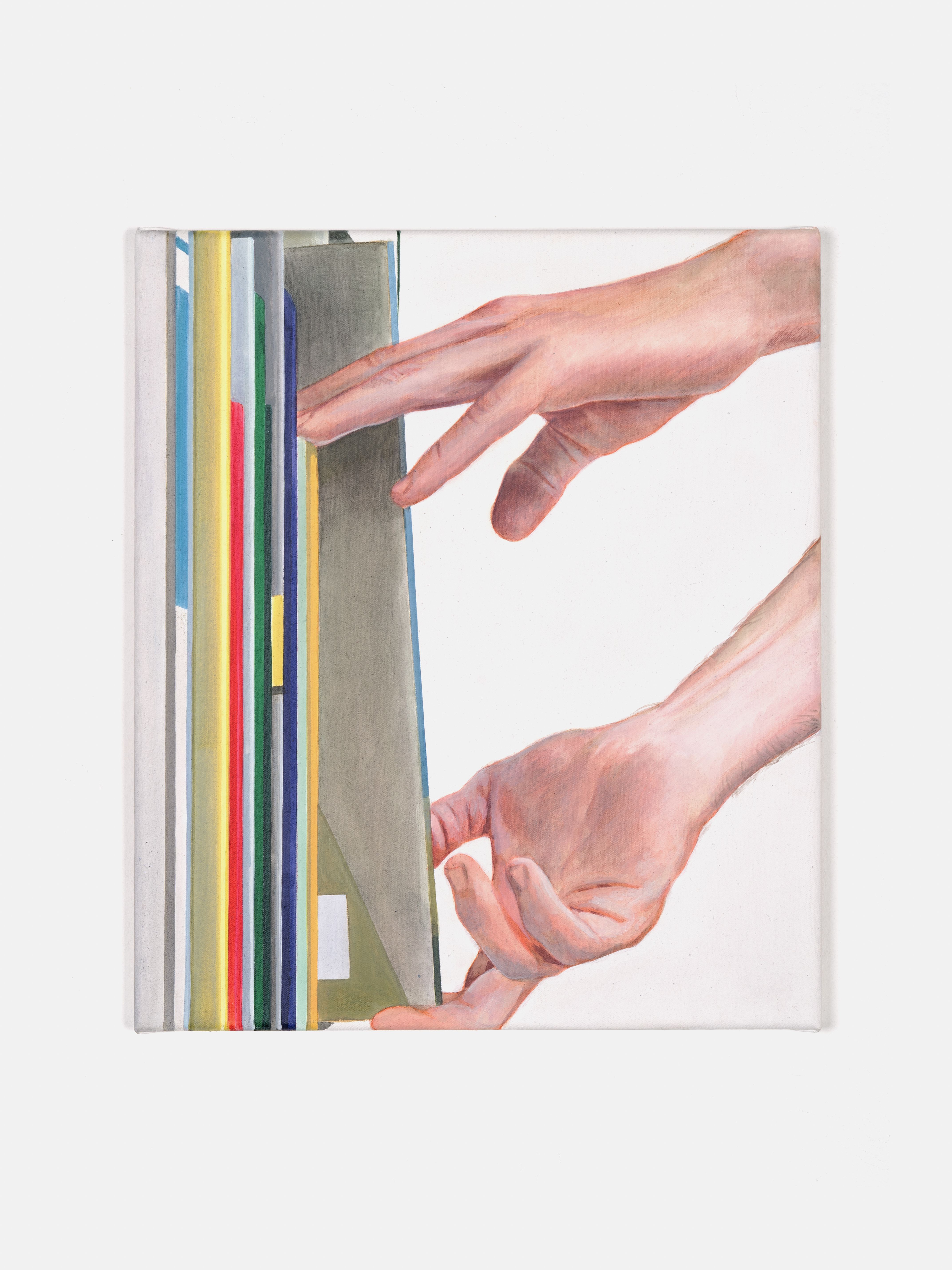

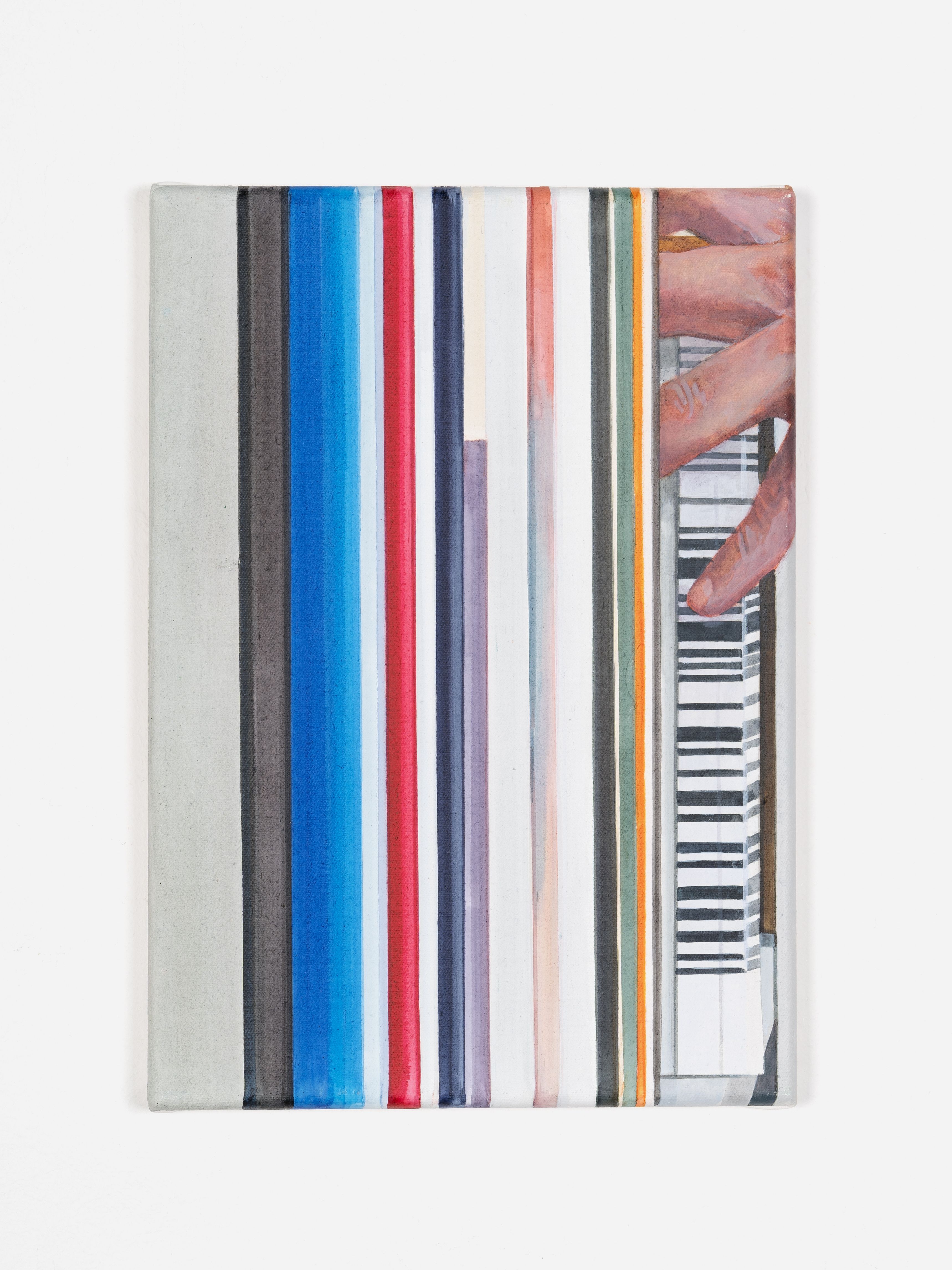

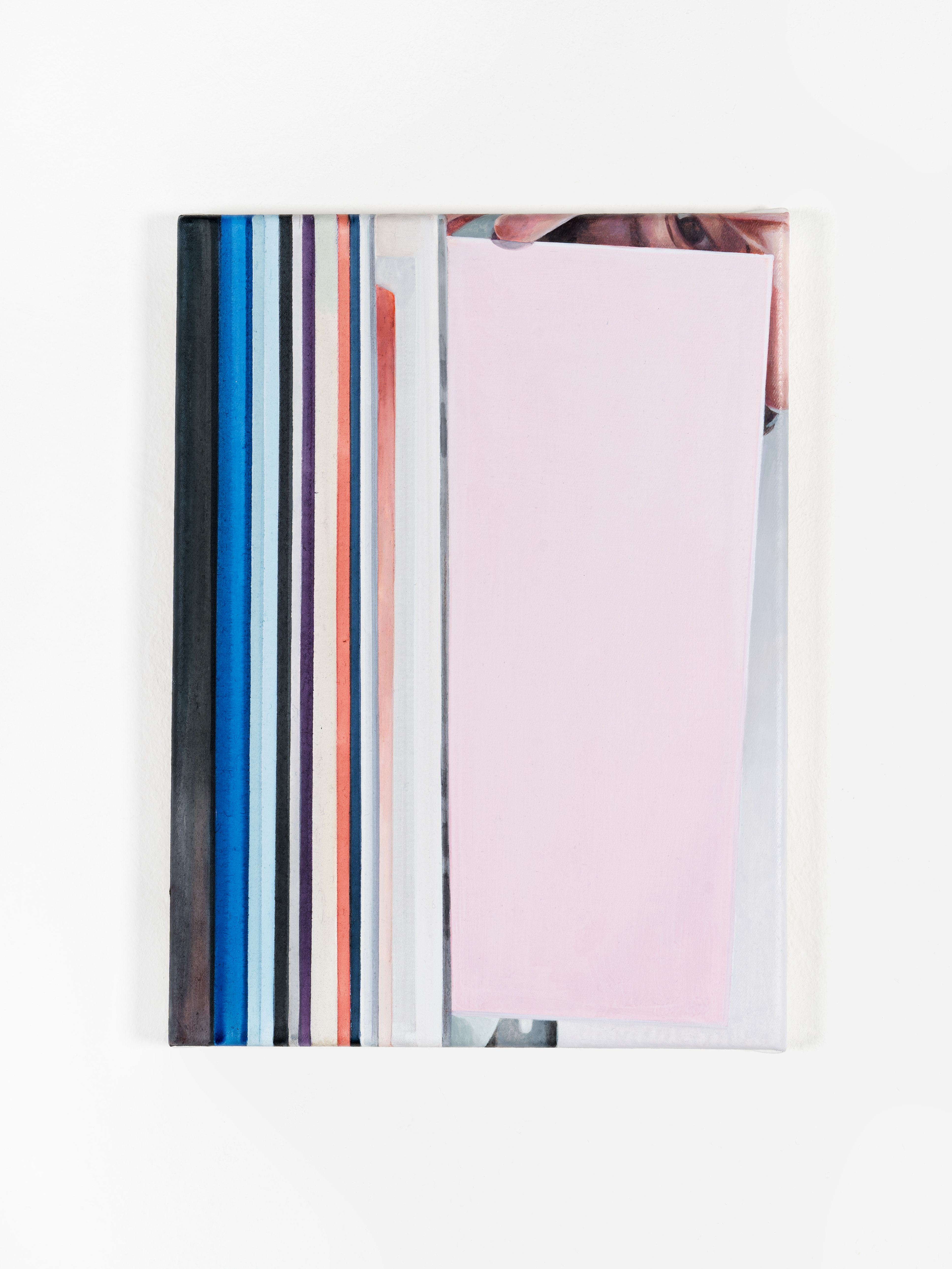

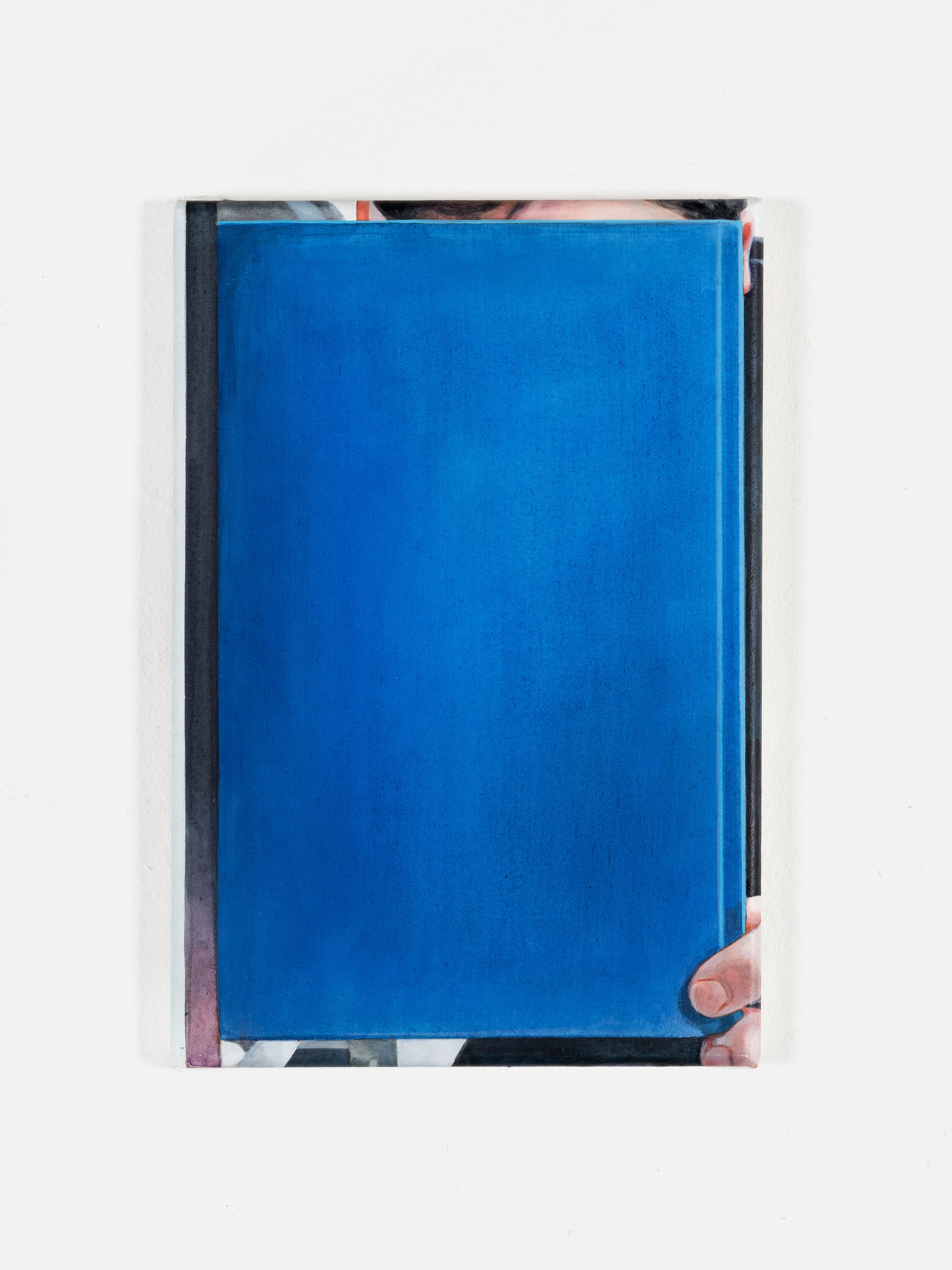

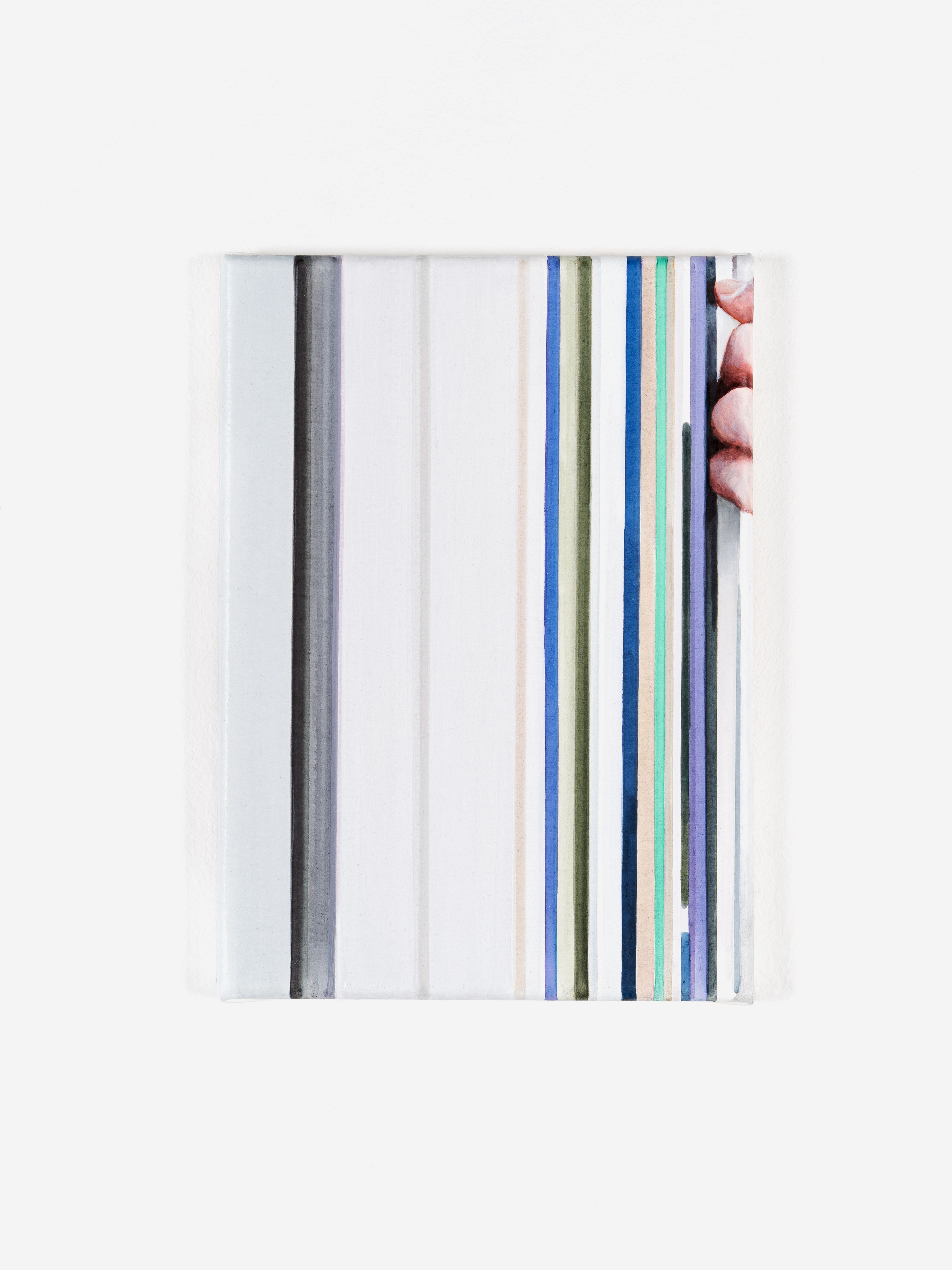

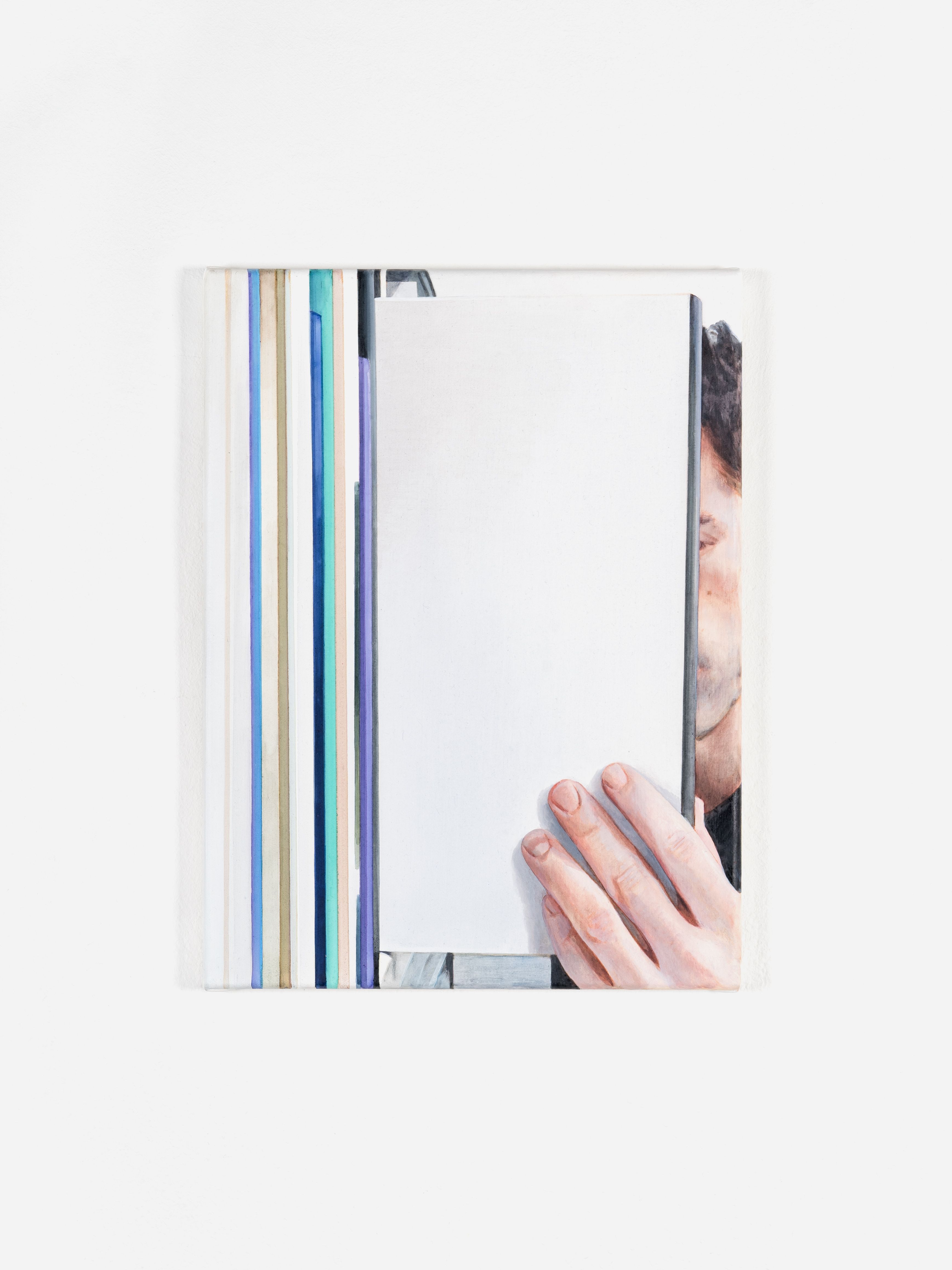

A—Z

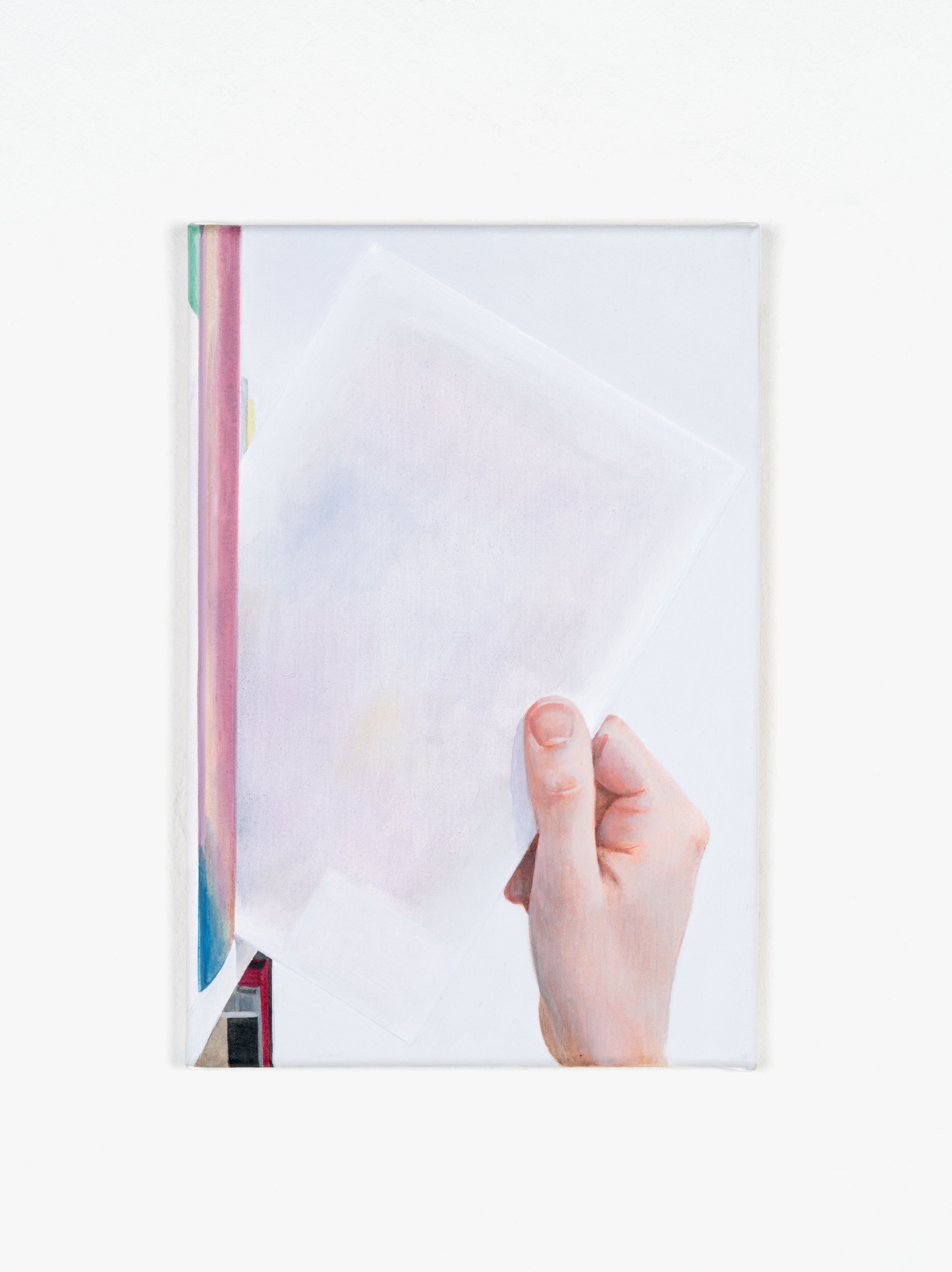

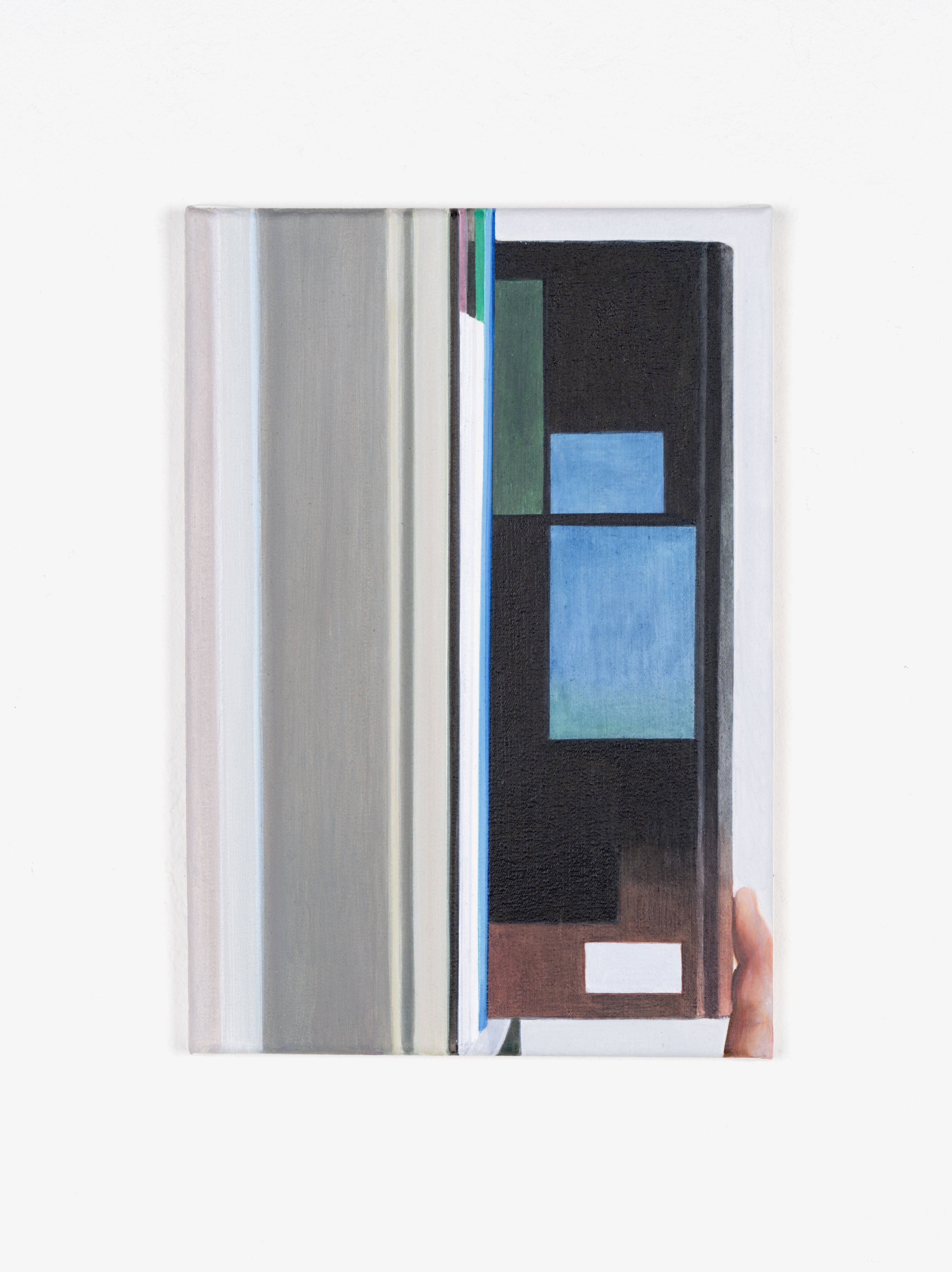

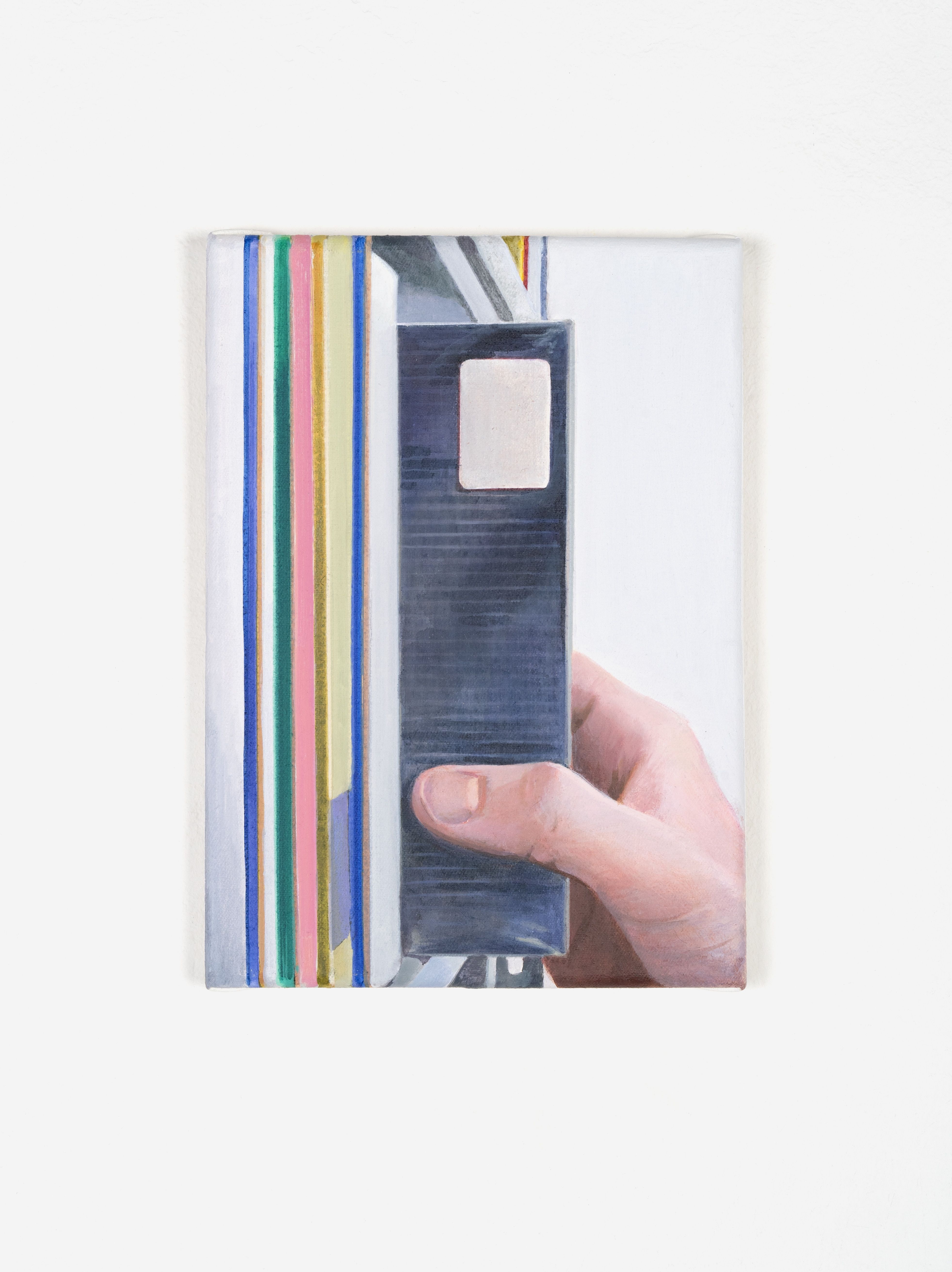

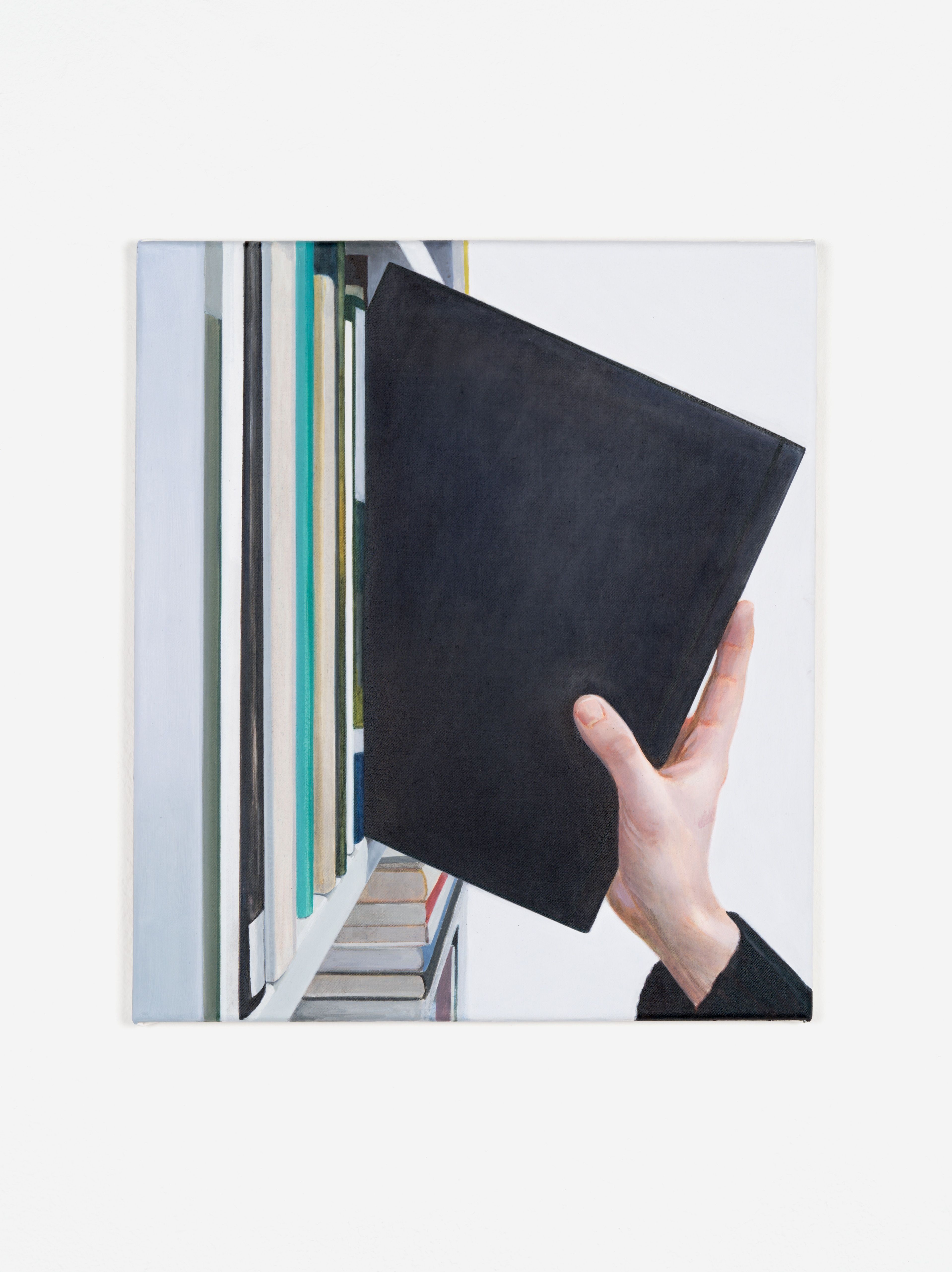

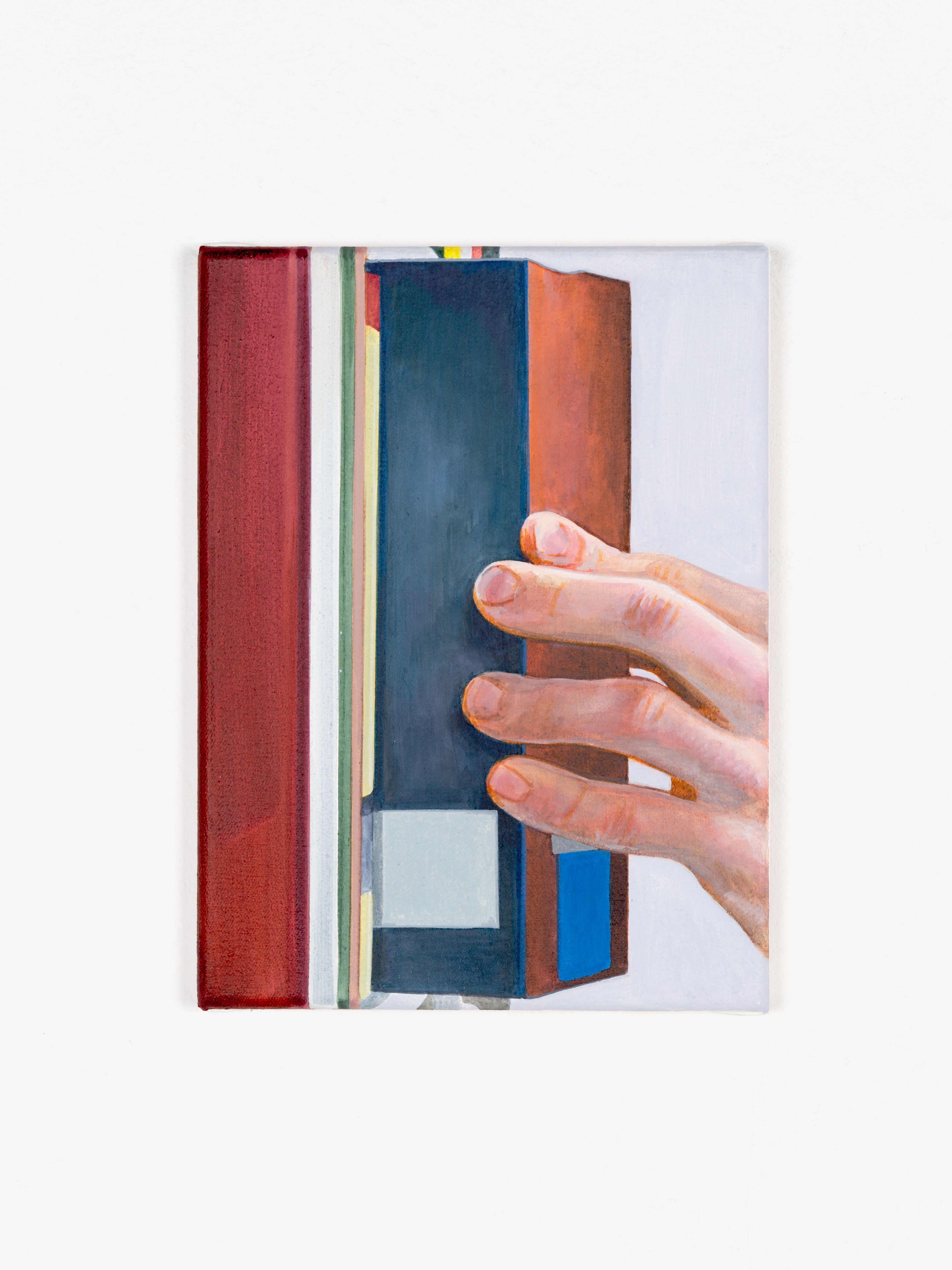

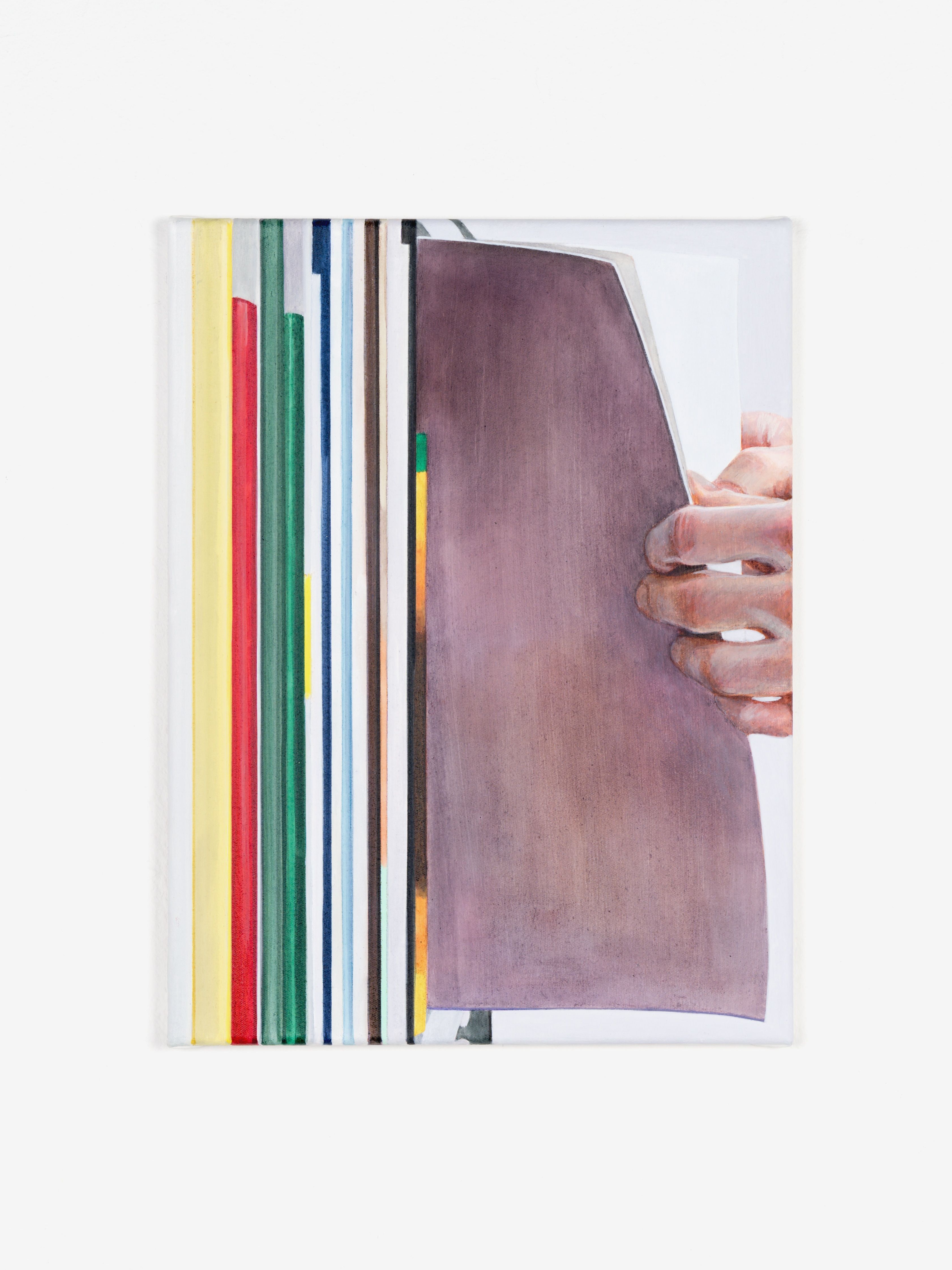

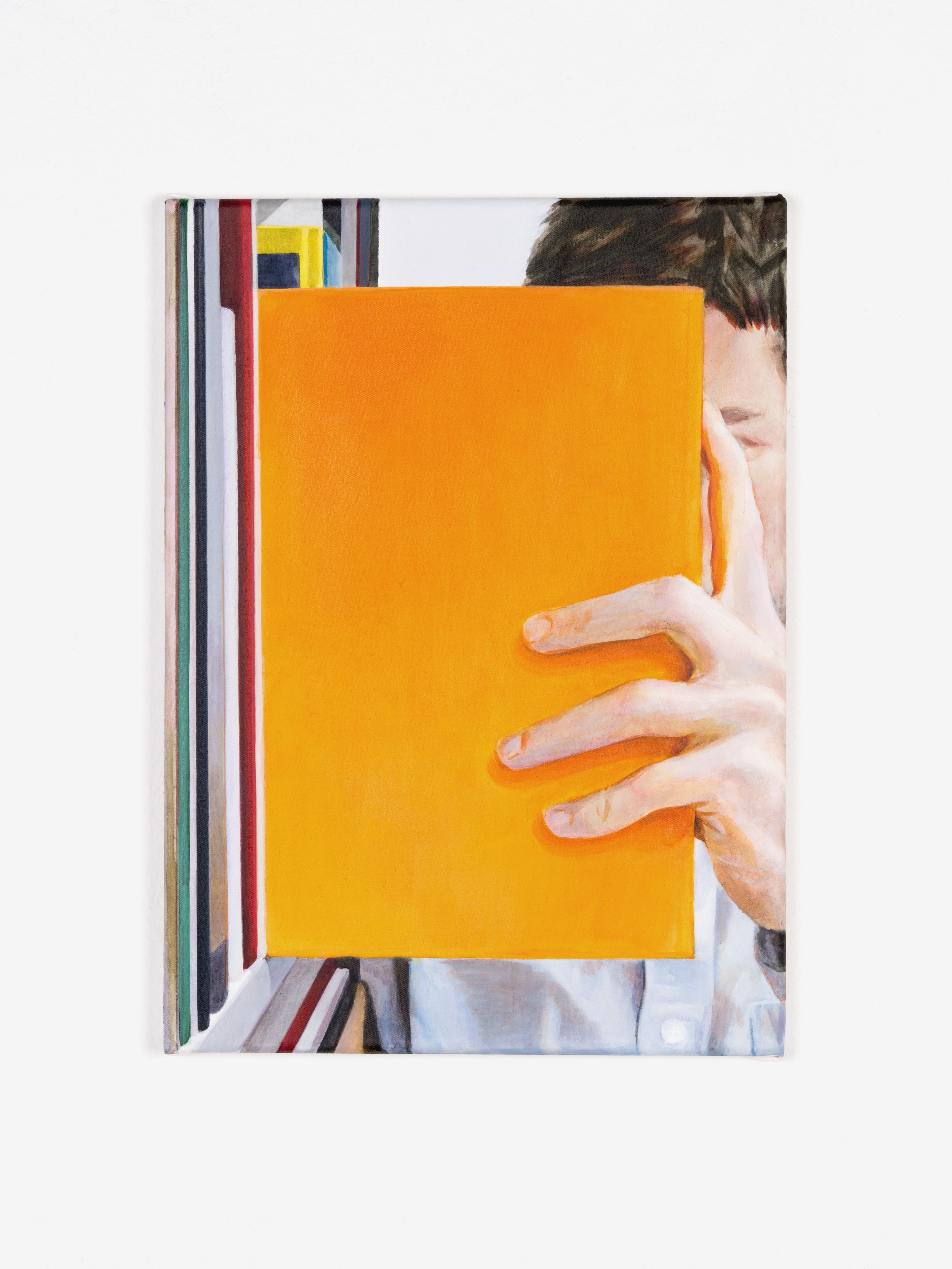

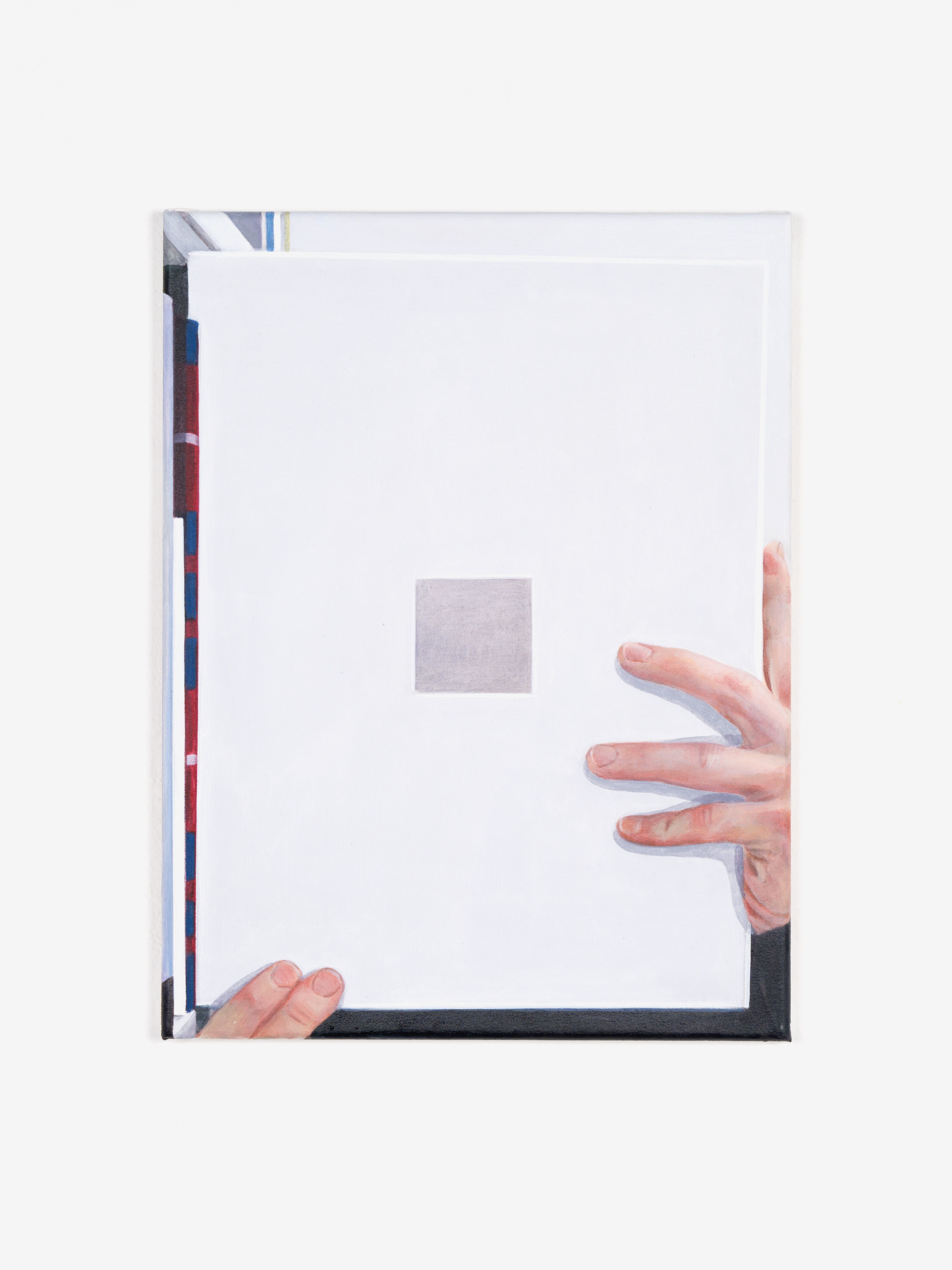

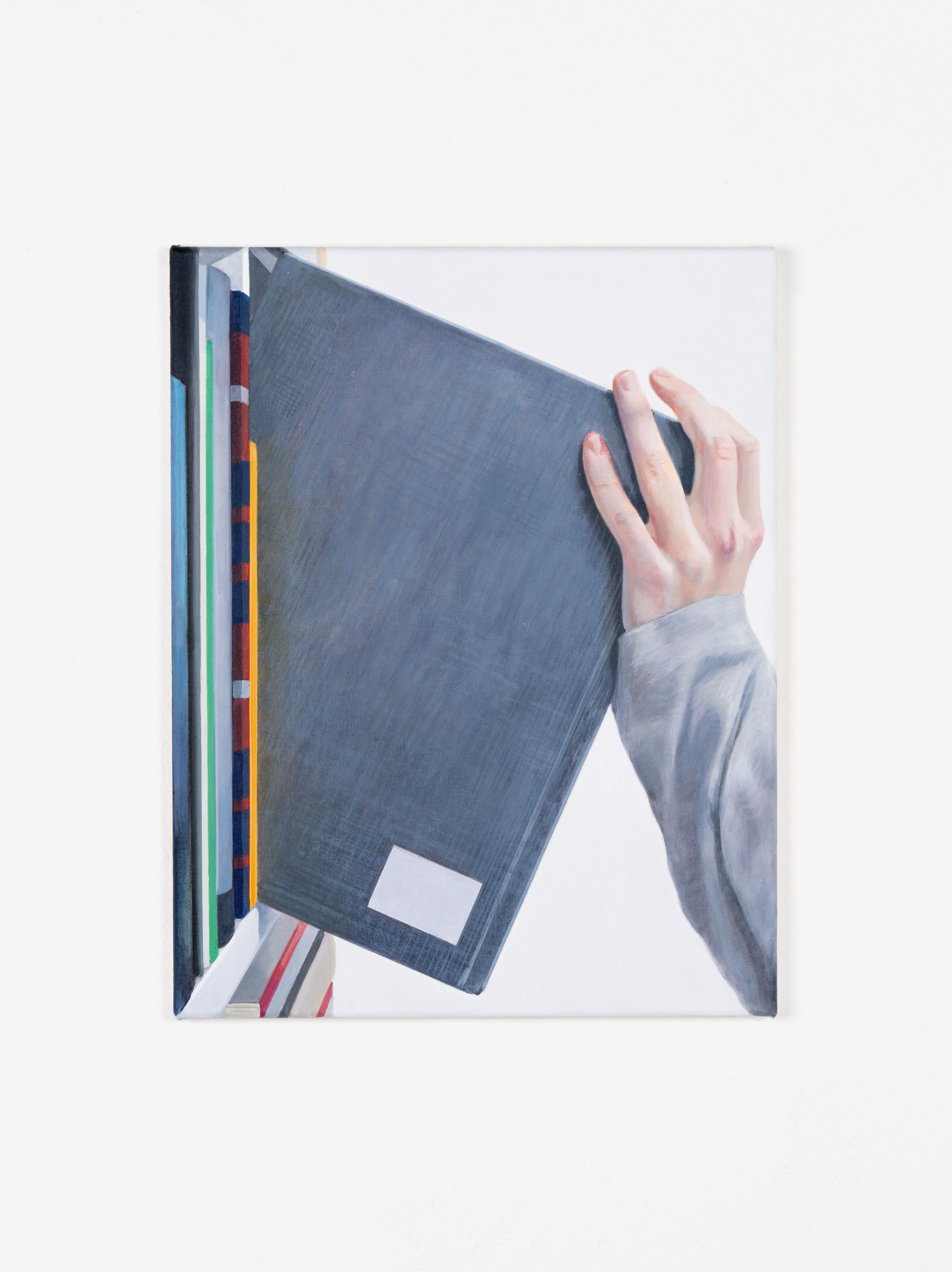

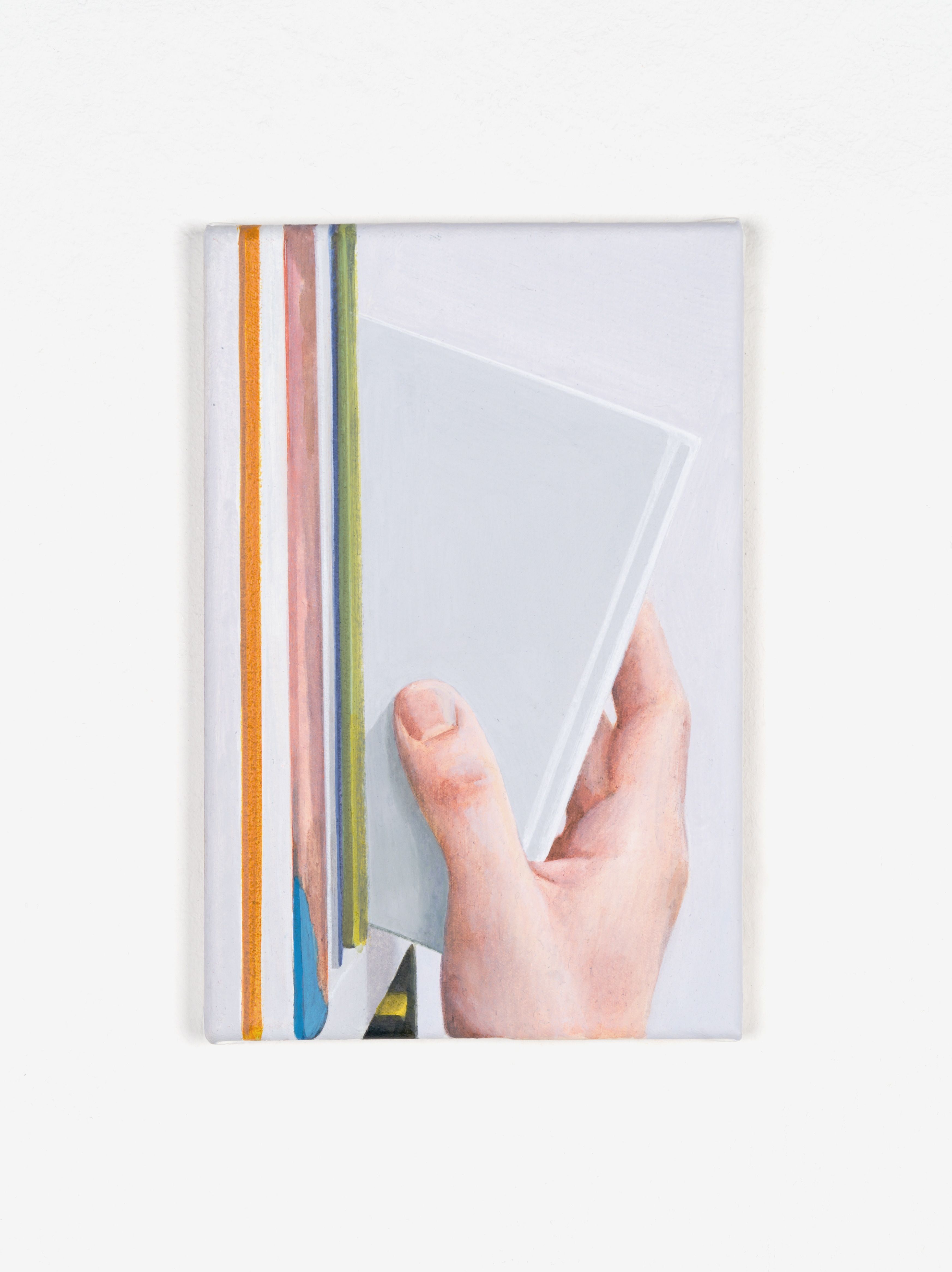

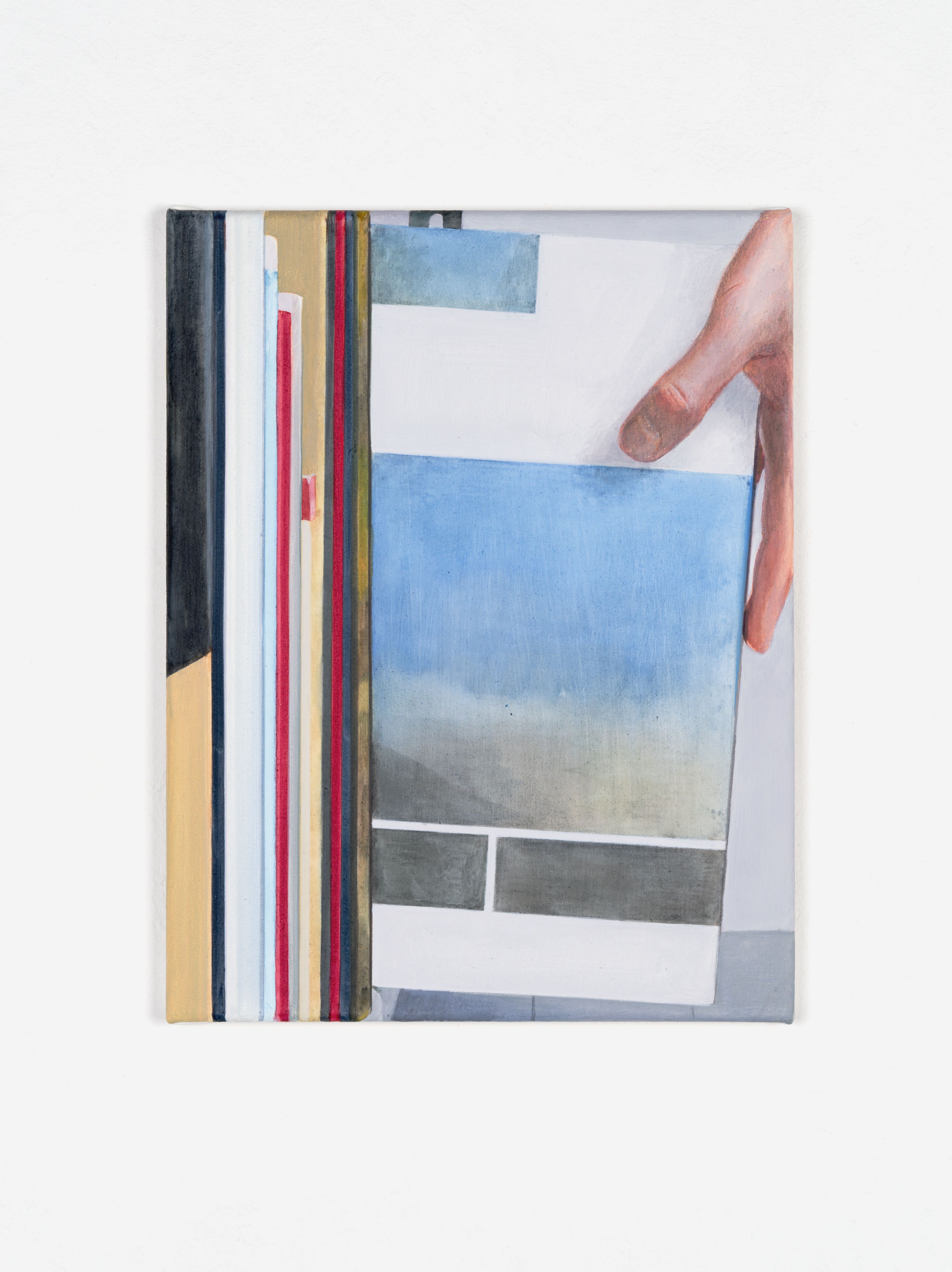

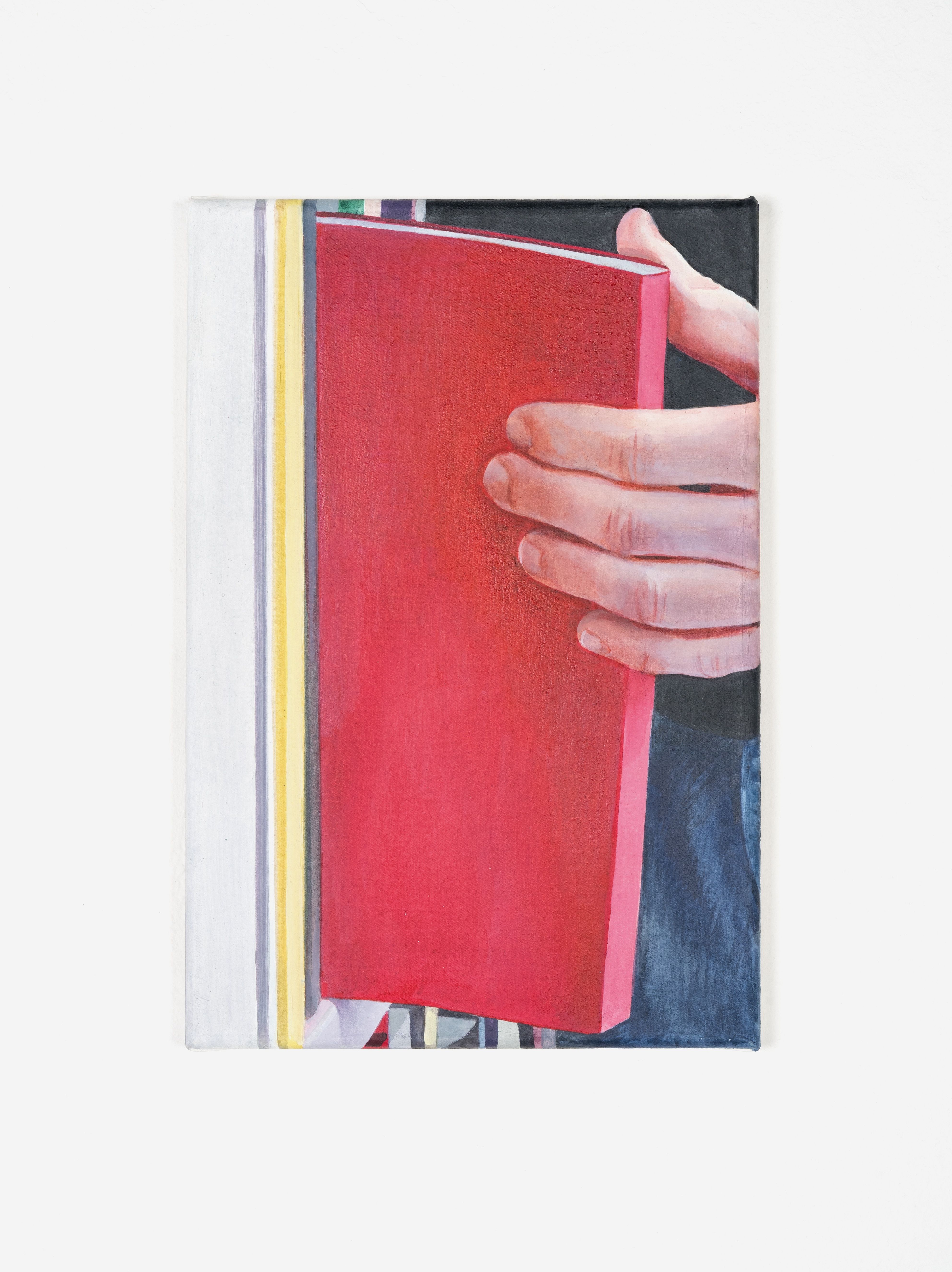

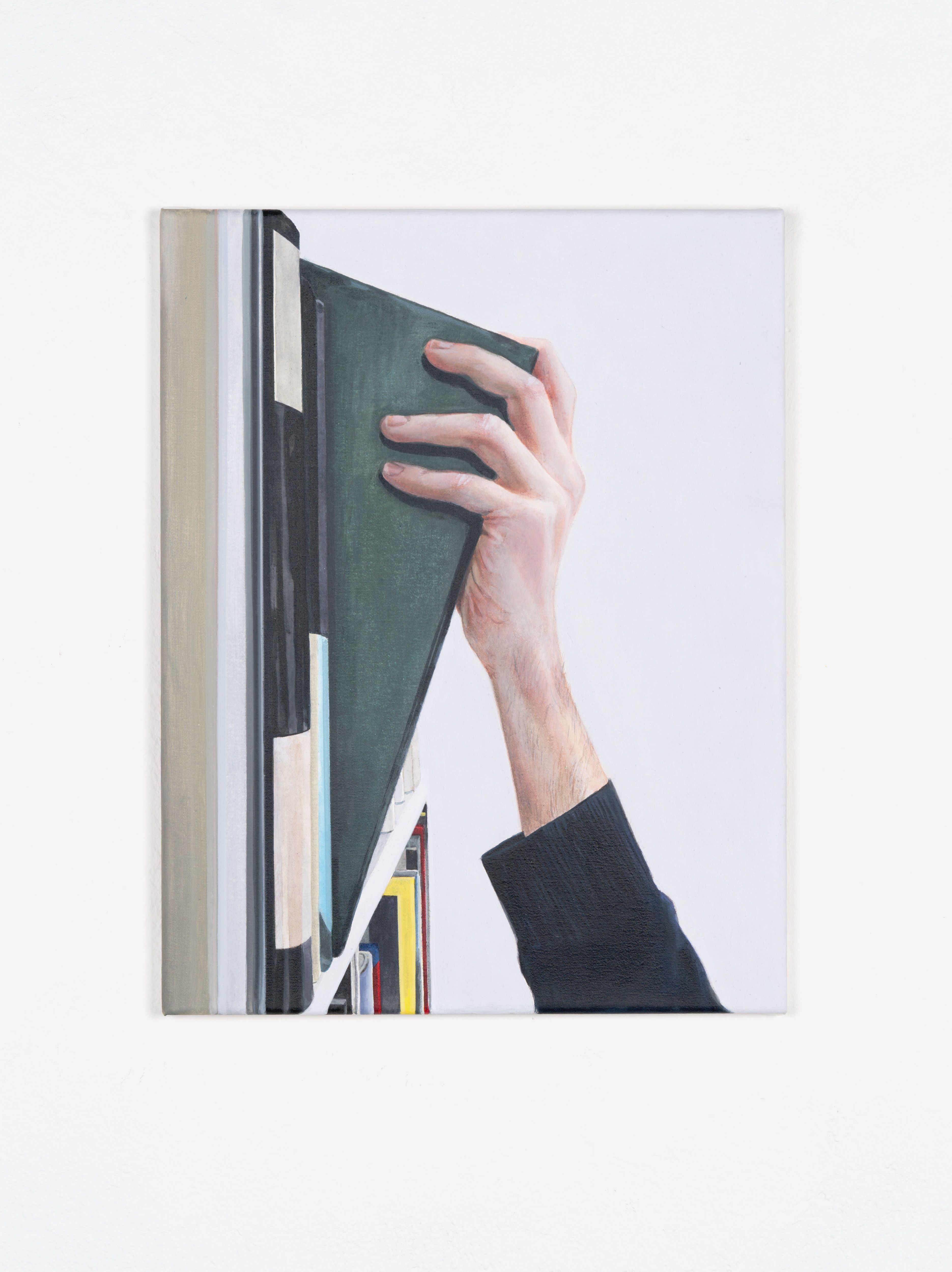

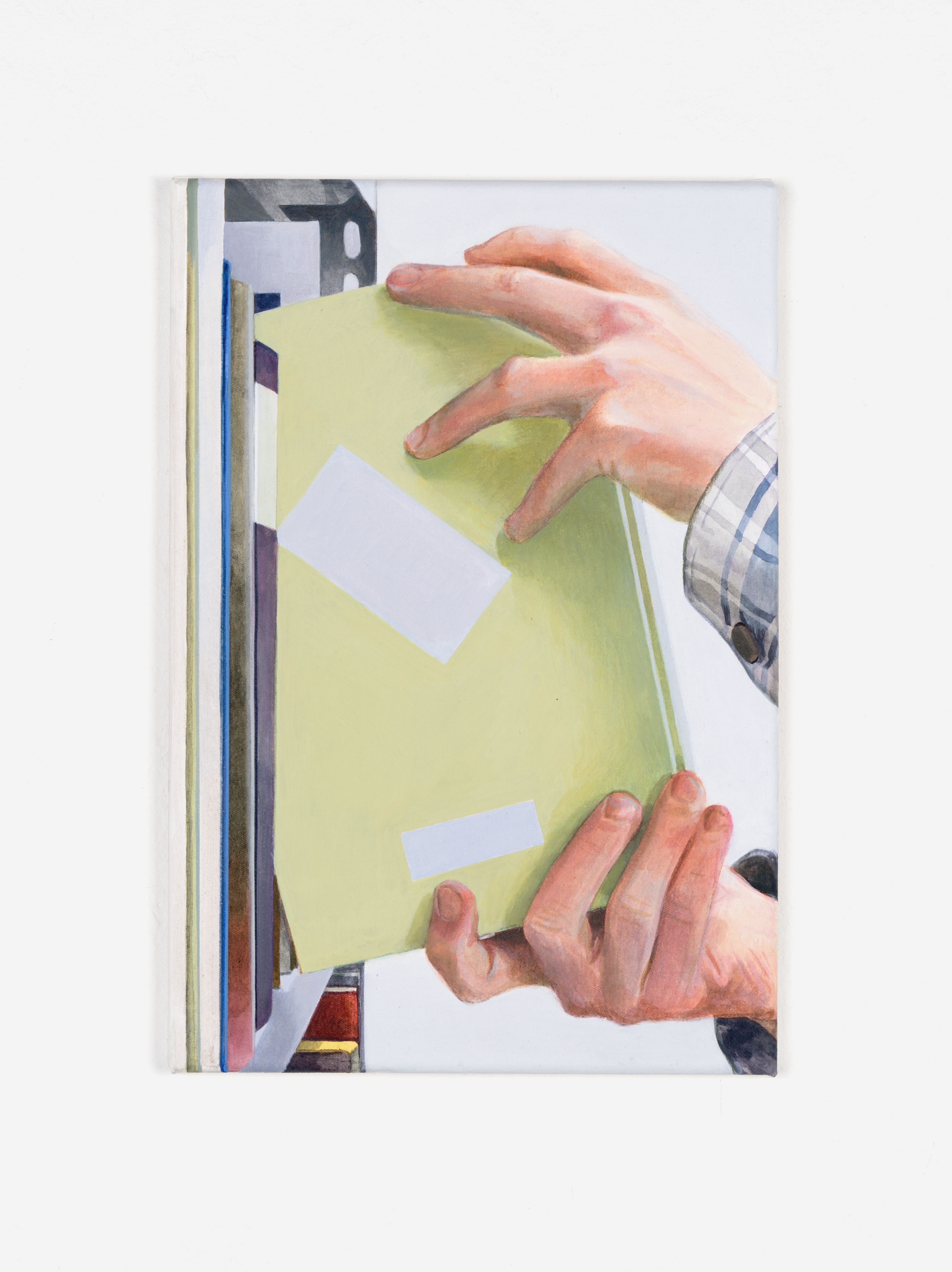

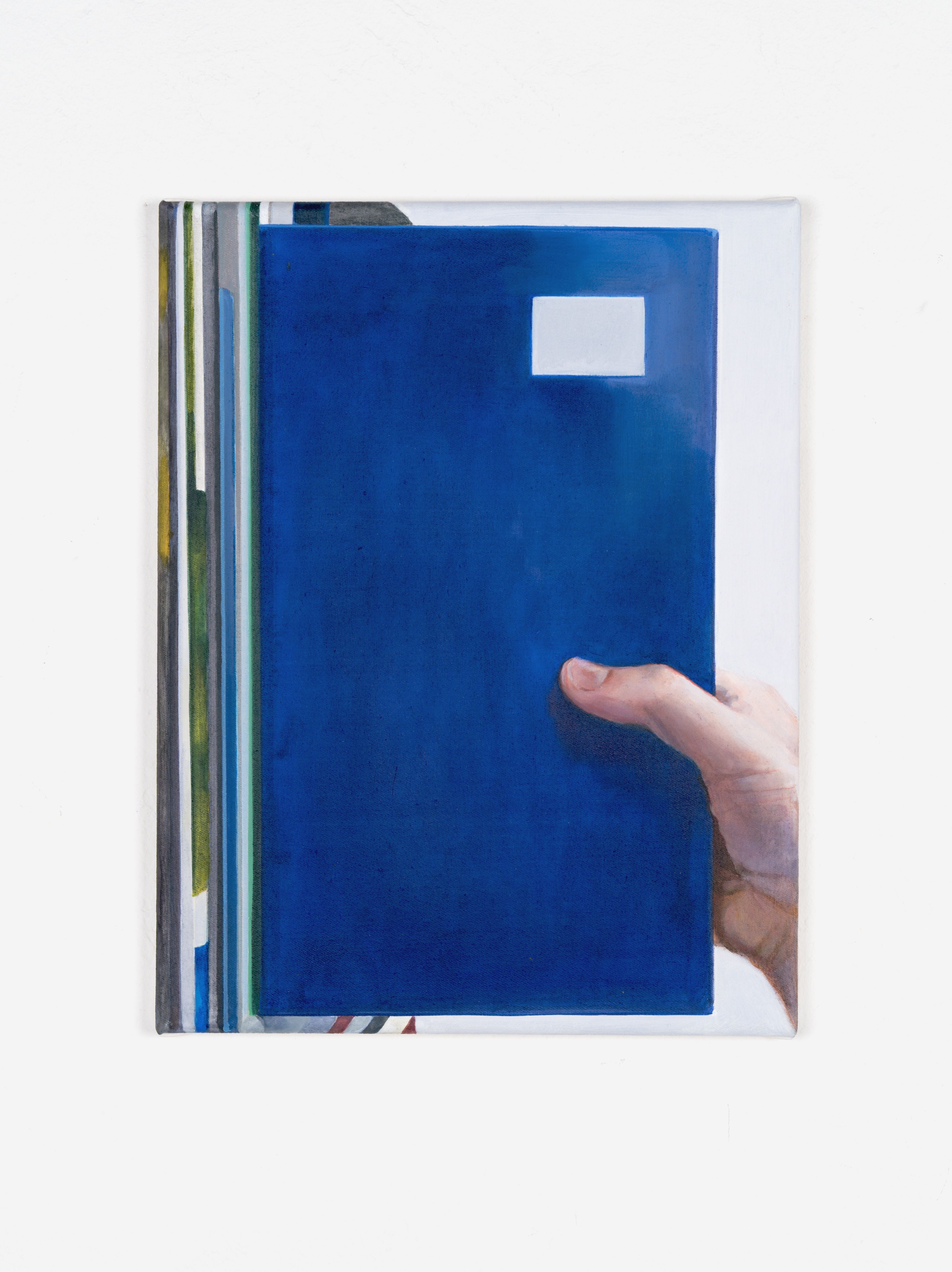

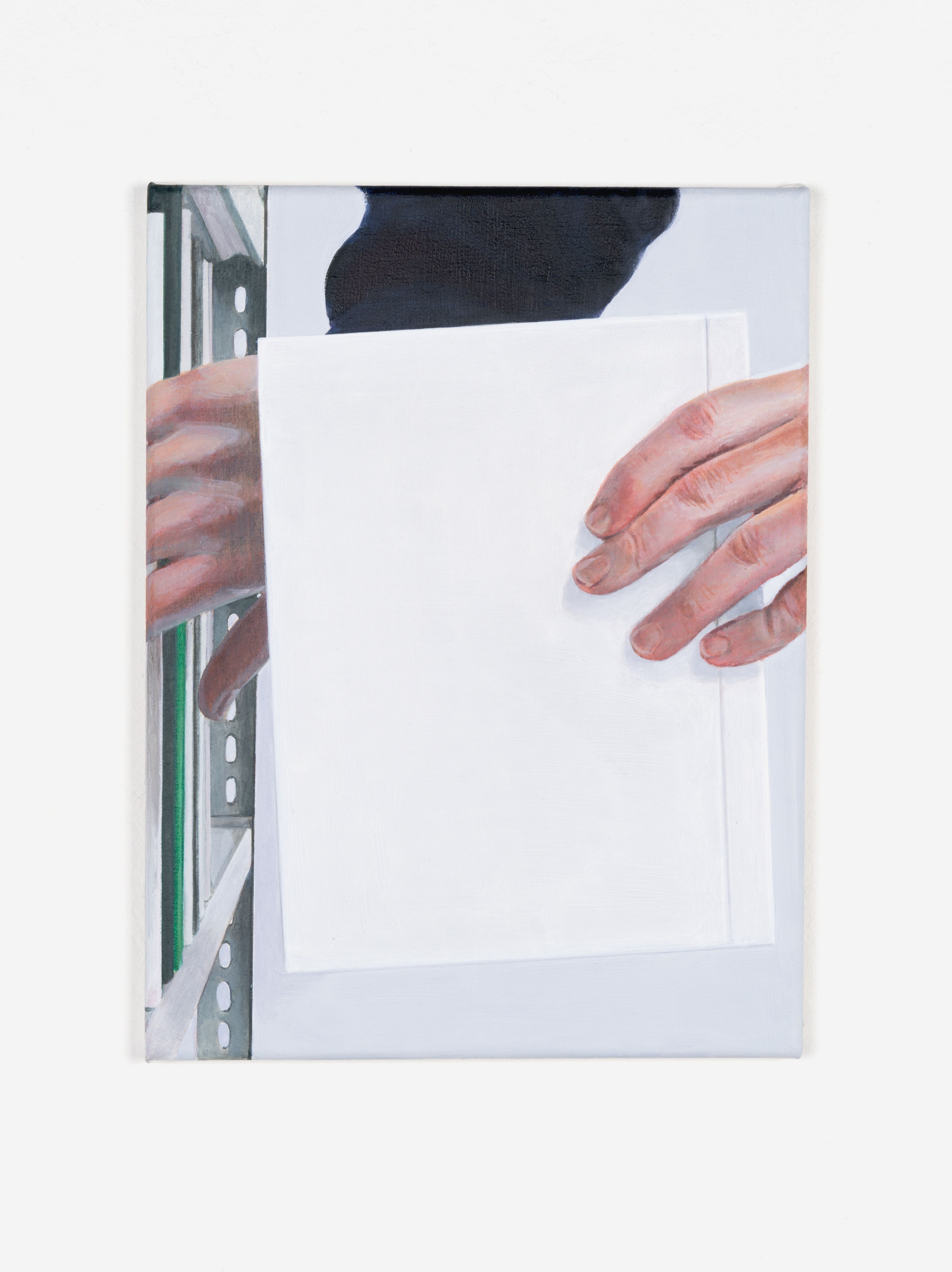

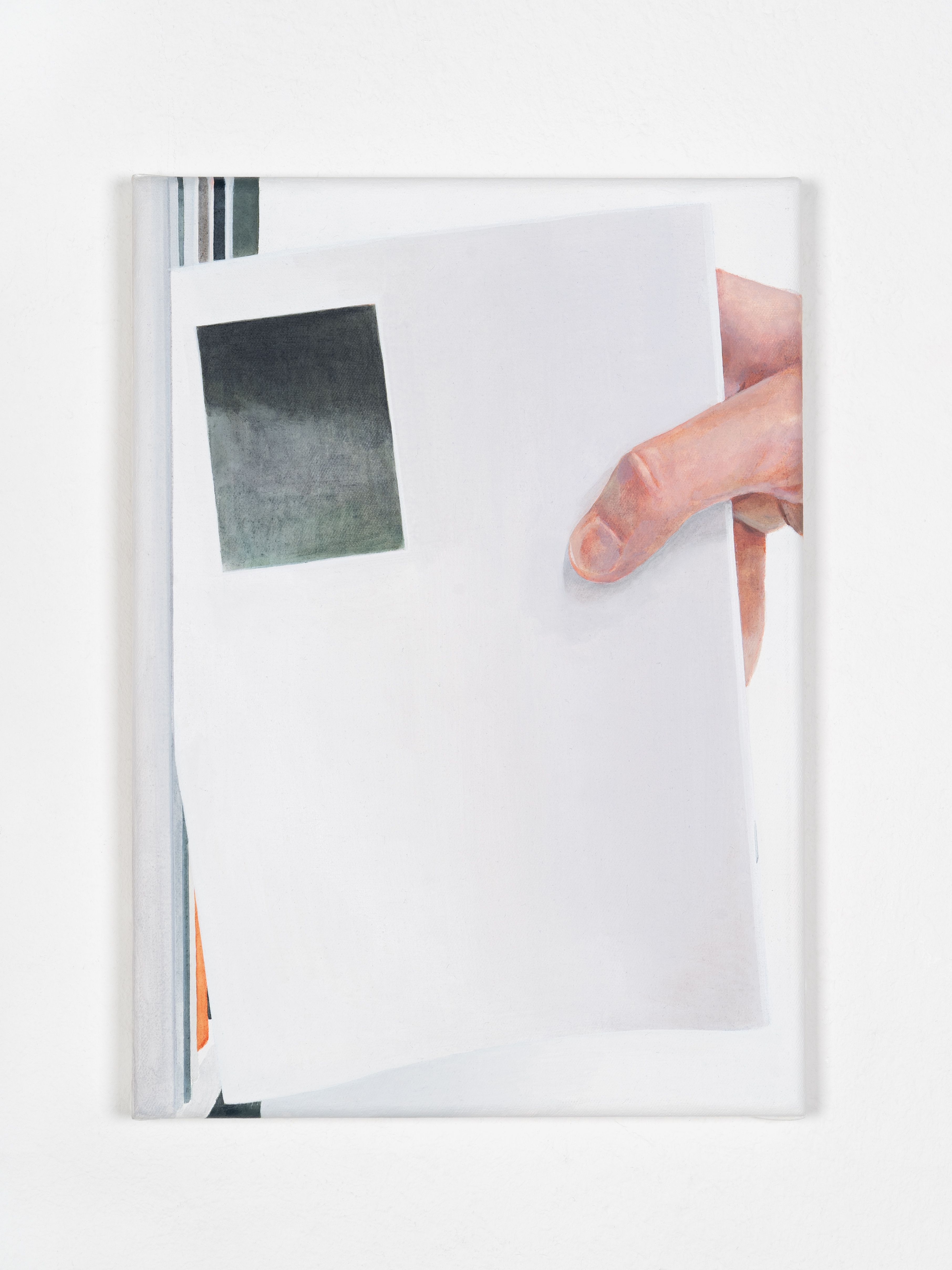

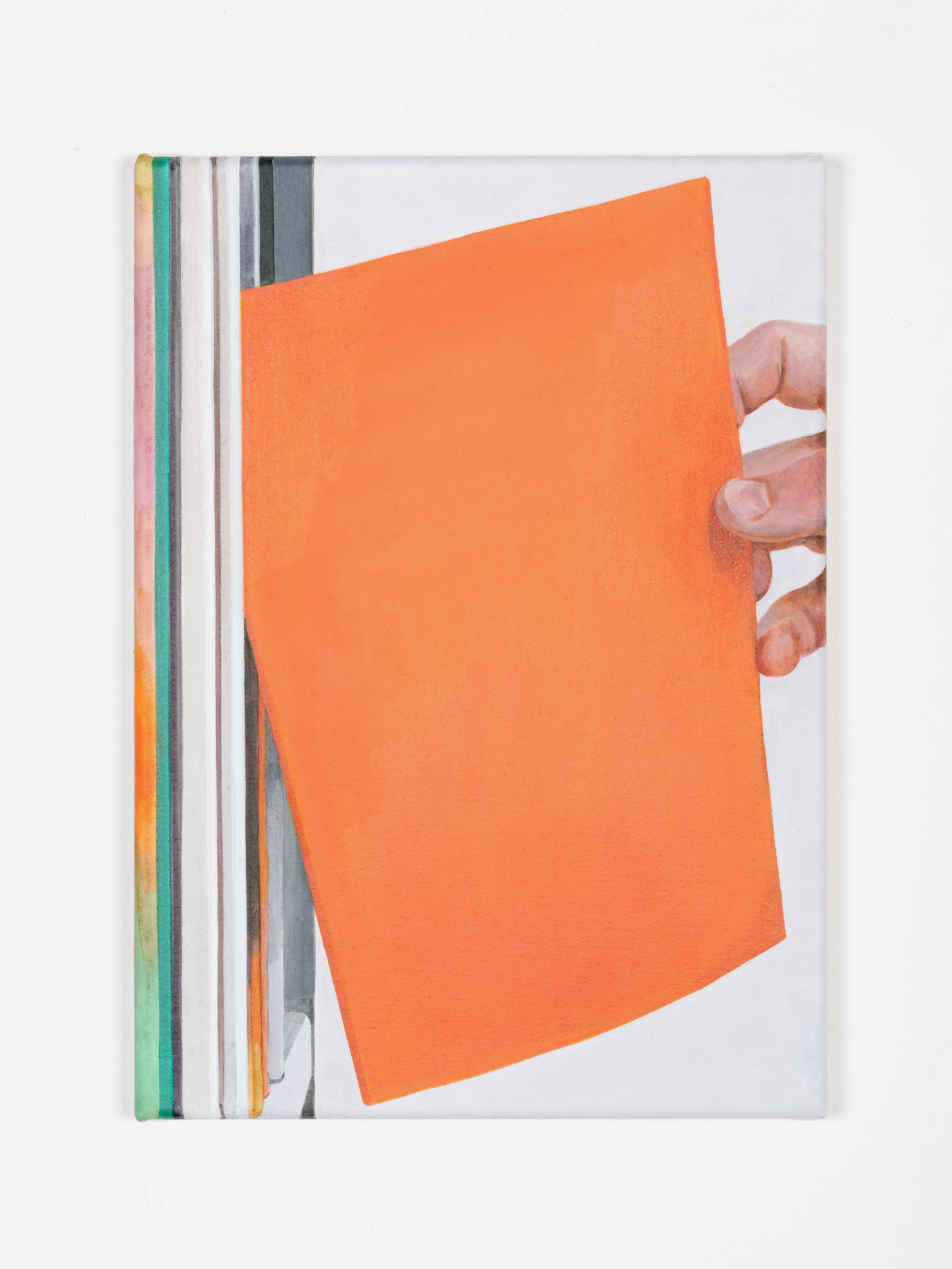

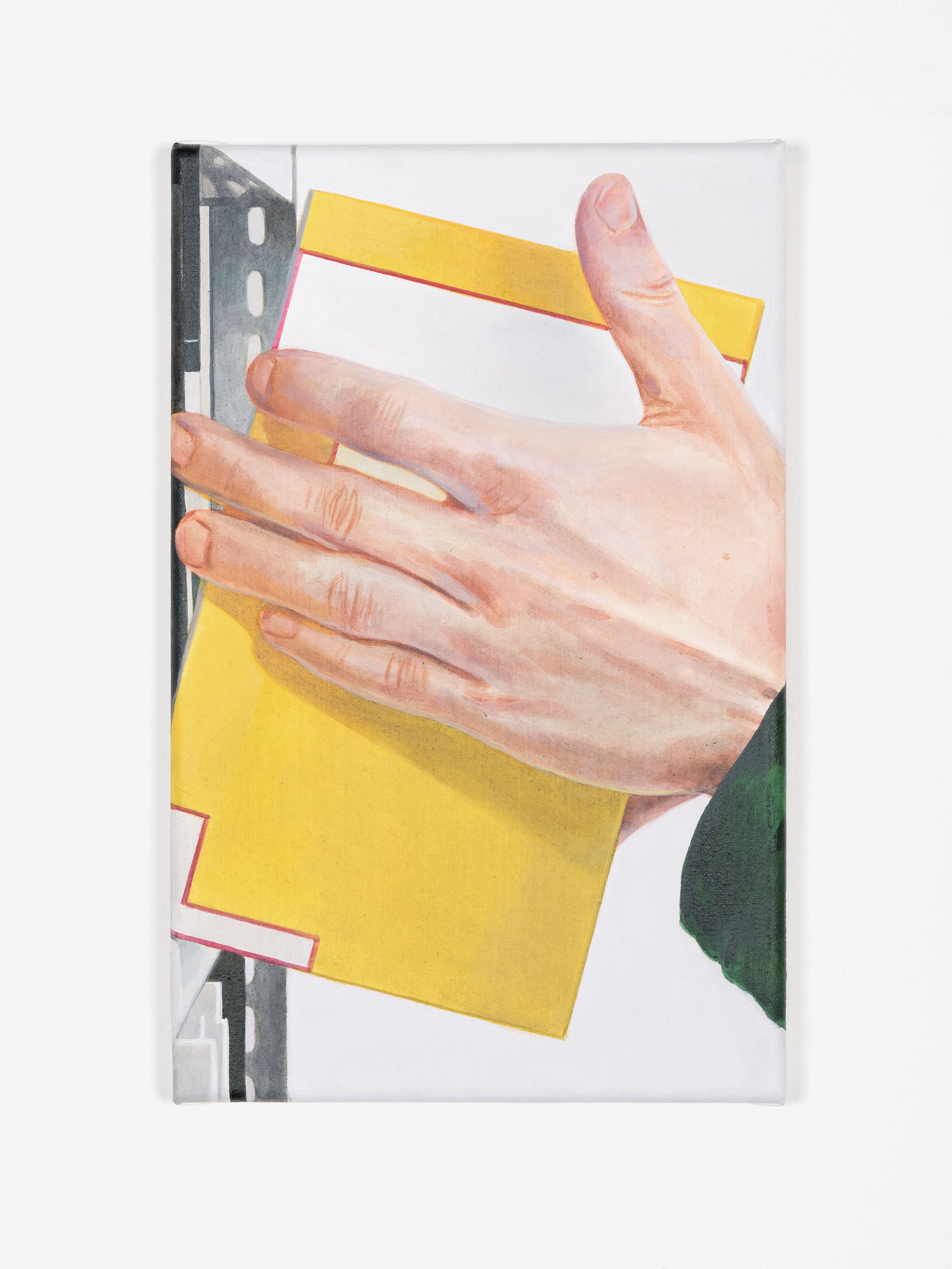

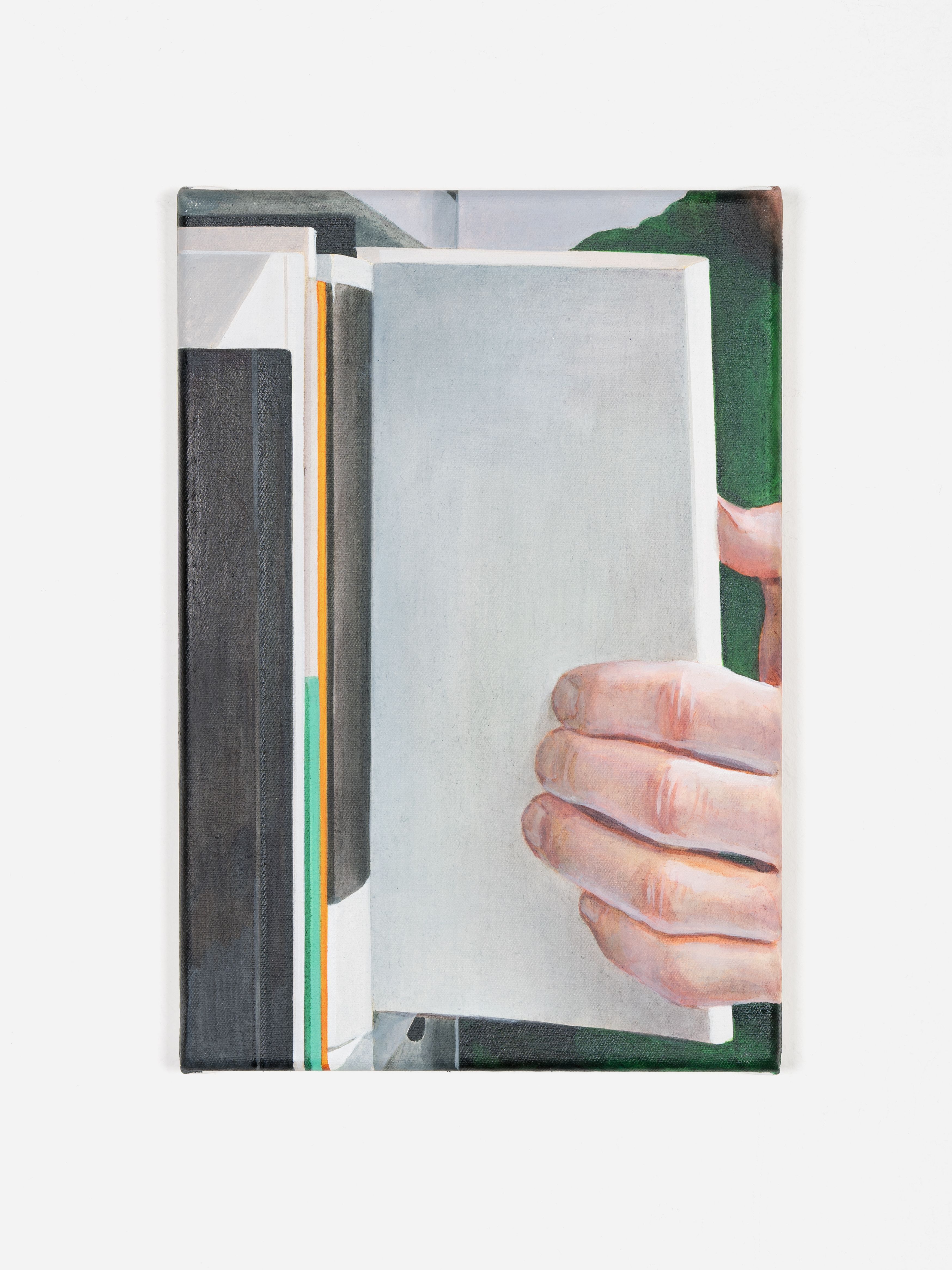

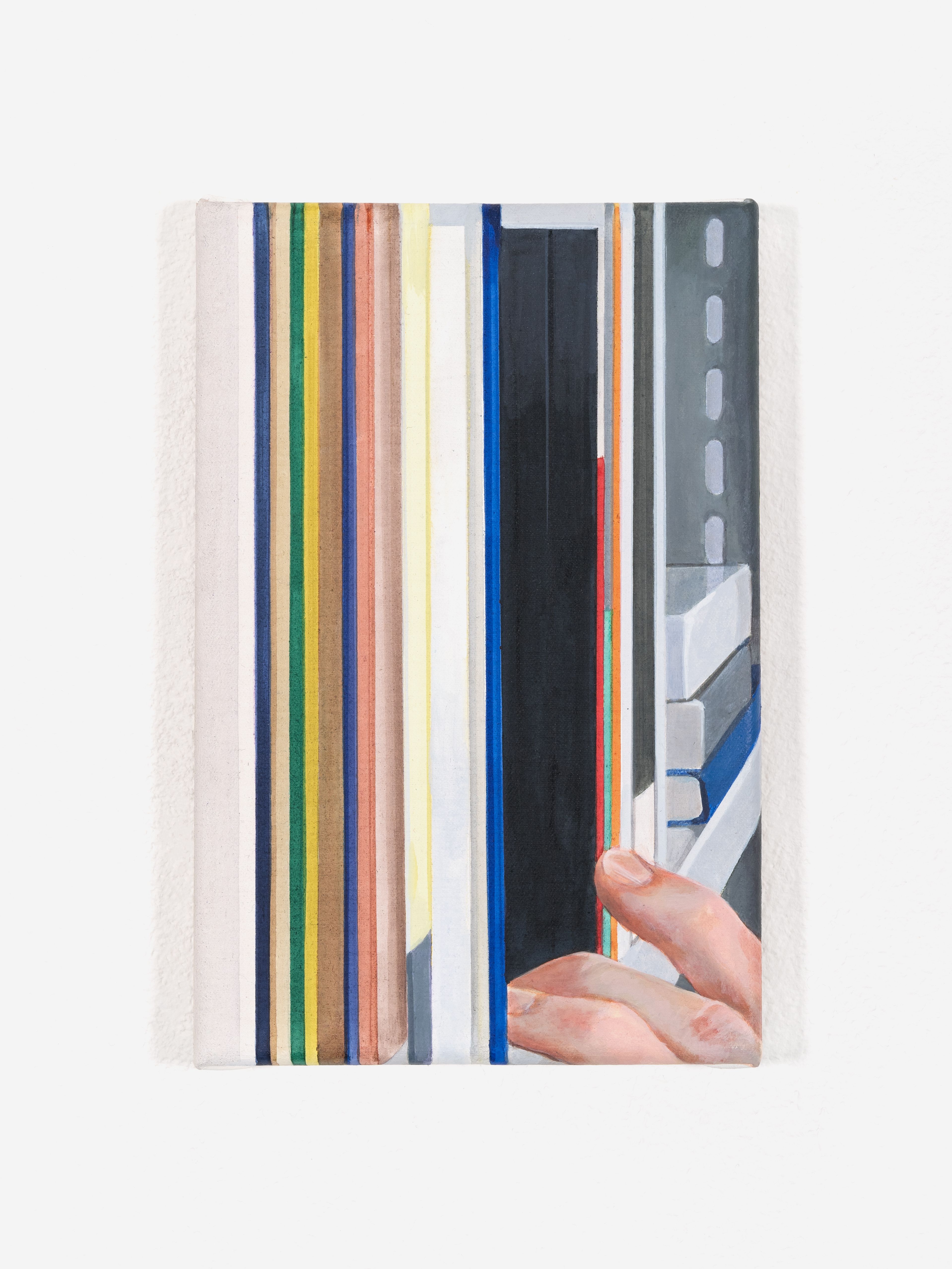

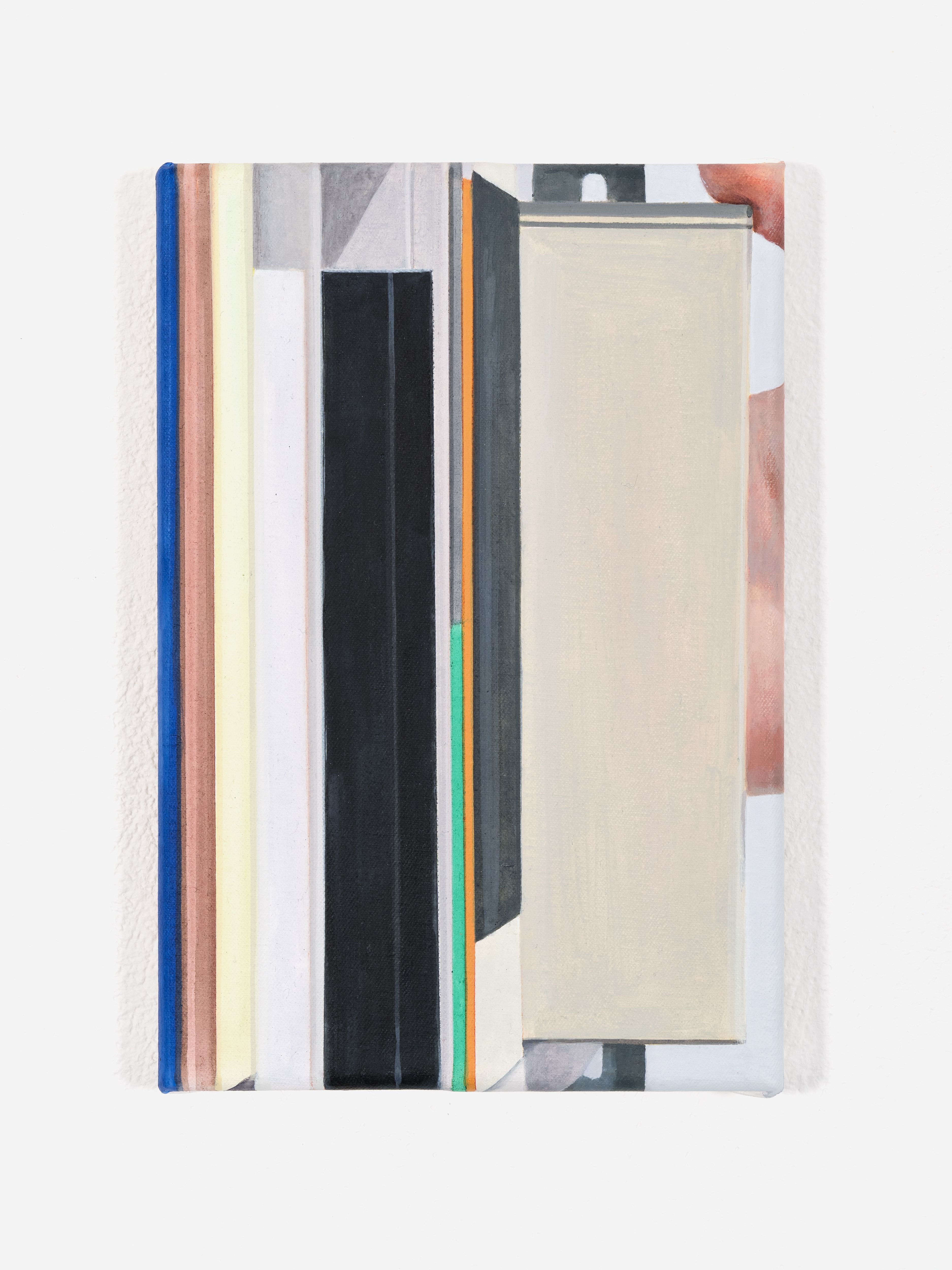

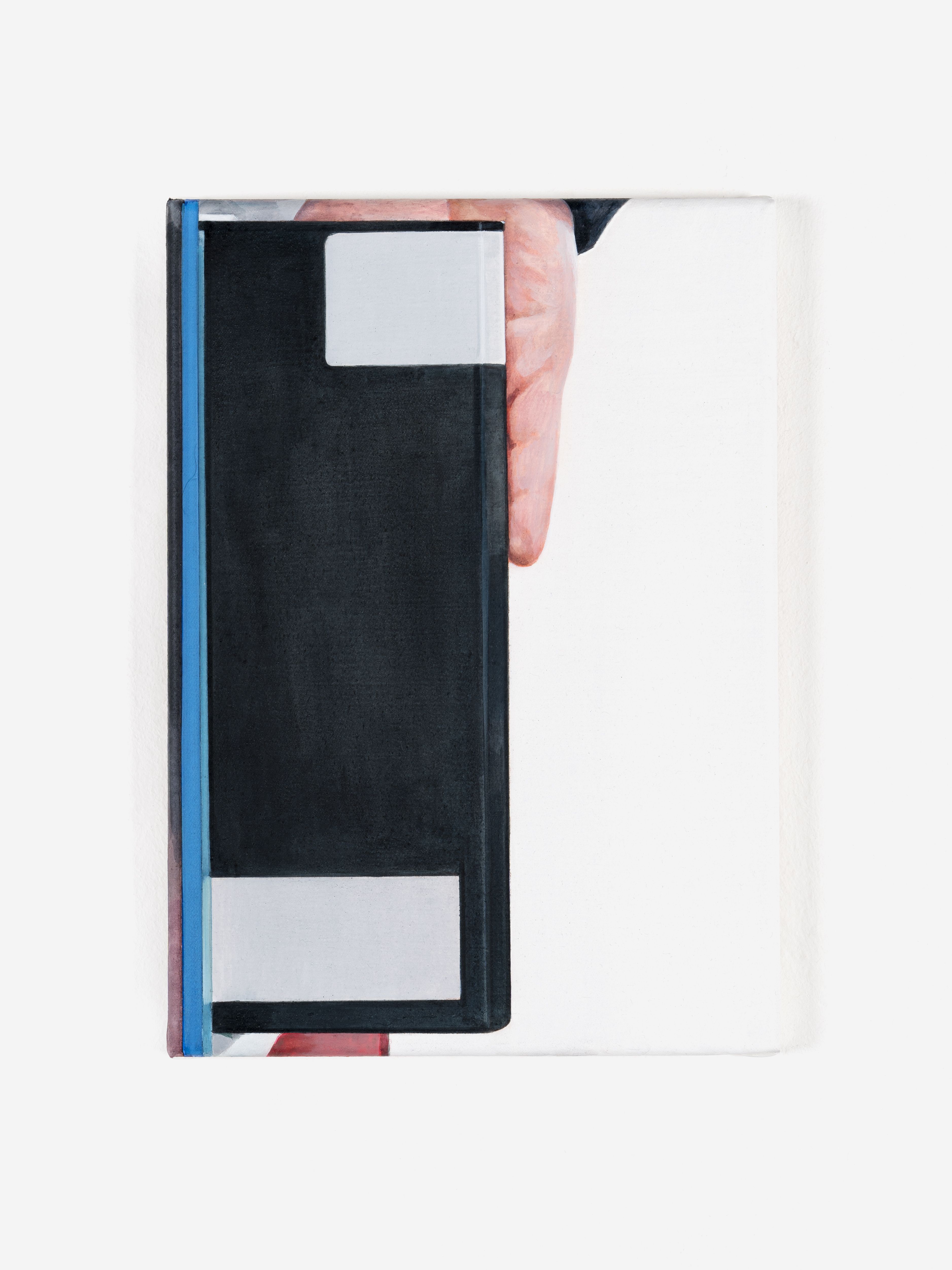

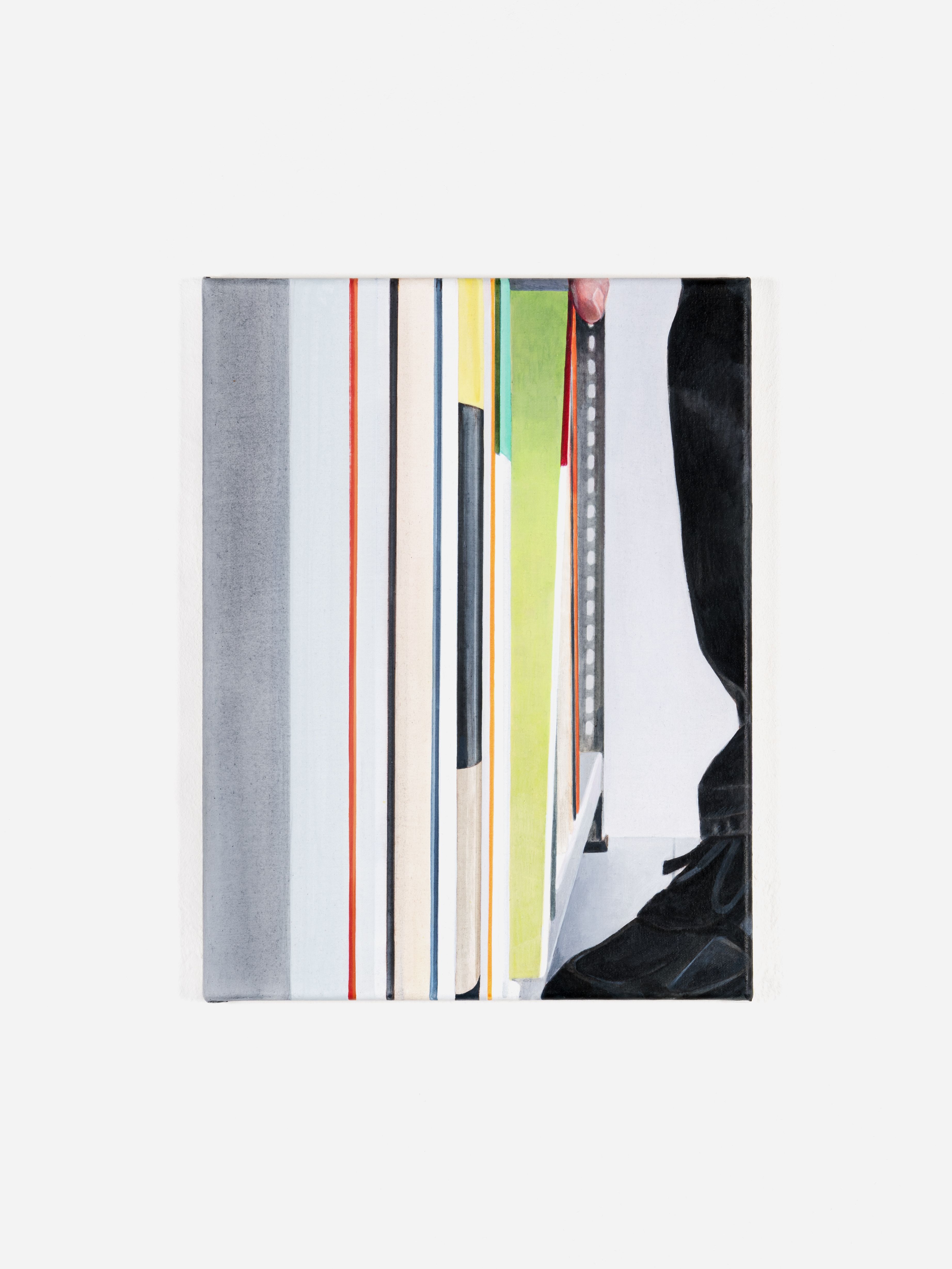

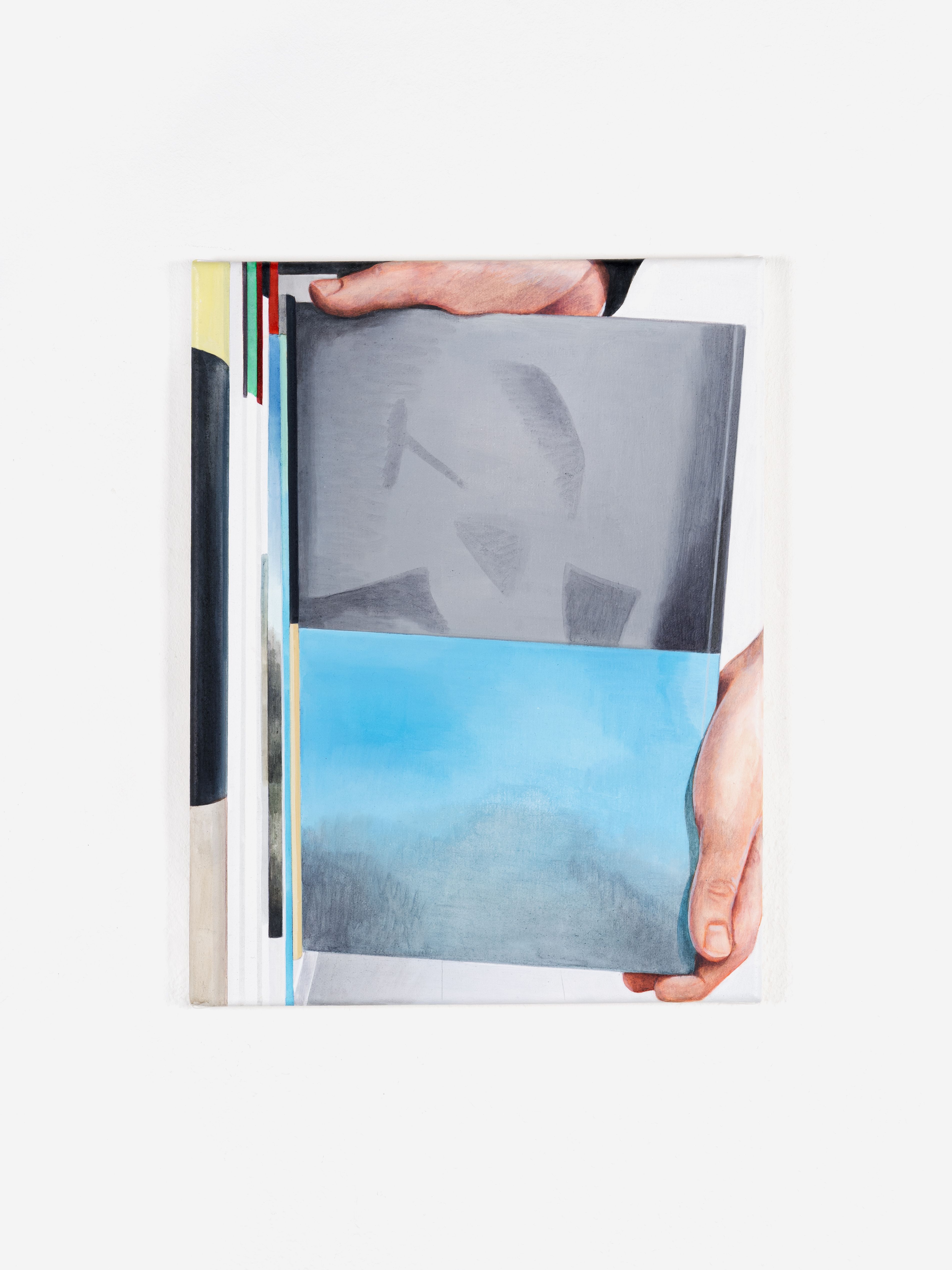

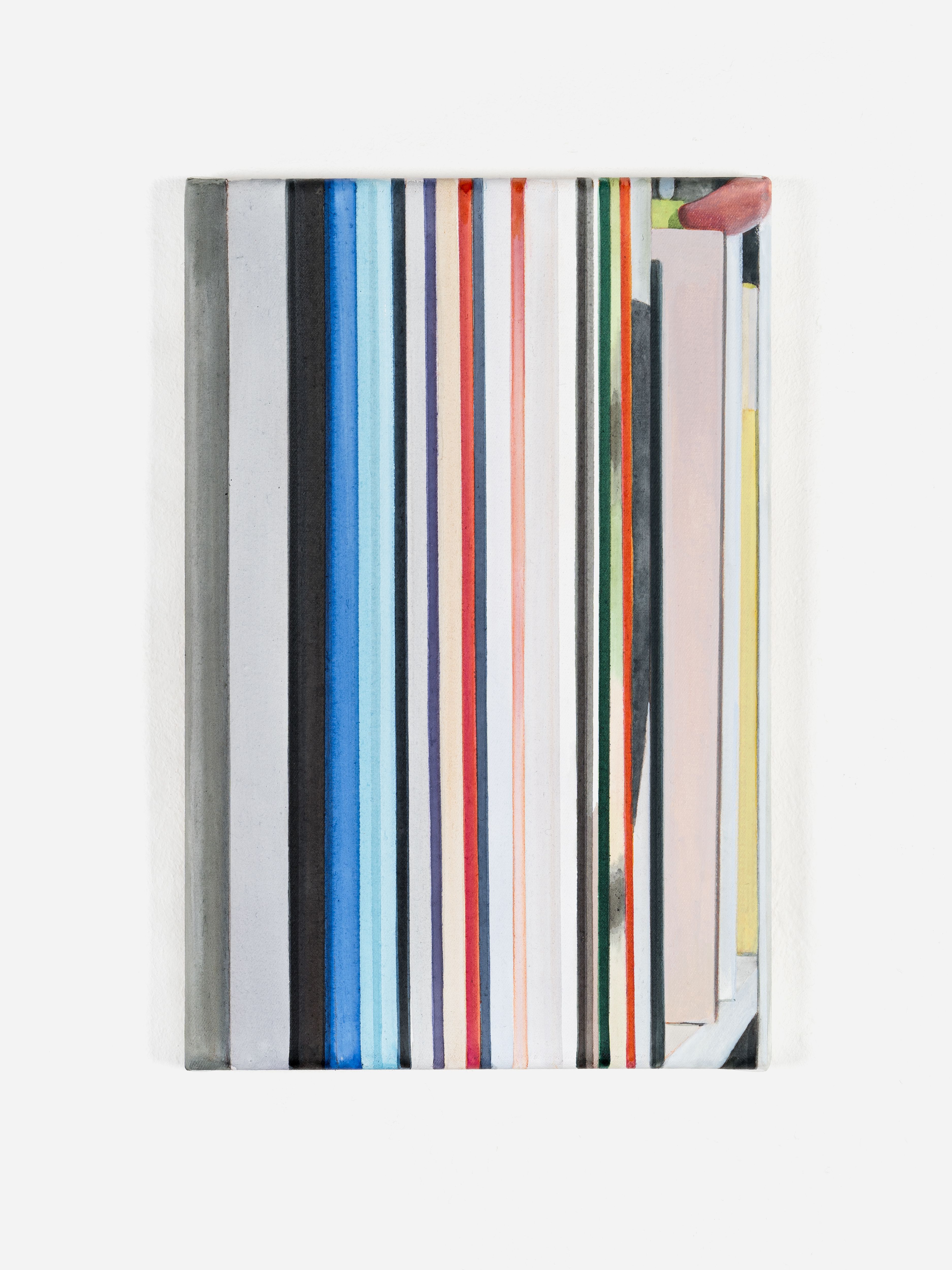

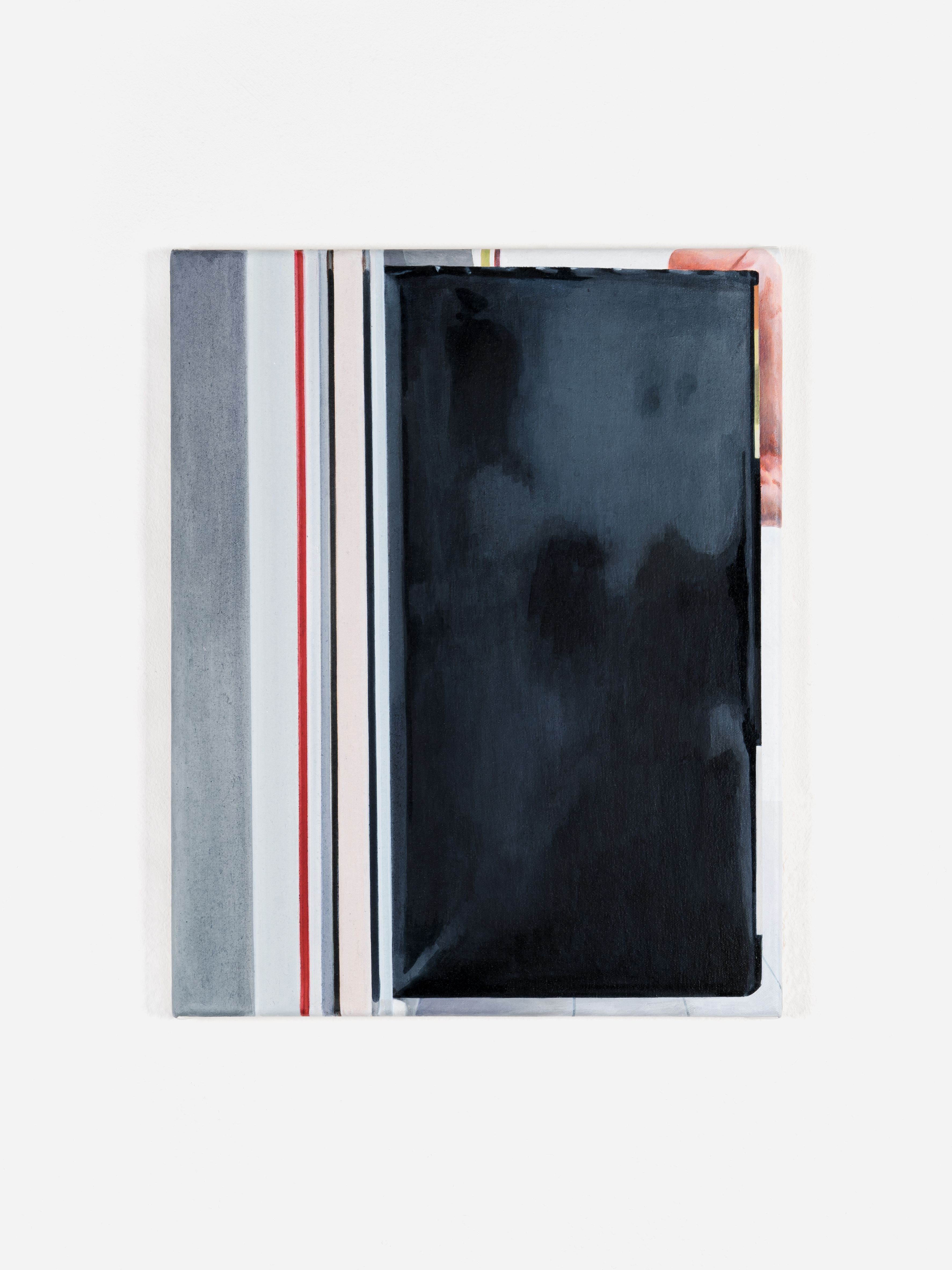

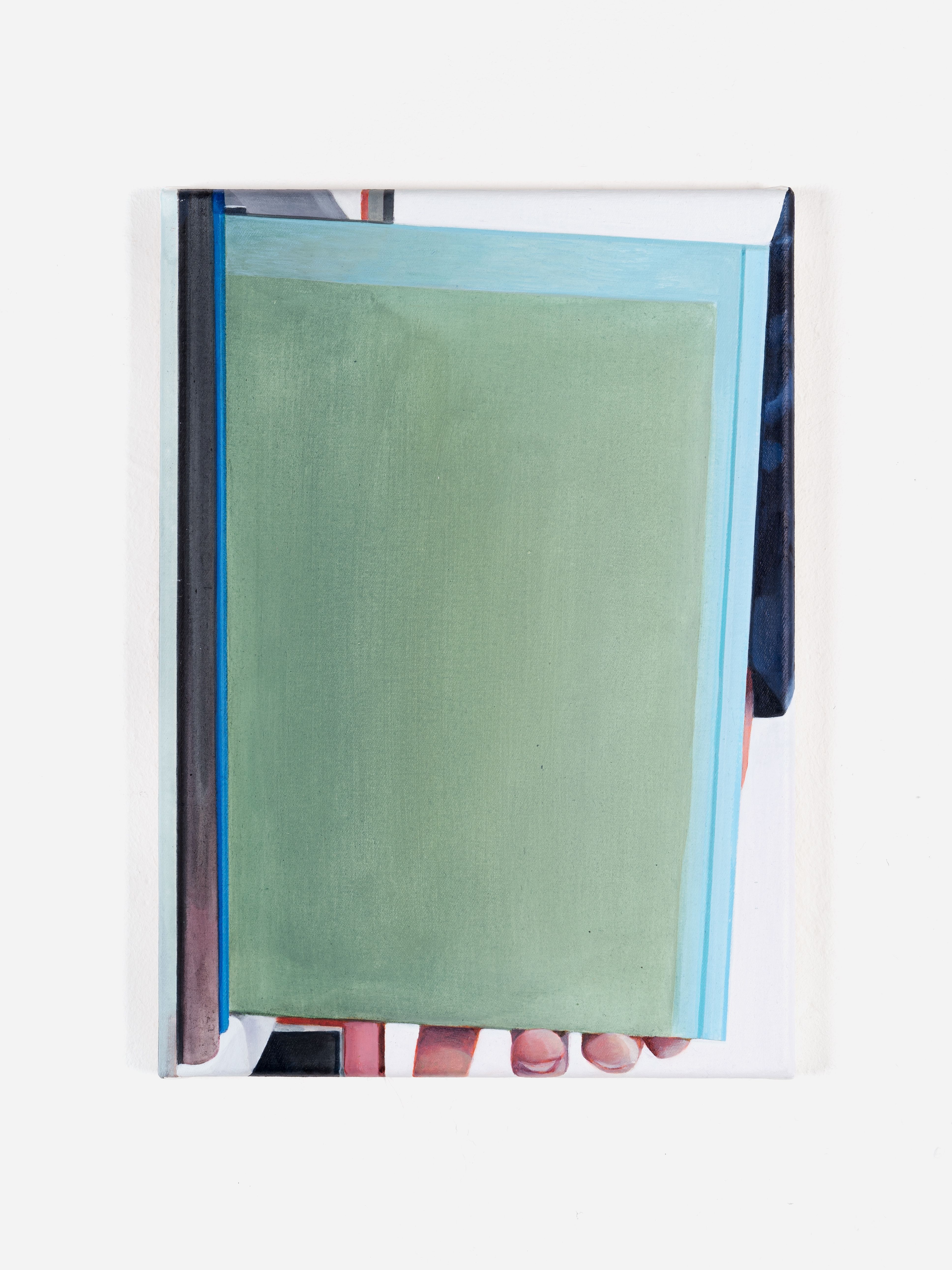

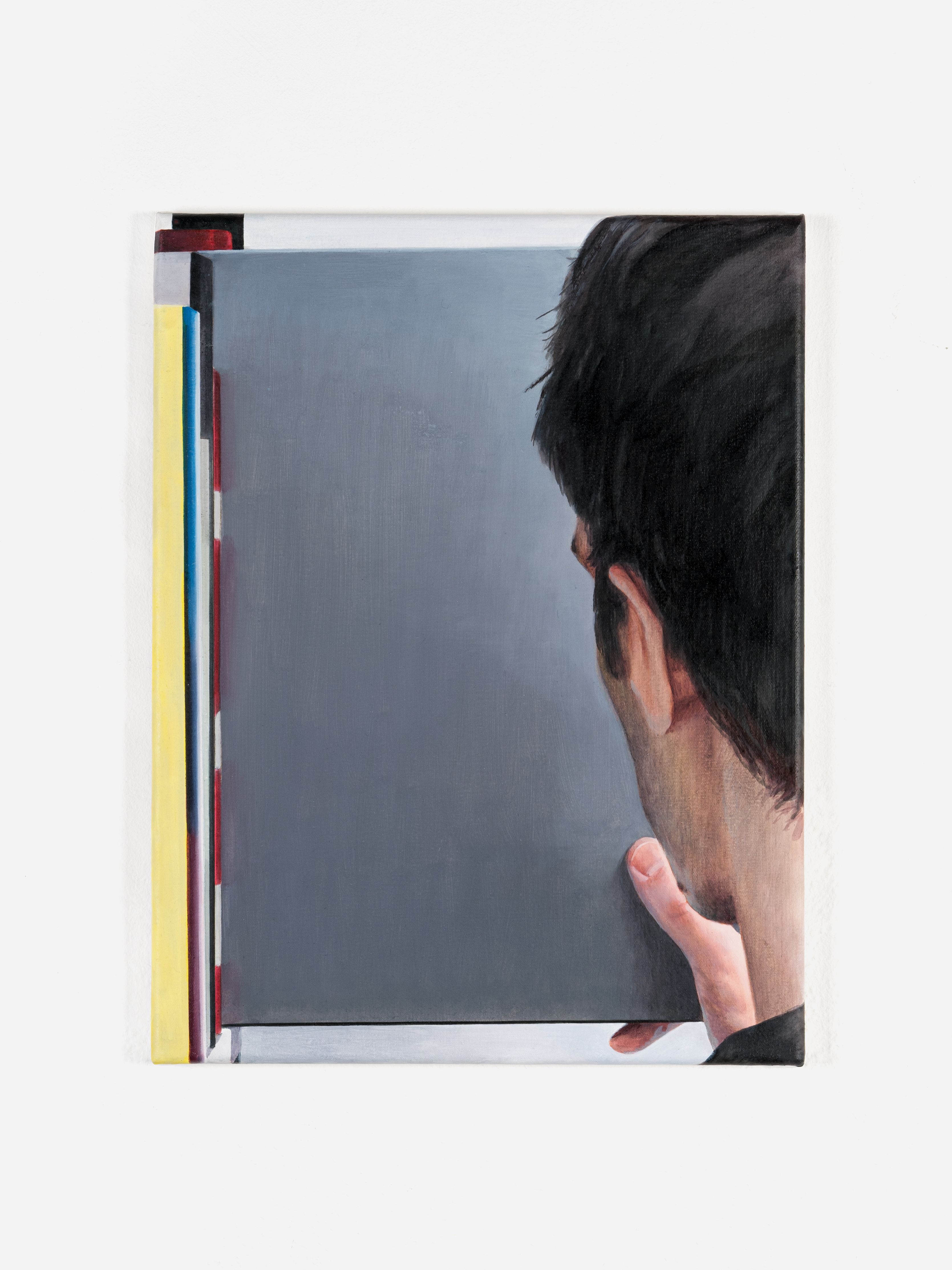

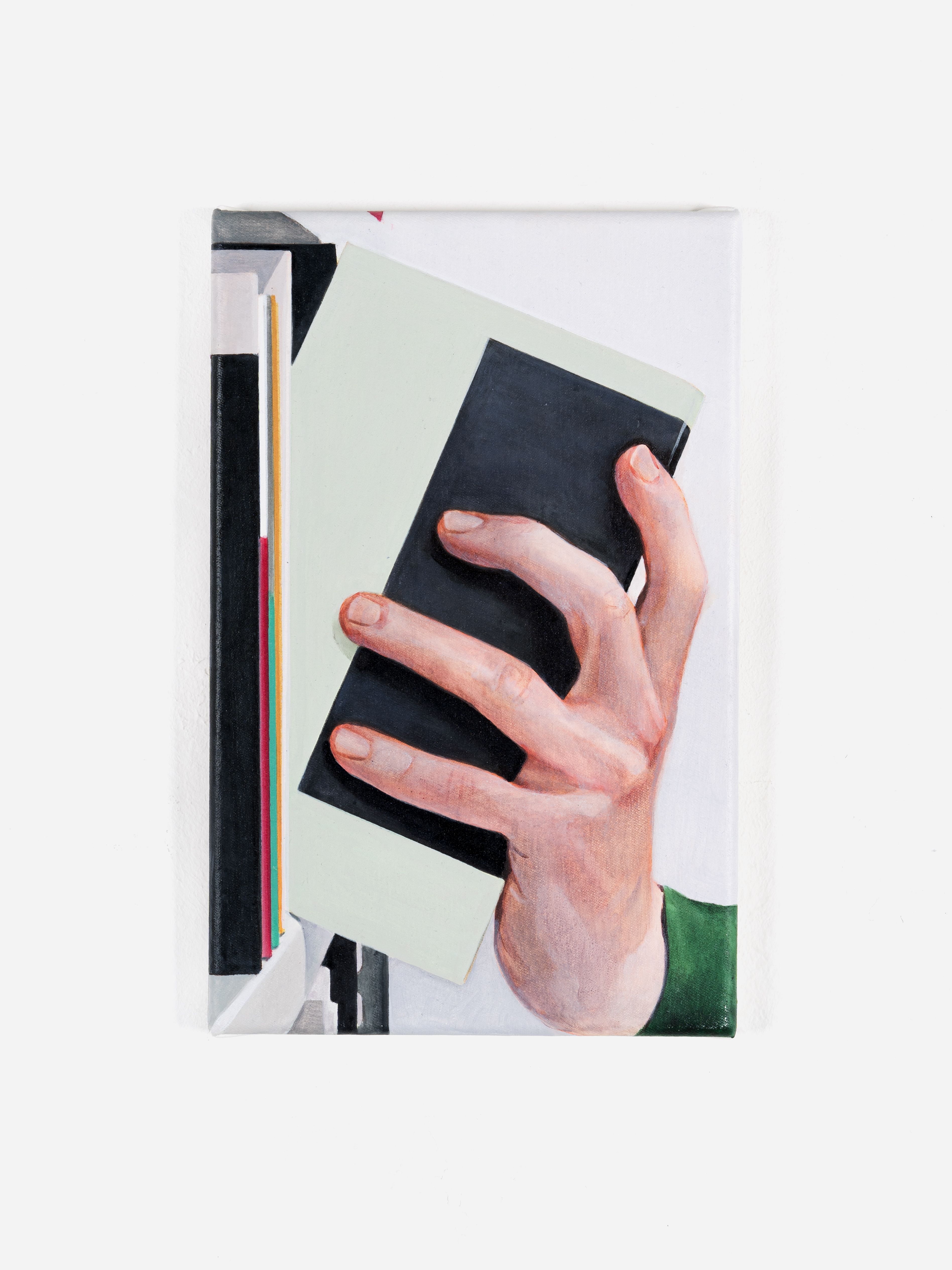

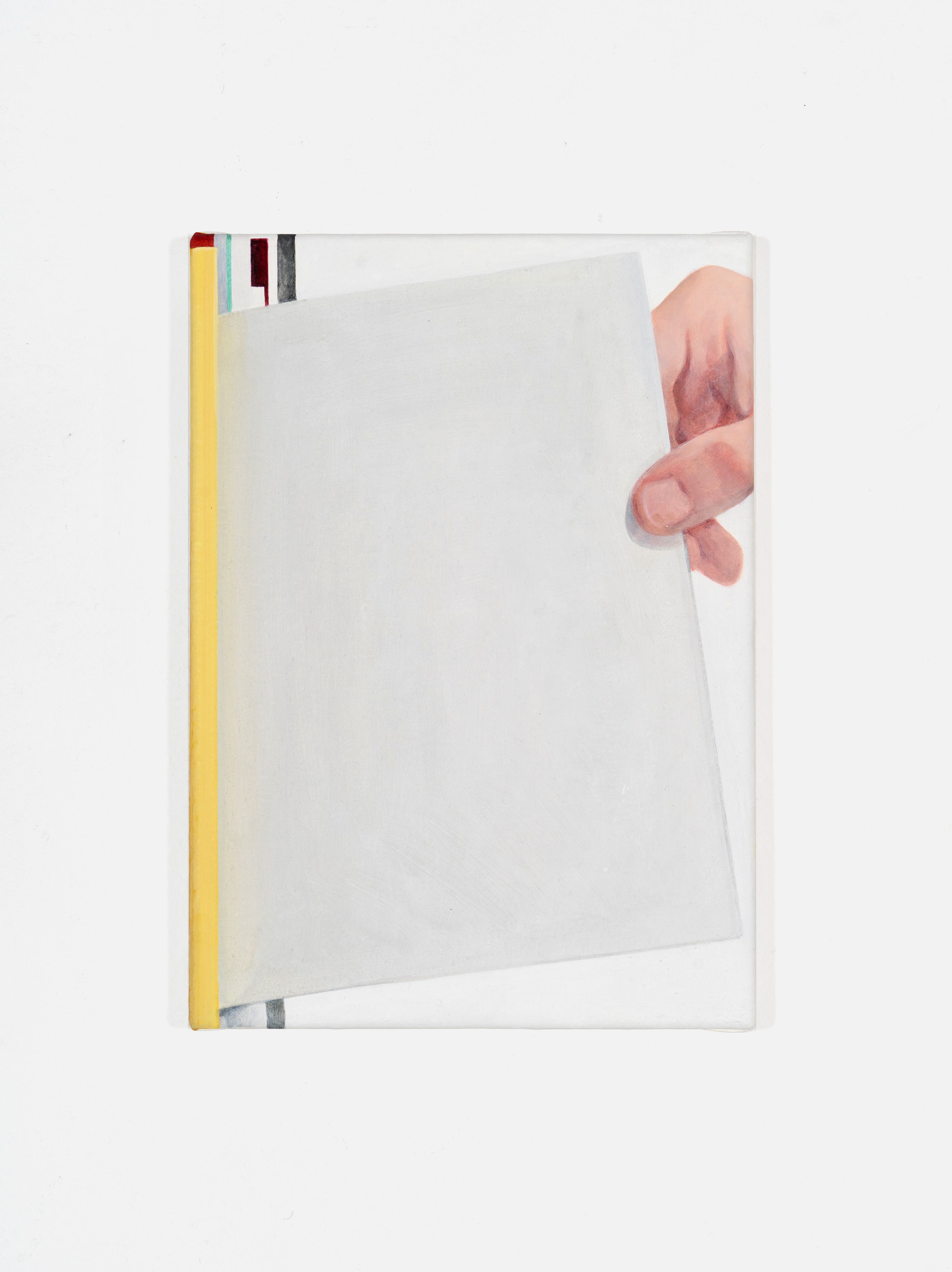

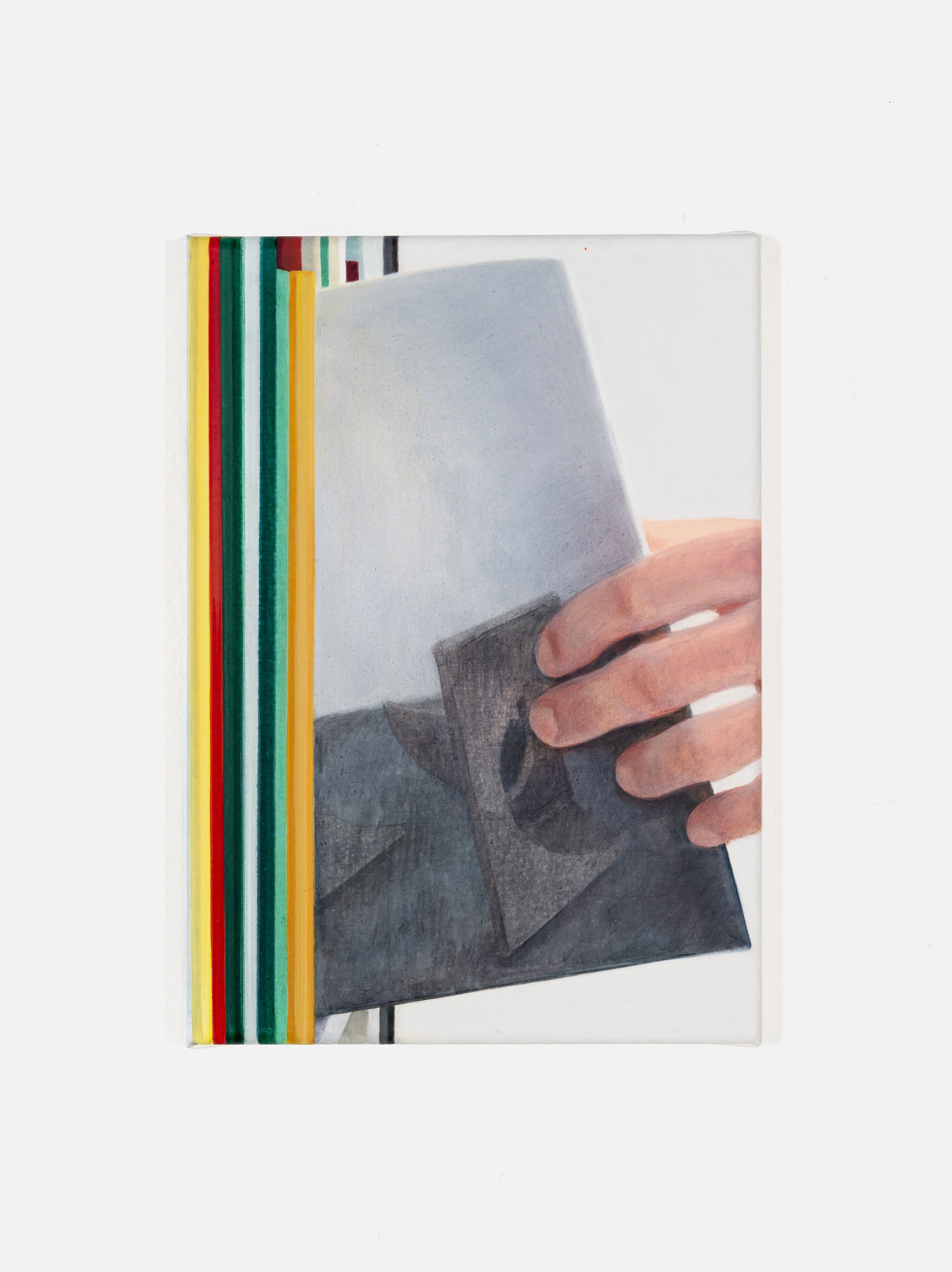

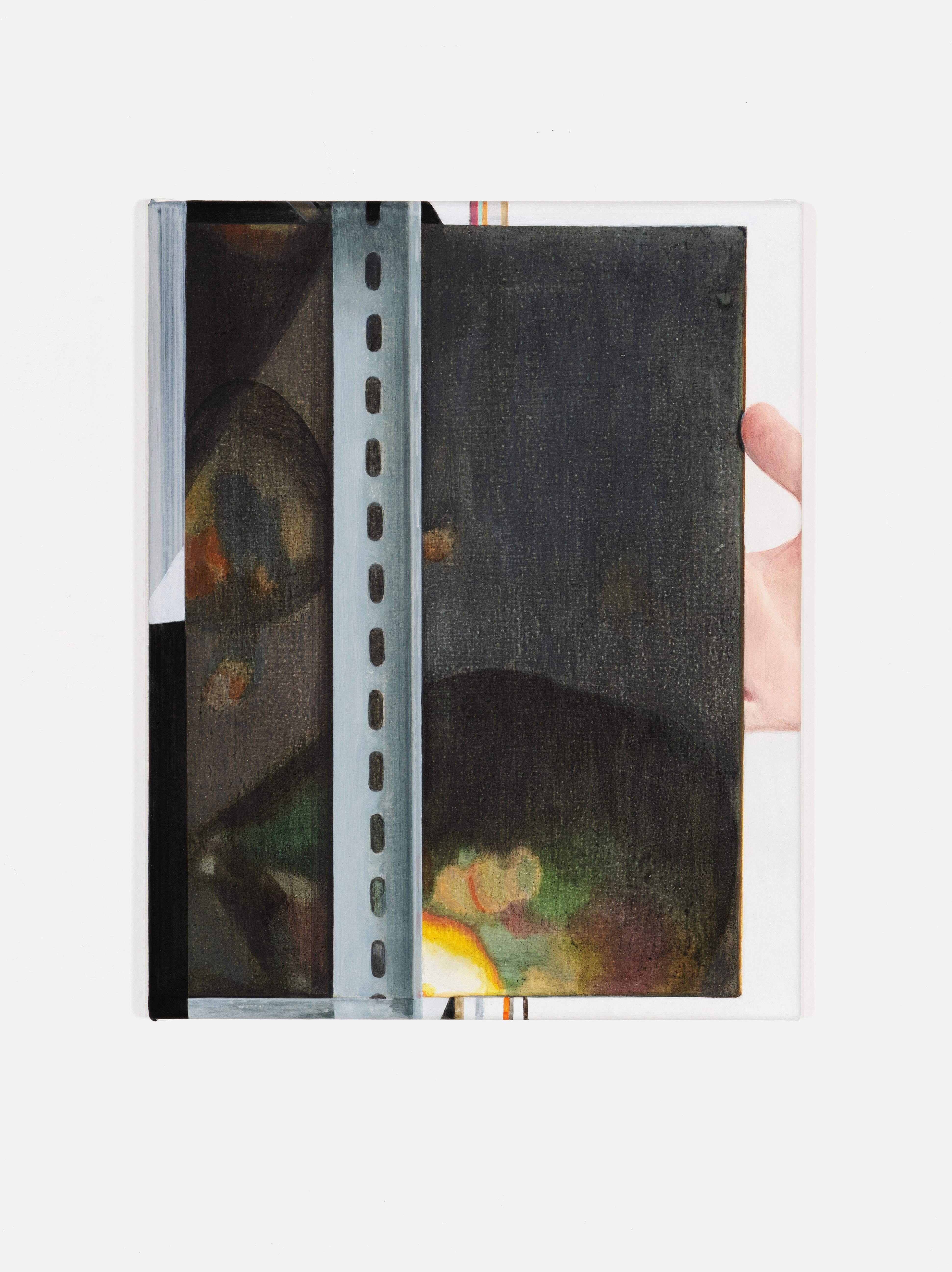

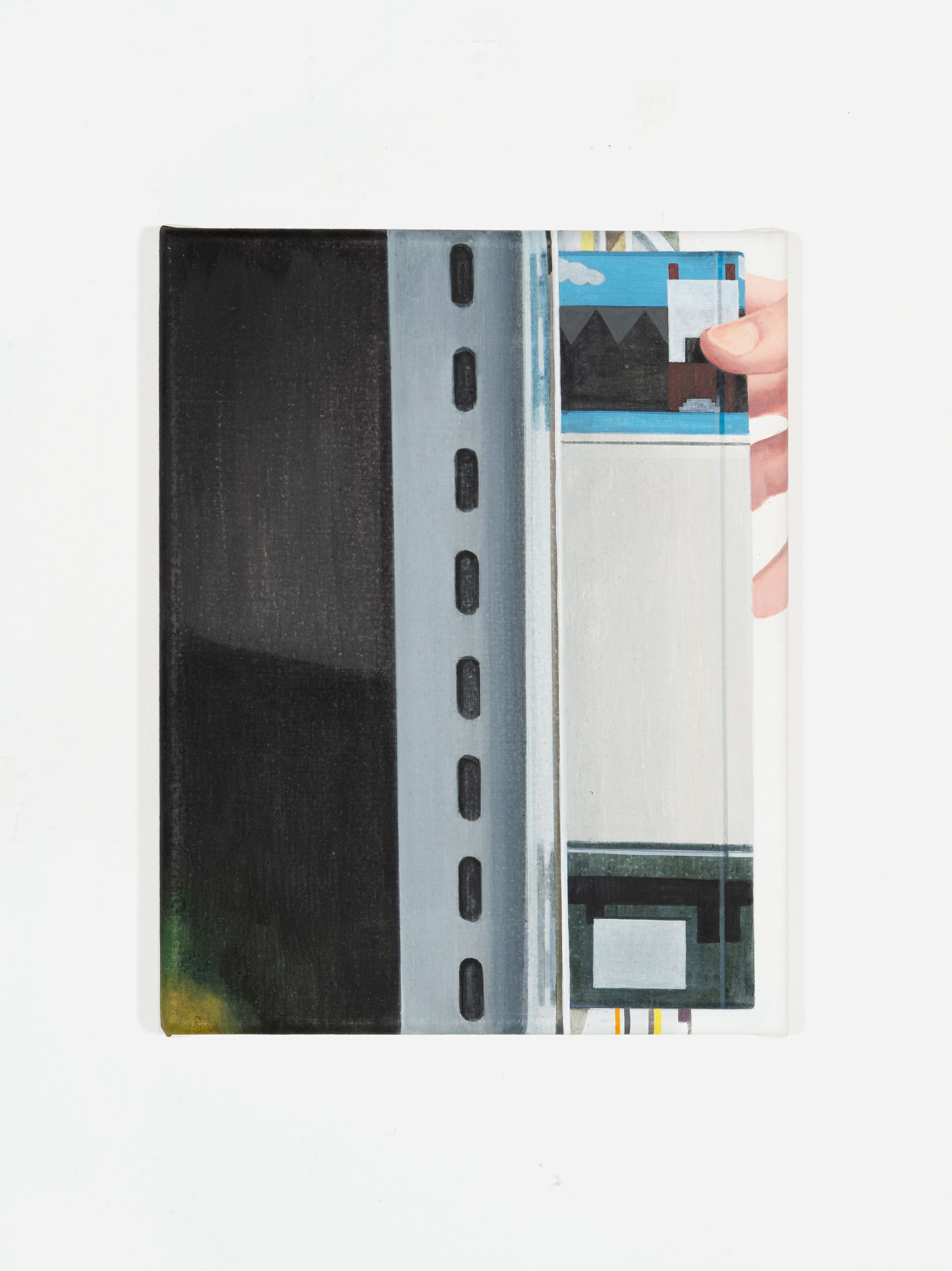

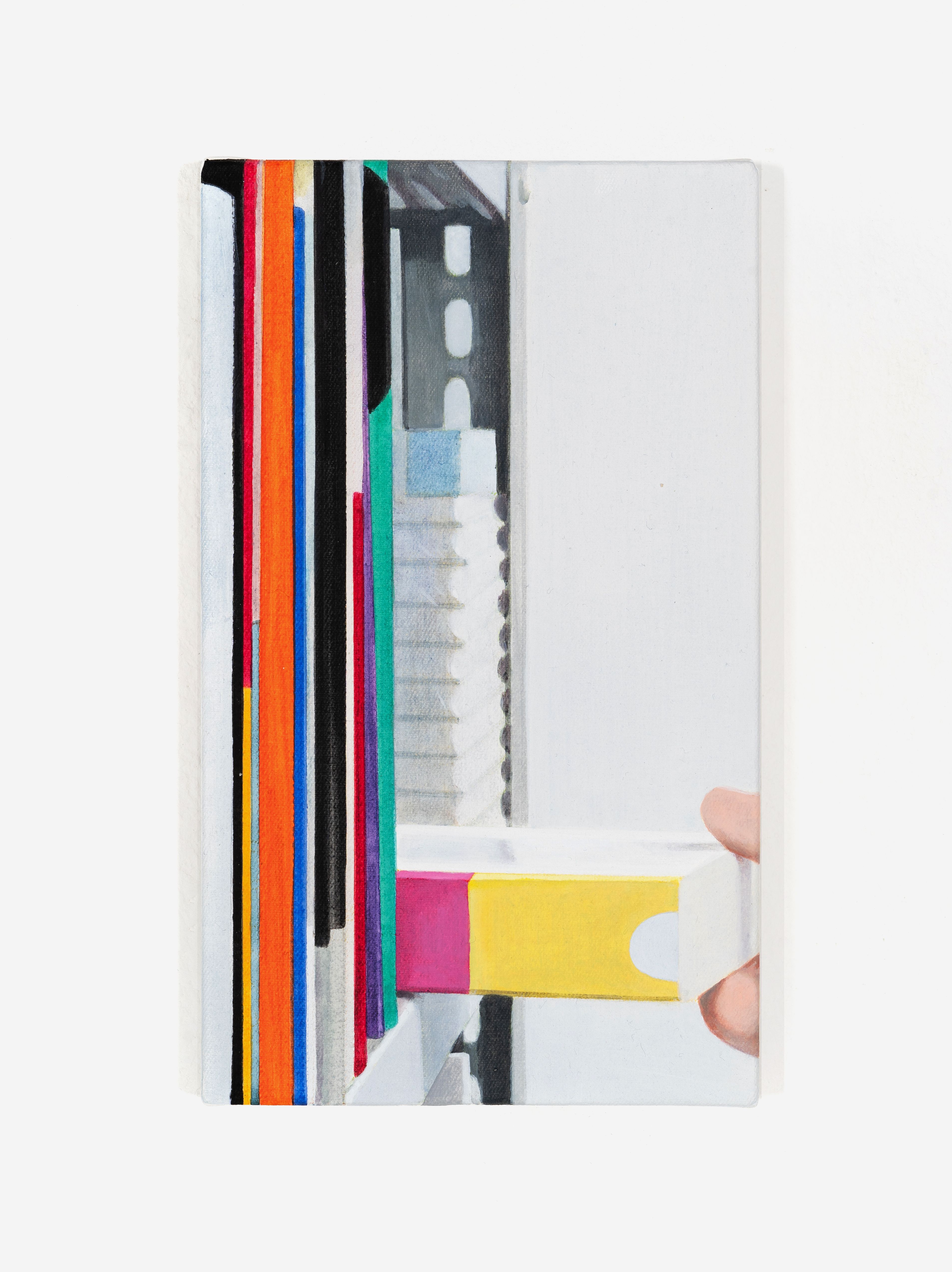

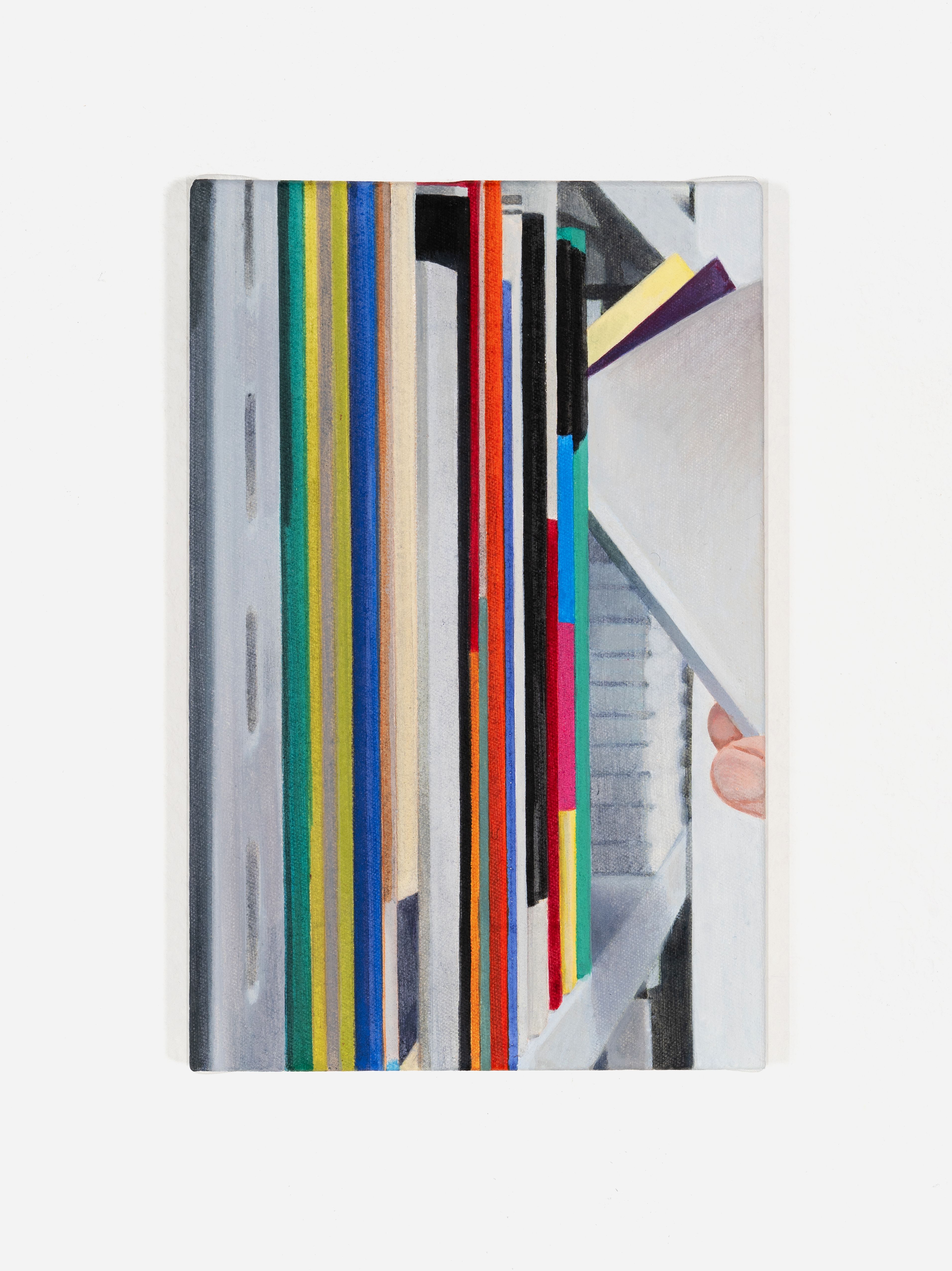

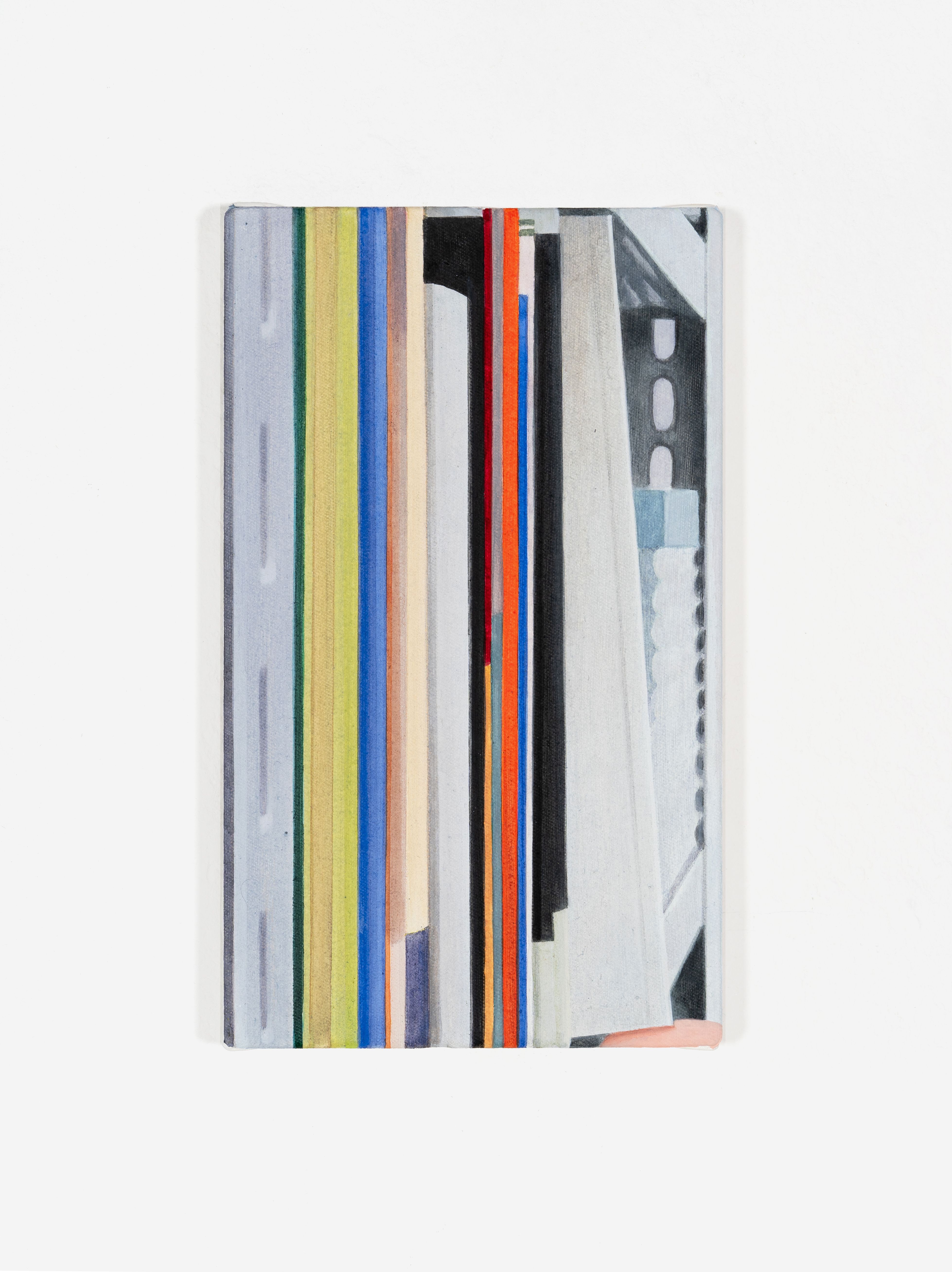

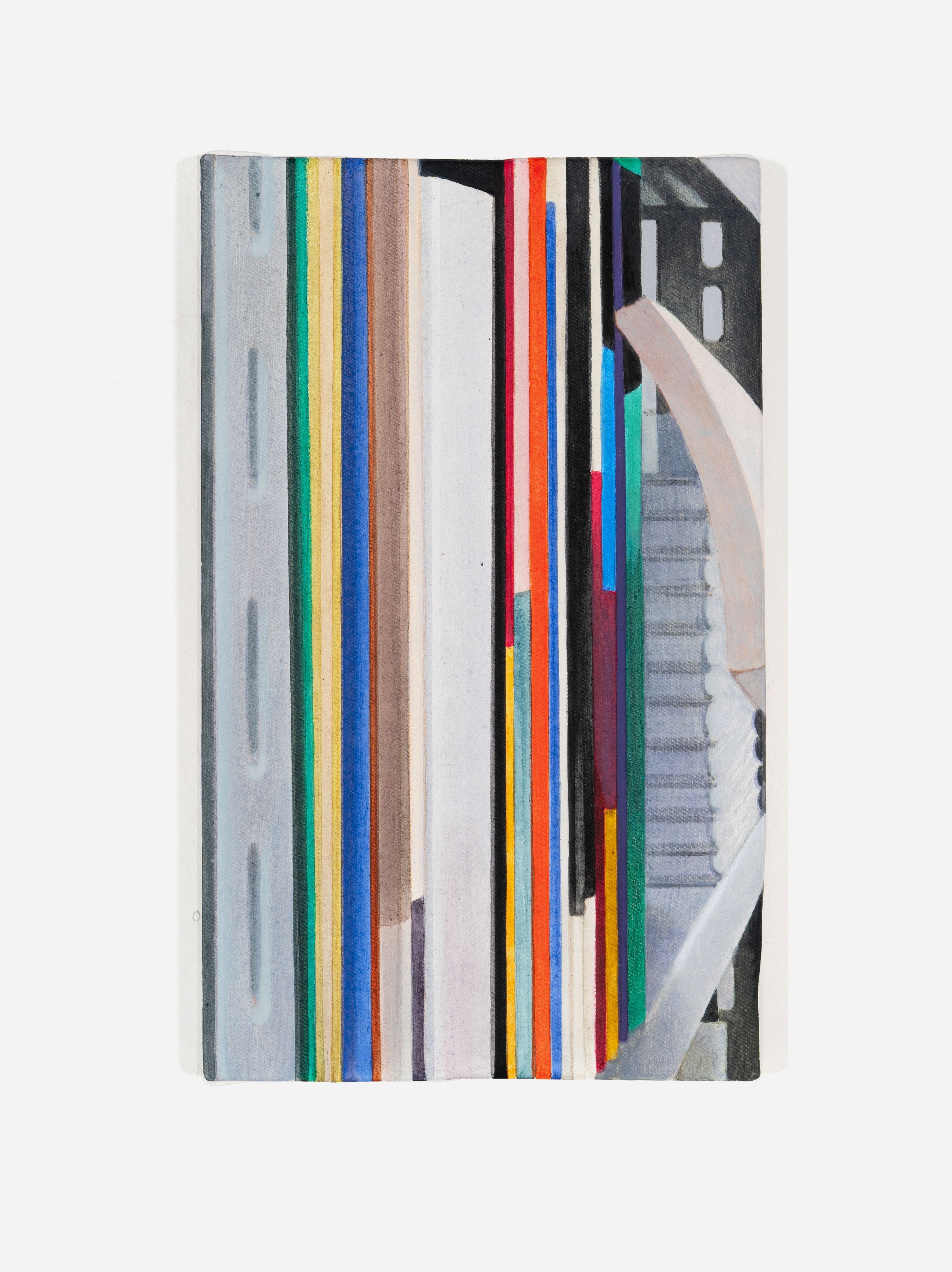

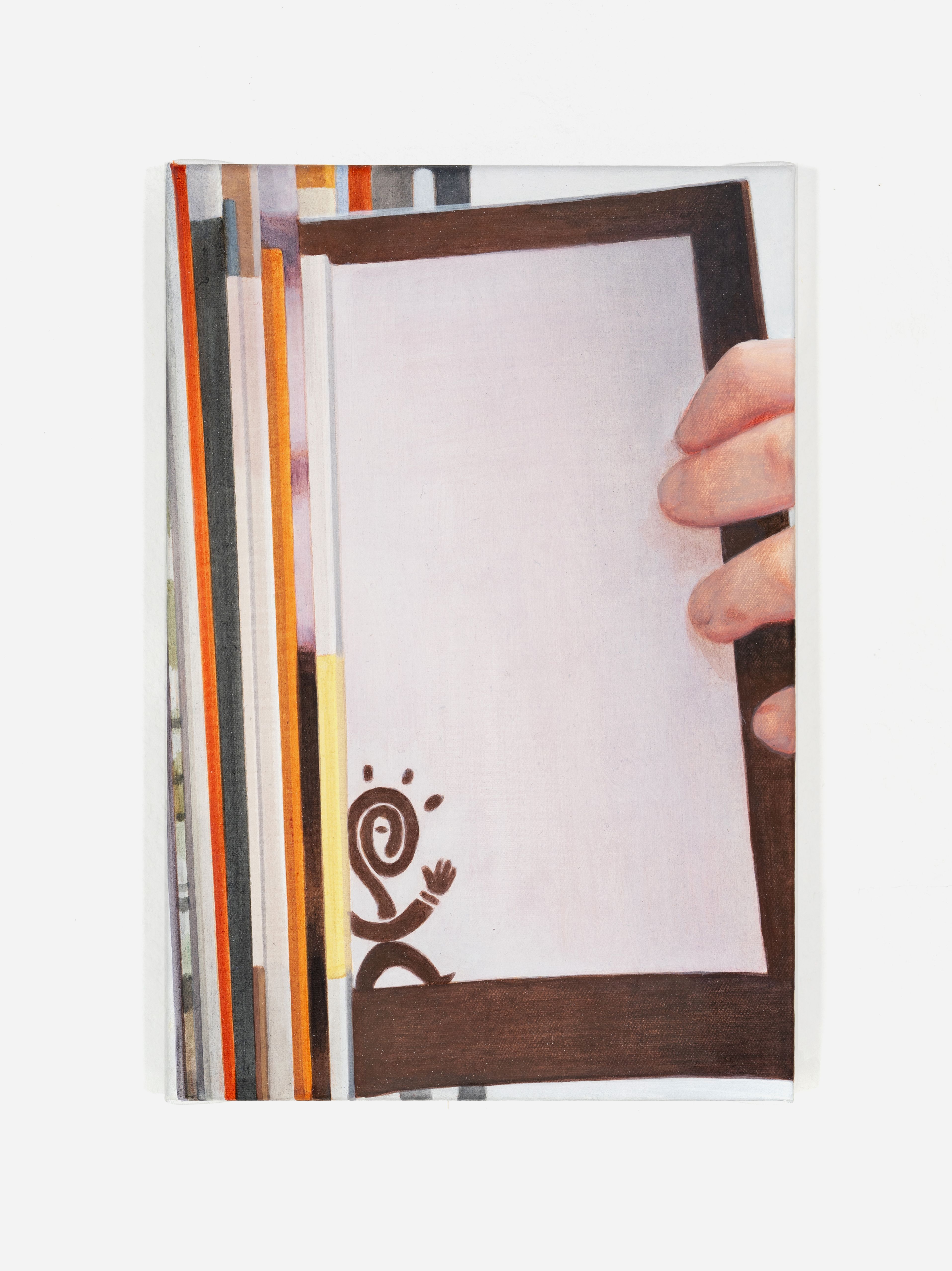

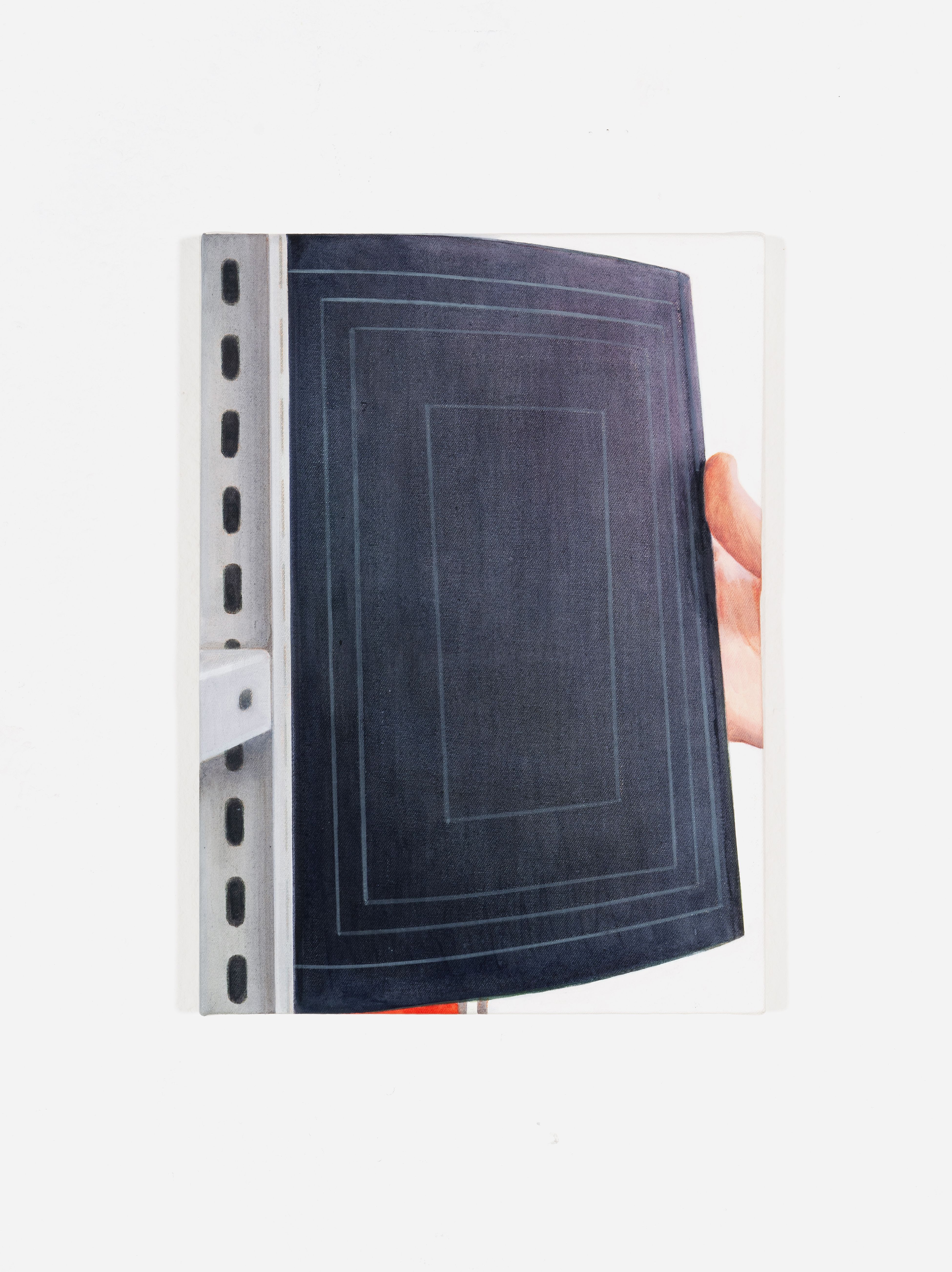

Each image in the 'A—Z' series shows a book being taken off a shelf or put back in by a hand or a pair of hands. The bookcovers are predominantly monochrome. They show neither text nor images. The position and gesture of the hand differs from image to image. The aspect ratios and dimensions of the canvases relate to the books depicted, which means that the paintings in the series slightly differ from one another not only in their motif, but also in their format.

All 90 works: Untitled, 2021, acrylic on canvas, formats vary from 21 × 13 cm to 40 × 51 cm

Book

Image Runner

The two-part publication 'Image Runner' was published by Hammann von Mier Verlag to accompany the eponymous presentation in the Galerie der Künstler:innen in 2020. The image part (open thread binding, 152 pages) includes 92 sheets taken from a larger body of work and created between 2017 and 2020. The accompanying brochure (stapled, 16 pages) contains the text 'Man in office making copies using photocopier' by curator Juliane Bischoff and a list with details about the production of each sheet. Both parts are printed in 4/4c offset and measure 24 × 32 cm each. The text part was designed by artist and graphic designer Jan Erbelding. The production of the publication was supported by the LfA Förderbank and the Free State of Bavaria.

006

Grid Comforts

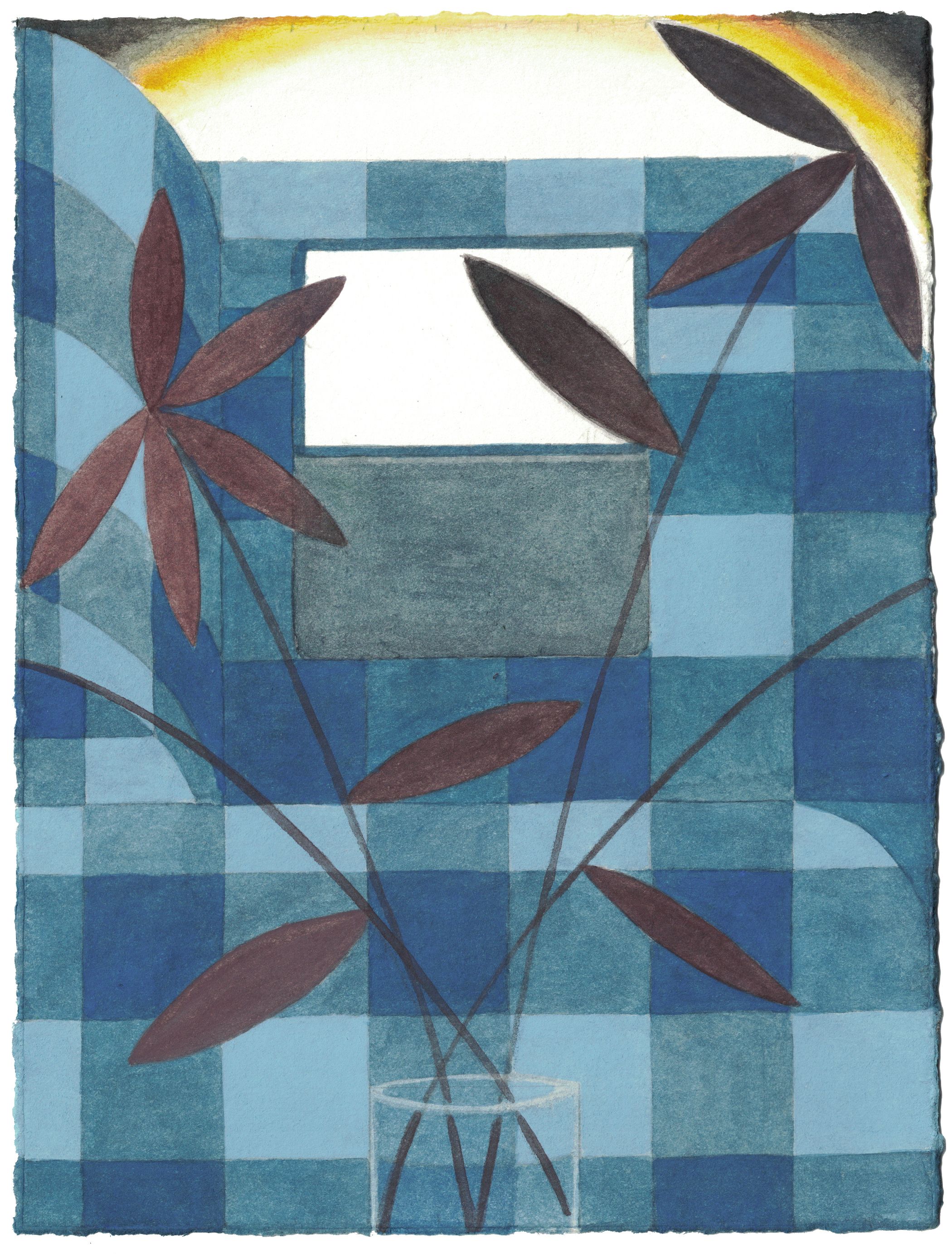

The images in 'Grid Comforts' each show a bird's eye view of a figure and a laptop, which I place on the grid of a patterned bedspread. The screens are blank or show an aerial view of the Californian island of Catalina, a pre-installed background image of the Apple operating system macOs. While the protagonist remains the same, both the lighting mood and the pattern of the bedspread change from picture to picture. This results in a number of different versions of the same motif.

Untitled, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 200 × 160 cm

Untitled, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 200 × 160 cm

Untitled, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 200 × 160 cm

Untitled, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 160 cm

Untitled, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 200 × 160 cm

Untitled, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 190 × 160 cm

005

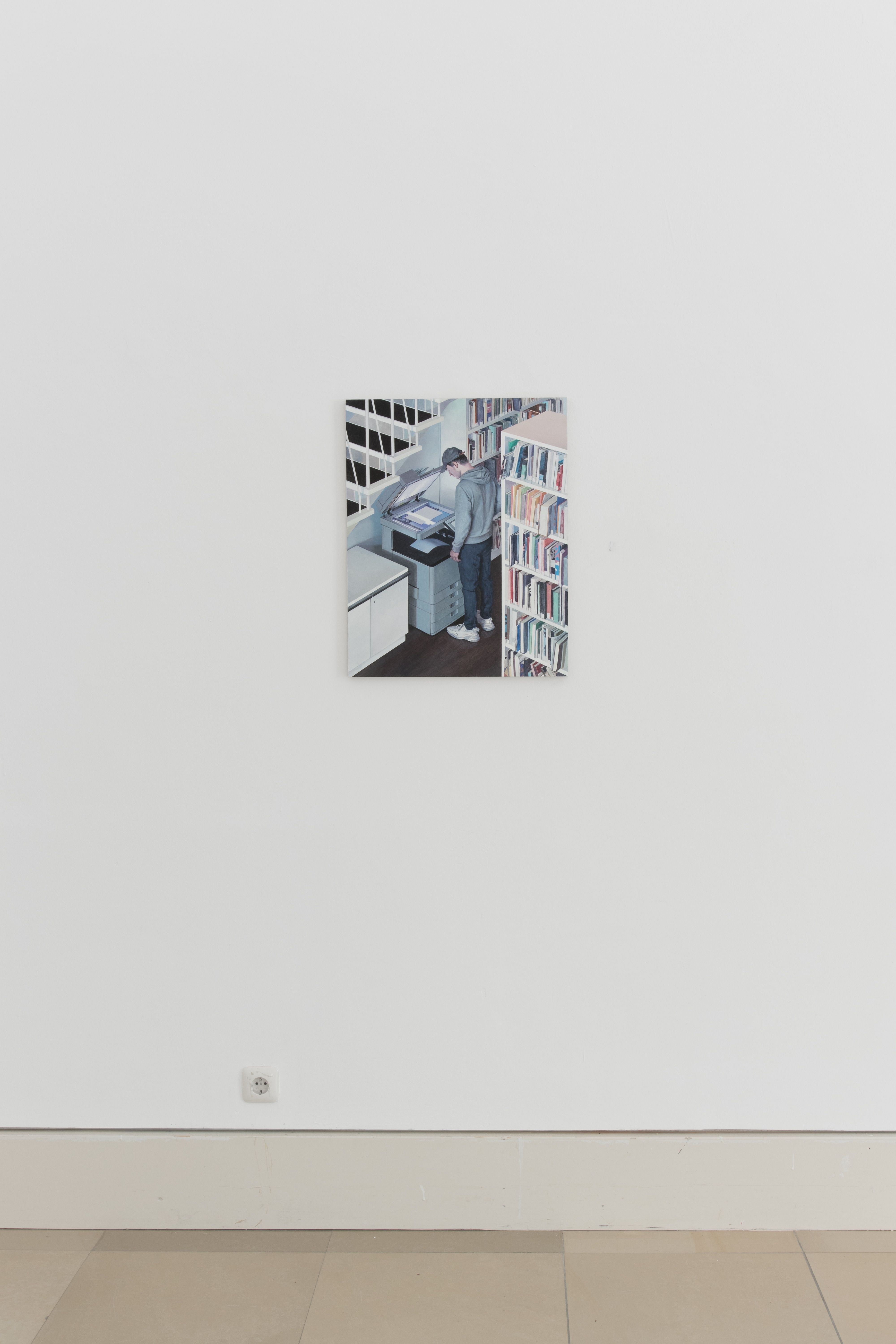

Copy Machine

Untitled, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 240 × 180 cm

Untitled, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 240 × 200 cm

004

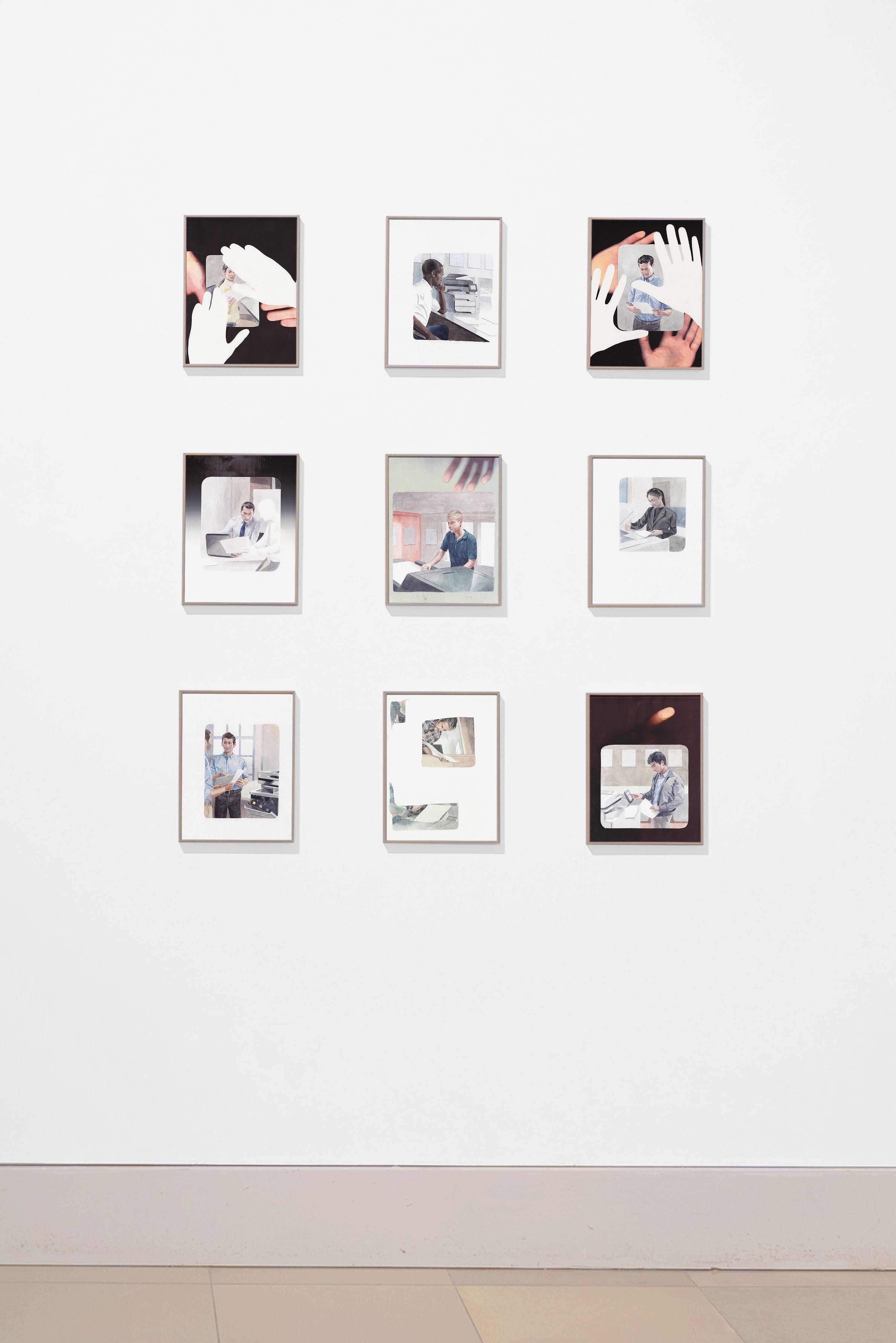

Key Operators

The series 'Key Operators' focuses on the examination of immaterial work and the material handling of paper, which serves as a carrier of information, ideas and modes of representation. The watercolours and prints are based on stock images, generic material from image databases produced and used for illustrative purposes in advertising and the press. They depict people, primarily men, in office situations. By handling paper, computers and printers, they suggest cognitive but repetitive work. The devices are part of the image as watercolour depictions of the concrete technical machines as well as the result of their use. The pictorial space is additionally expanded by to scale prints of hands and their silhouettes, implying work taking place in the background. Certain works consist of watercolour on paper, others have additional inkjet-printed sections.

All 18 works: Untitled, 2018/2019, watercolour and inkjet-print on paper, 32 × 24 cm

Book

How To

'How To' combines various found assembly instructions and my own drawings to create a unique publication. It focuses on the stripped-down beauty of functional drawings and their ability to establish a direct connection with the viewer. The informational aesthetics are progressively called into question by their repetition, distortion and exaggerated juxtapositions. The drawings in the publication have an instructional quality, yet they remain a call to action without a clear referent. The laserprinted booklet is presented in a sober brochure box attached to the wall and is free to take away for exhibition visitors. It measures 15 × 21 cm.

003

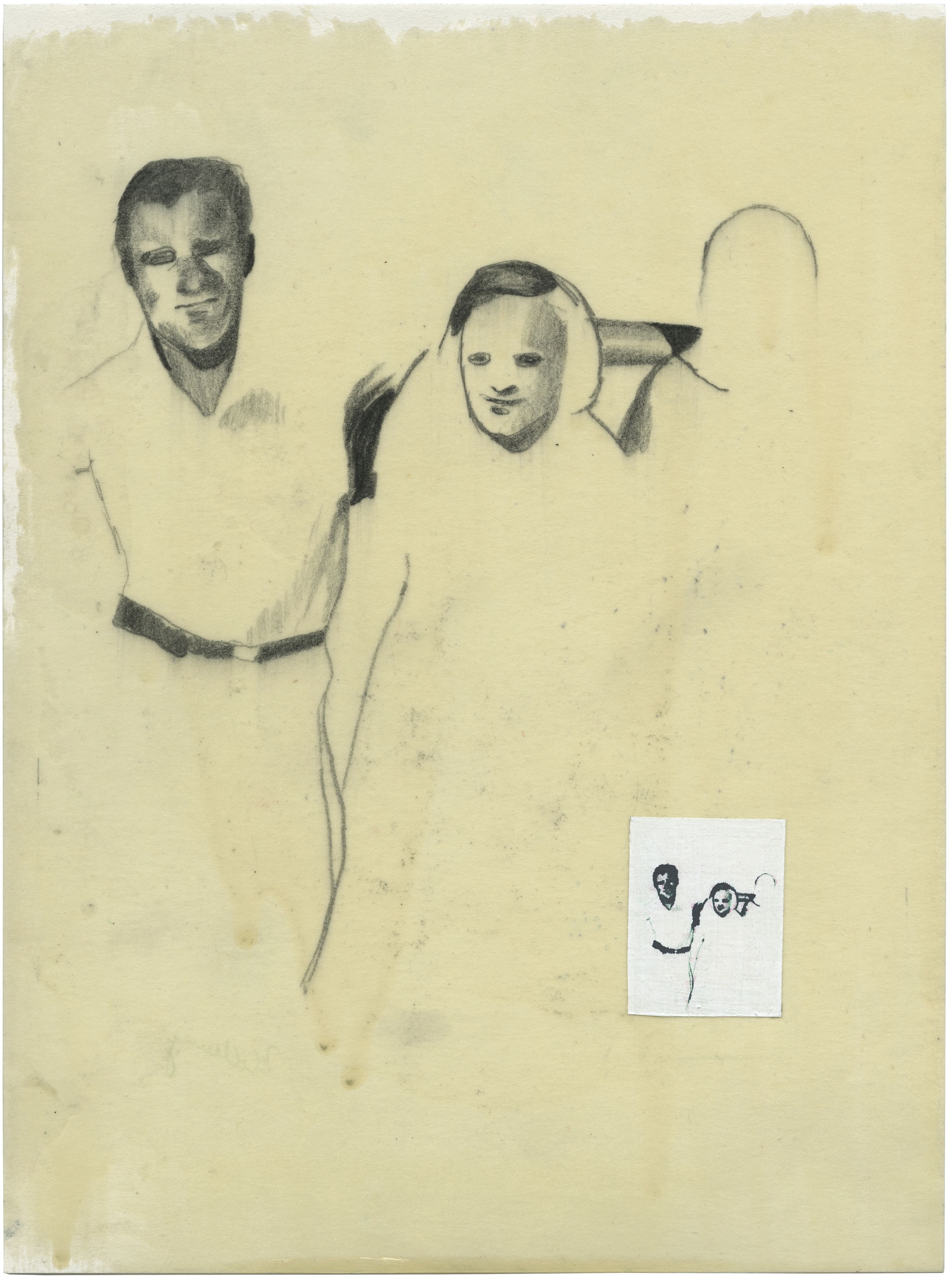

Alternatives

The series 'Alternatives' depicts a person with rake in four similar paintings. All four motifs relate to four nearly identical photographs previously created for this purpose. The painterly translation of the motifs results in an added layer of difference between the images.

All 4 works: Untitled, 2019, acrylic on MDF, 40 × 30 cm

002

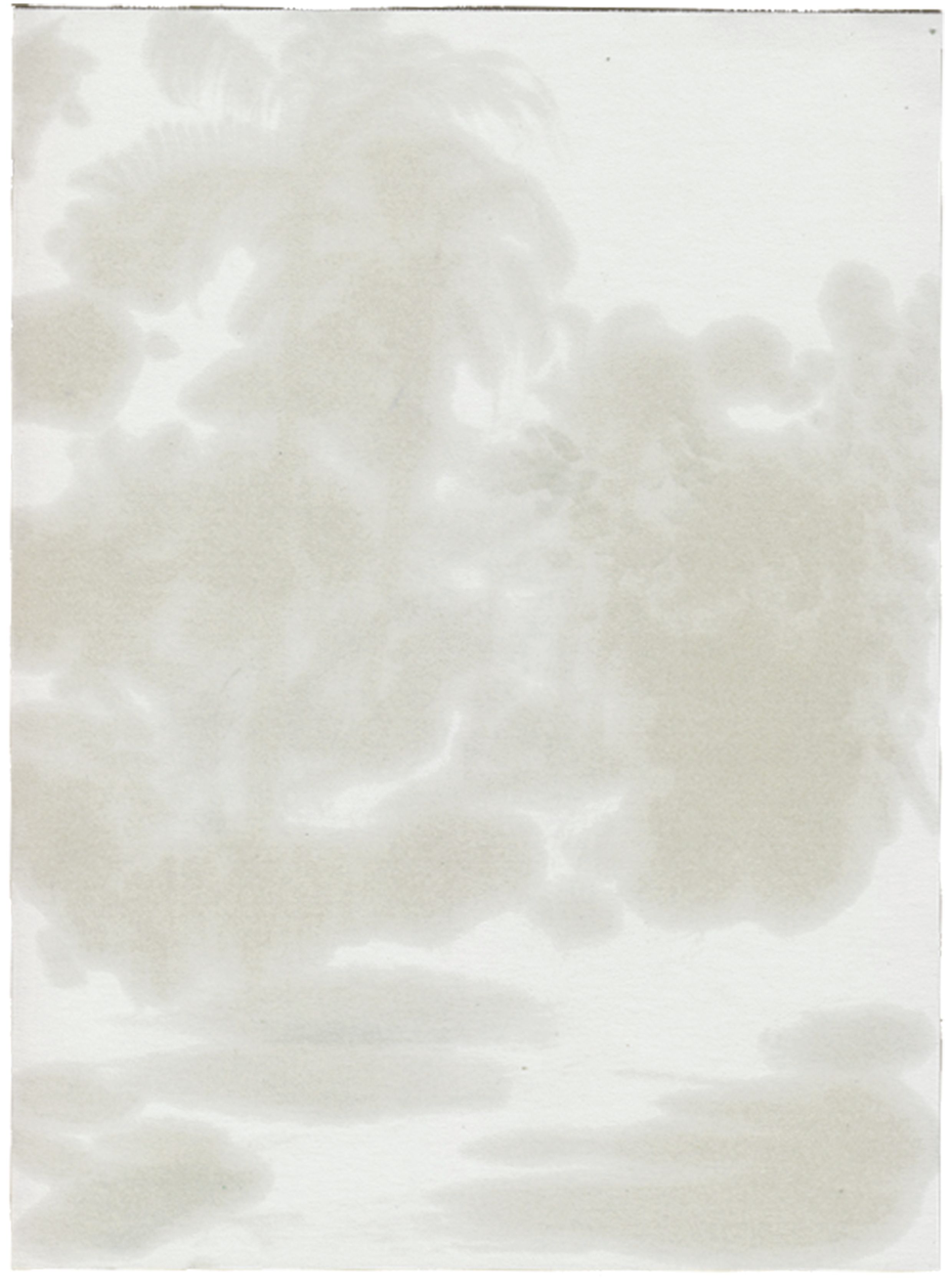

Backgrounds

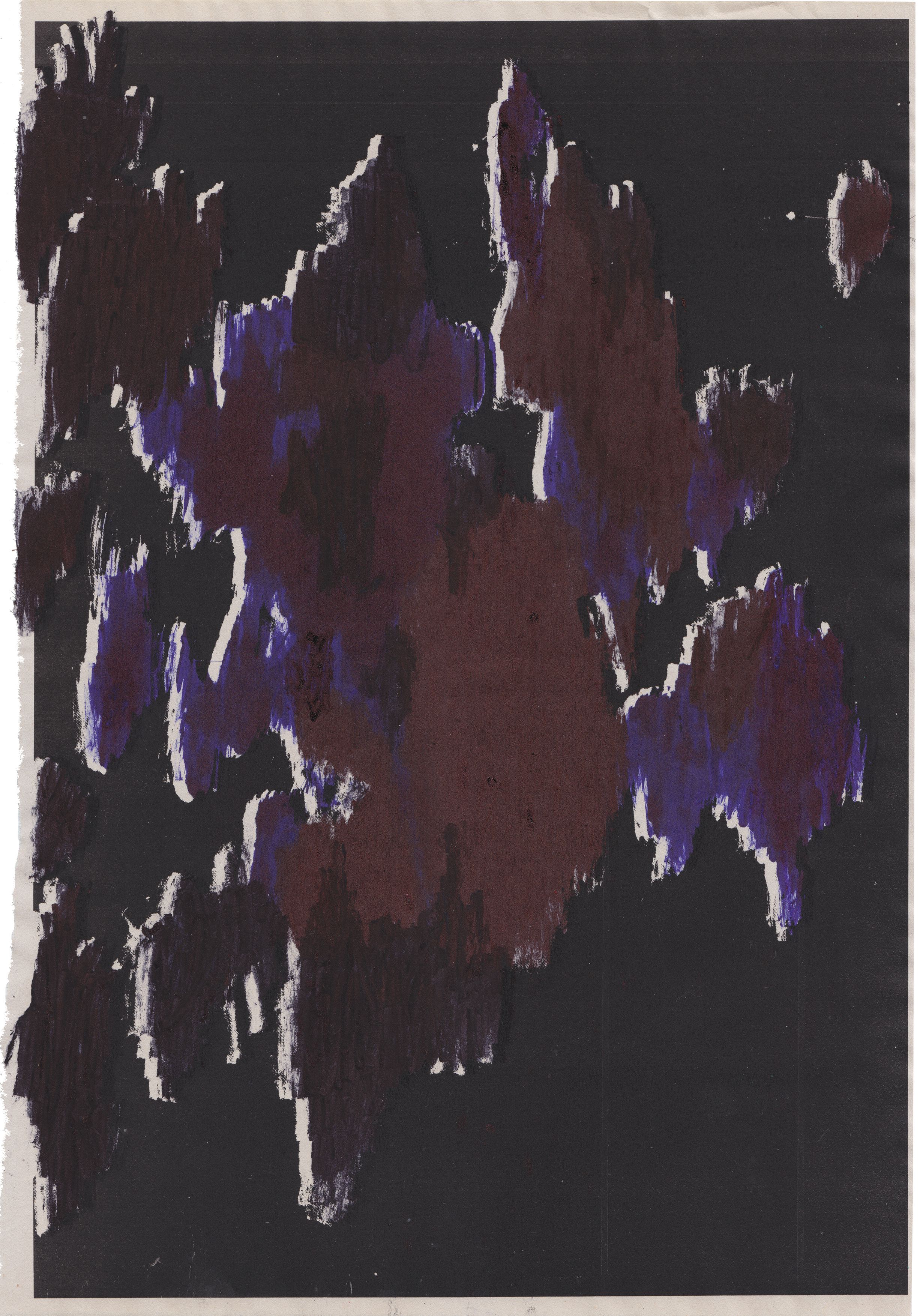

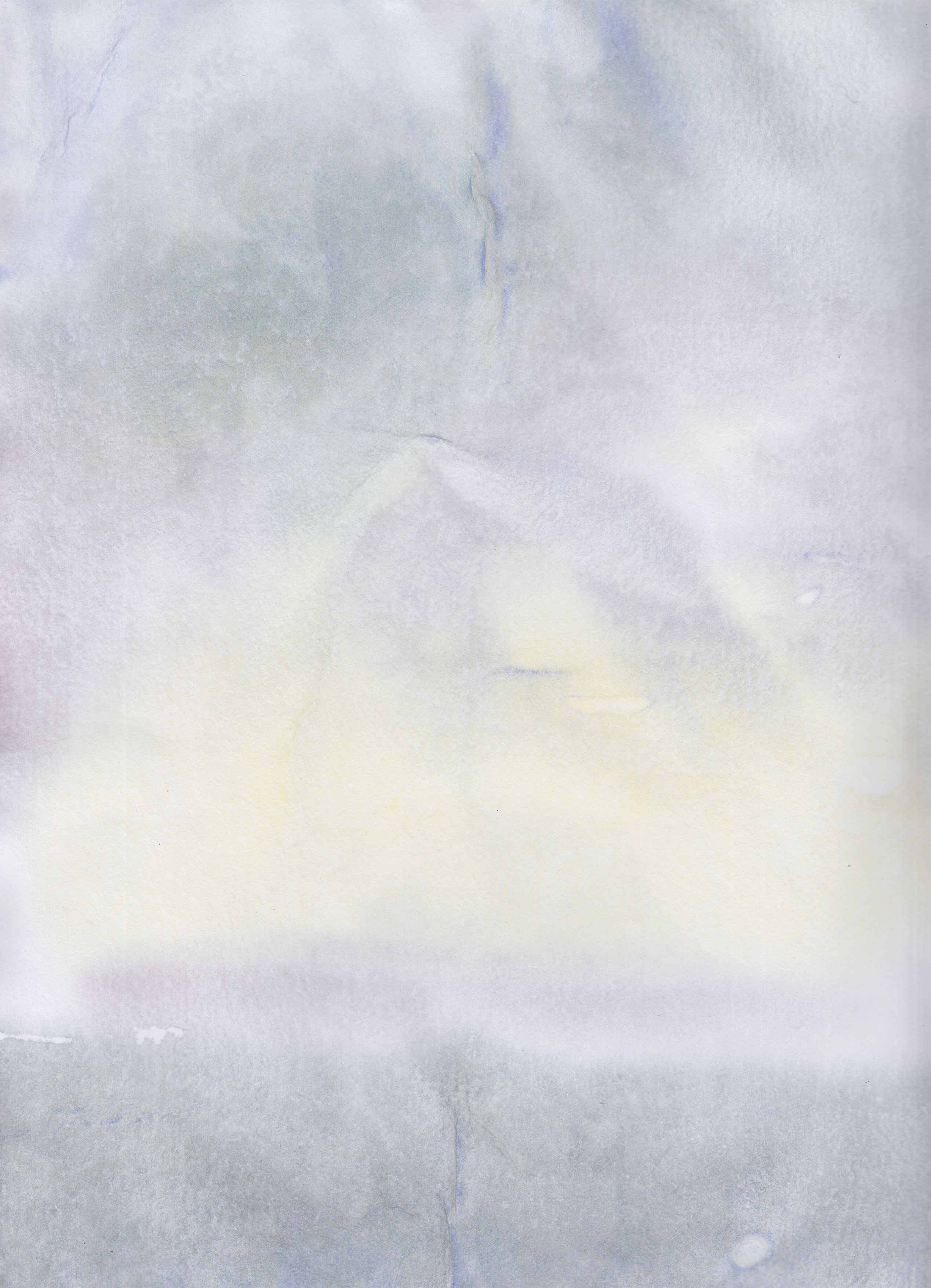

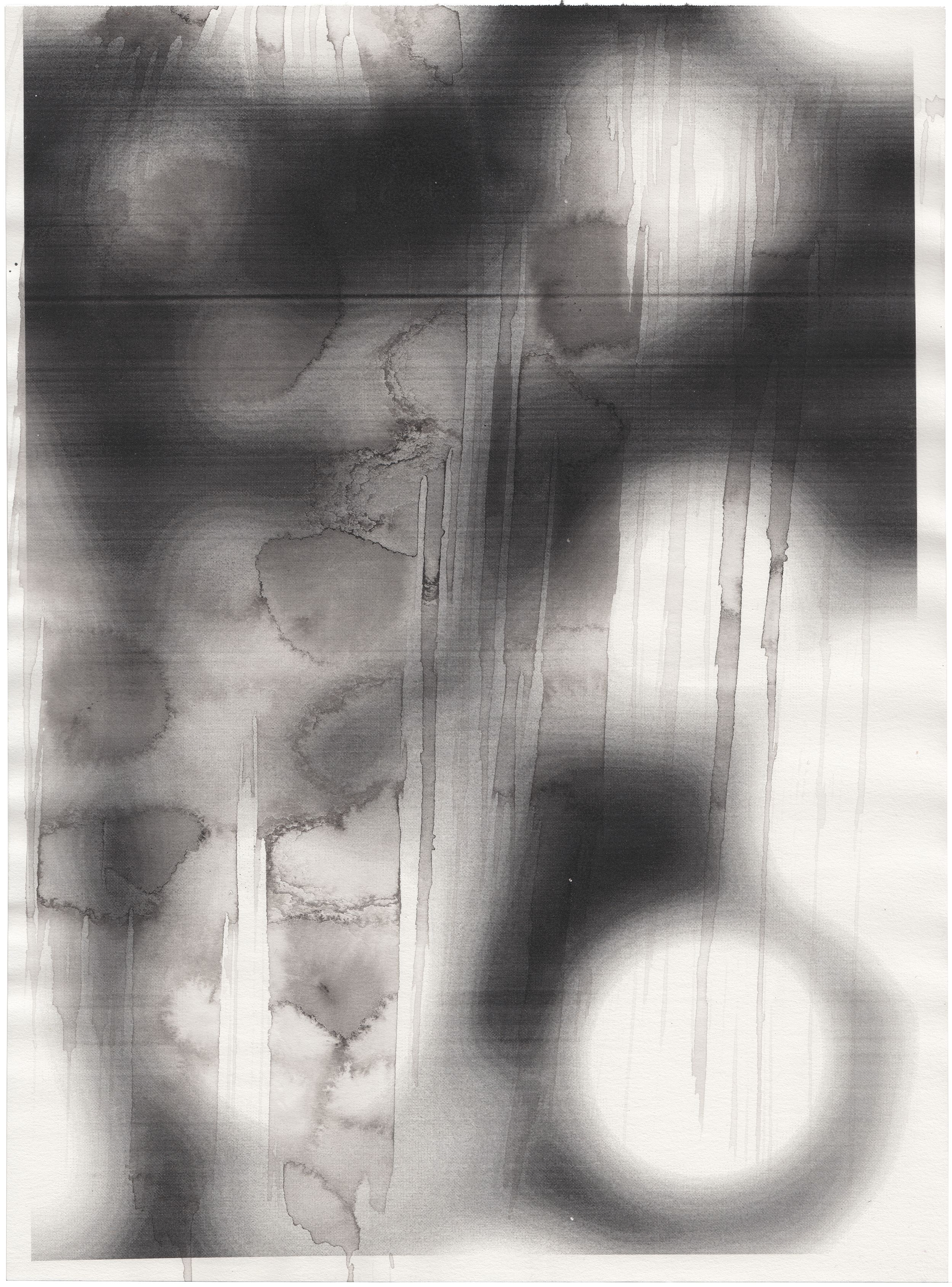

The work 'Backgrounds' consists of 27 manual reproductions based on a found advertising photograph. The advertised object is omitted in favour of the background. Over 27 days, 27 variations of the same motif were created in the studio through the repeated attempt to establish a relationship of similarity between the photographic template and the painted image. The imprecision of the painterly process results in a multitude of images that are similar but never exactly alike.

All 27 works: Untitled, 2017/2018, watercolor on paper, 42 × 29.7 cm

001

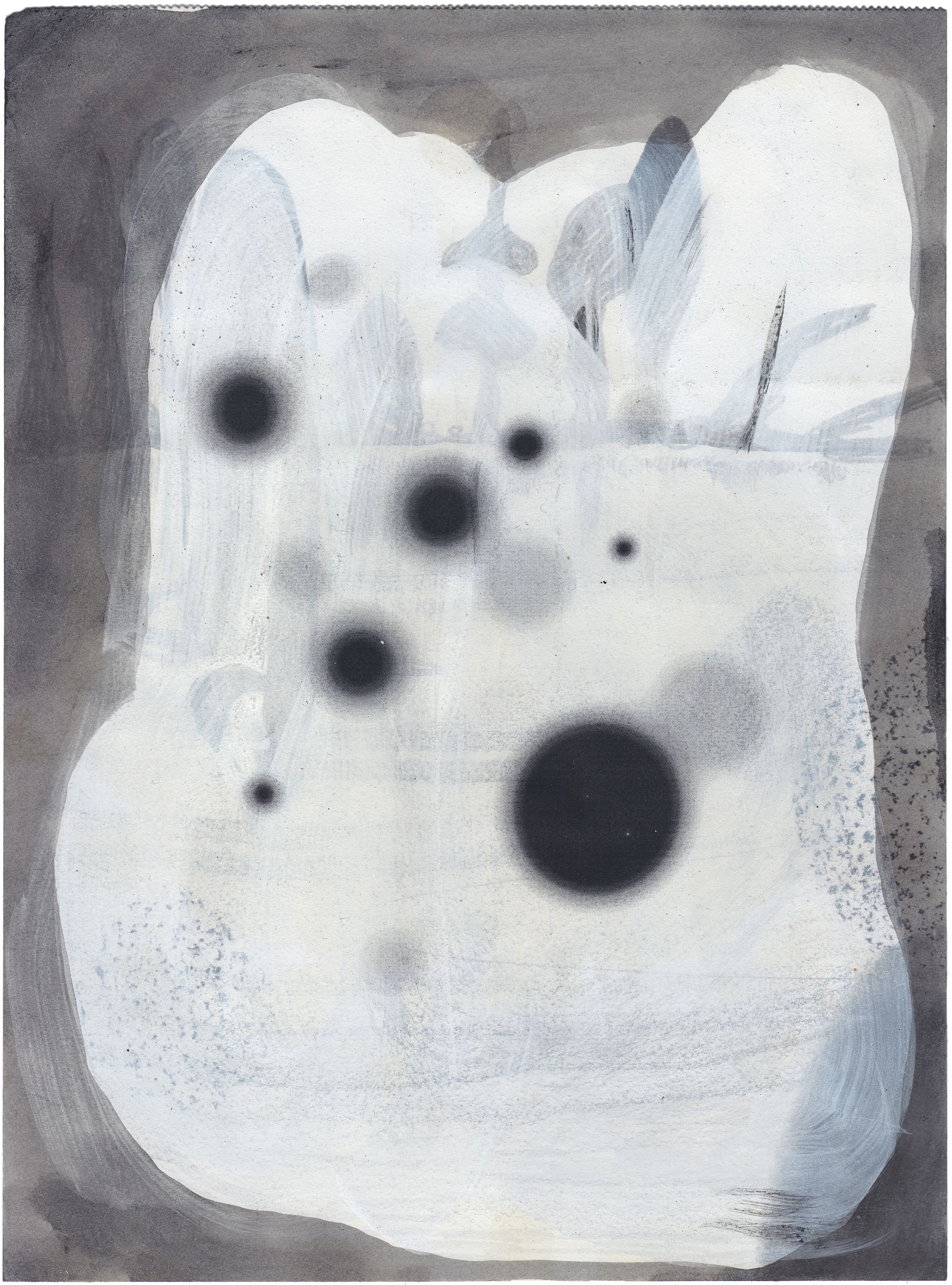

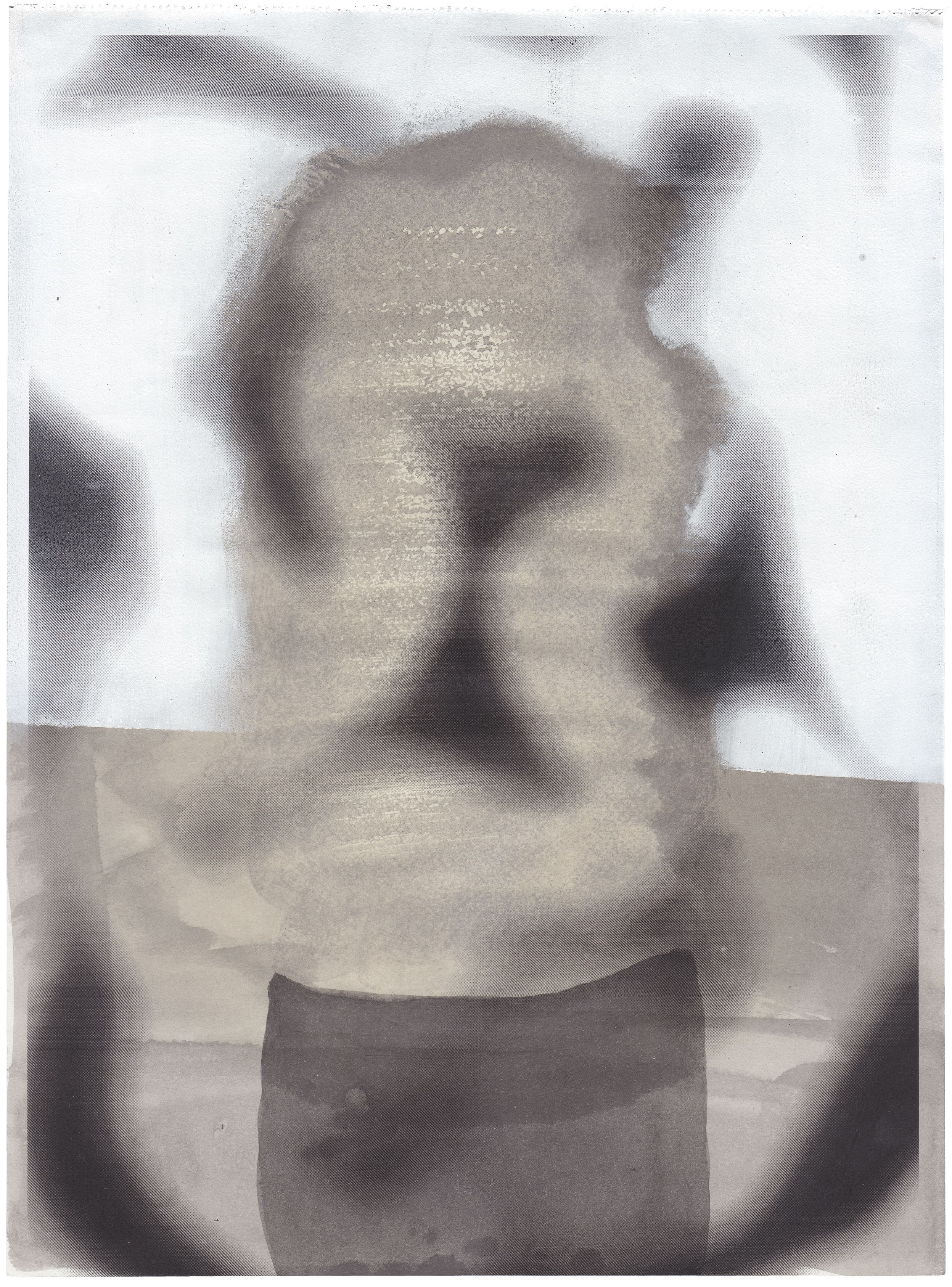

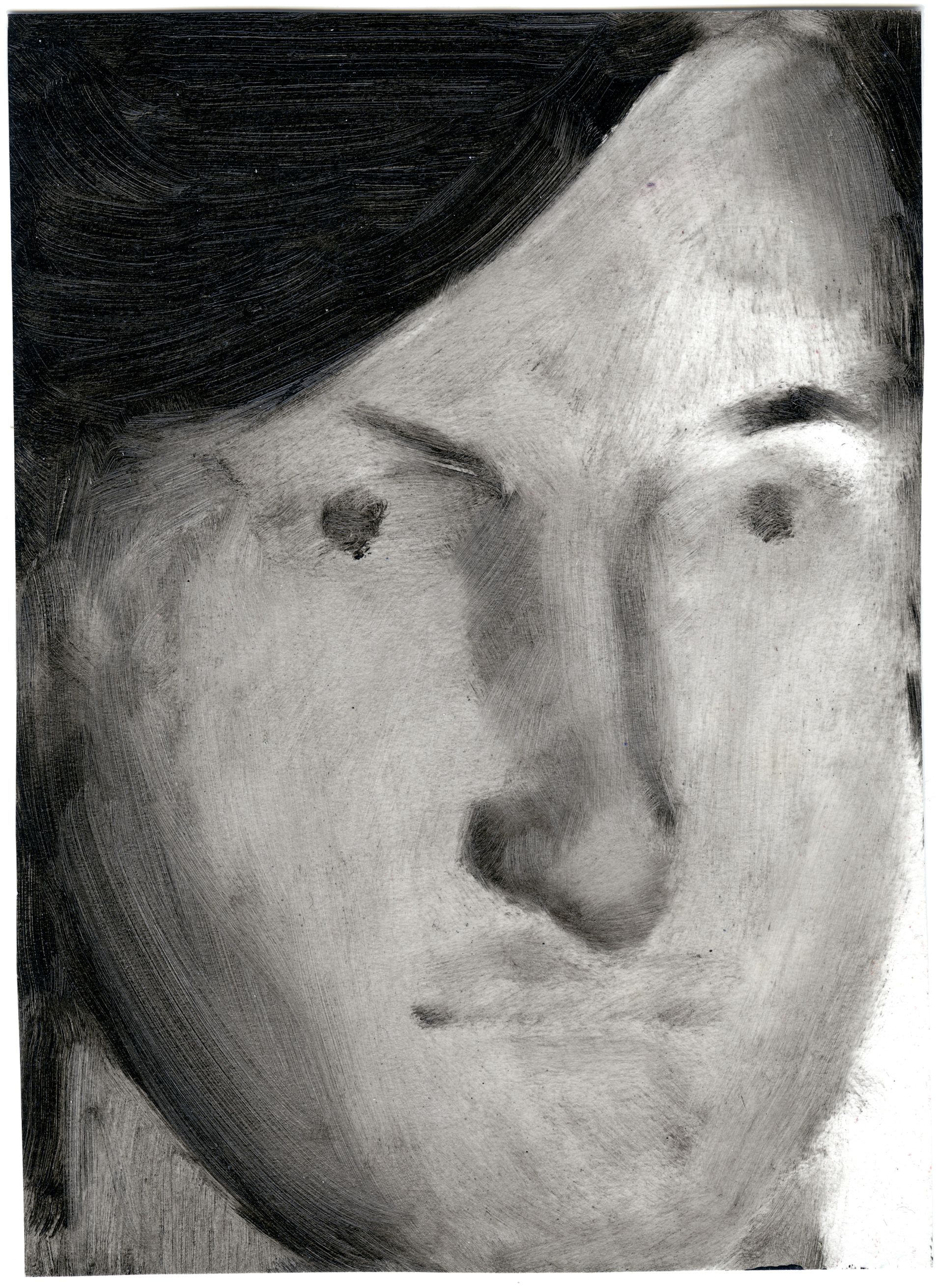

Set #1

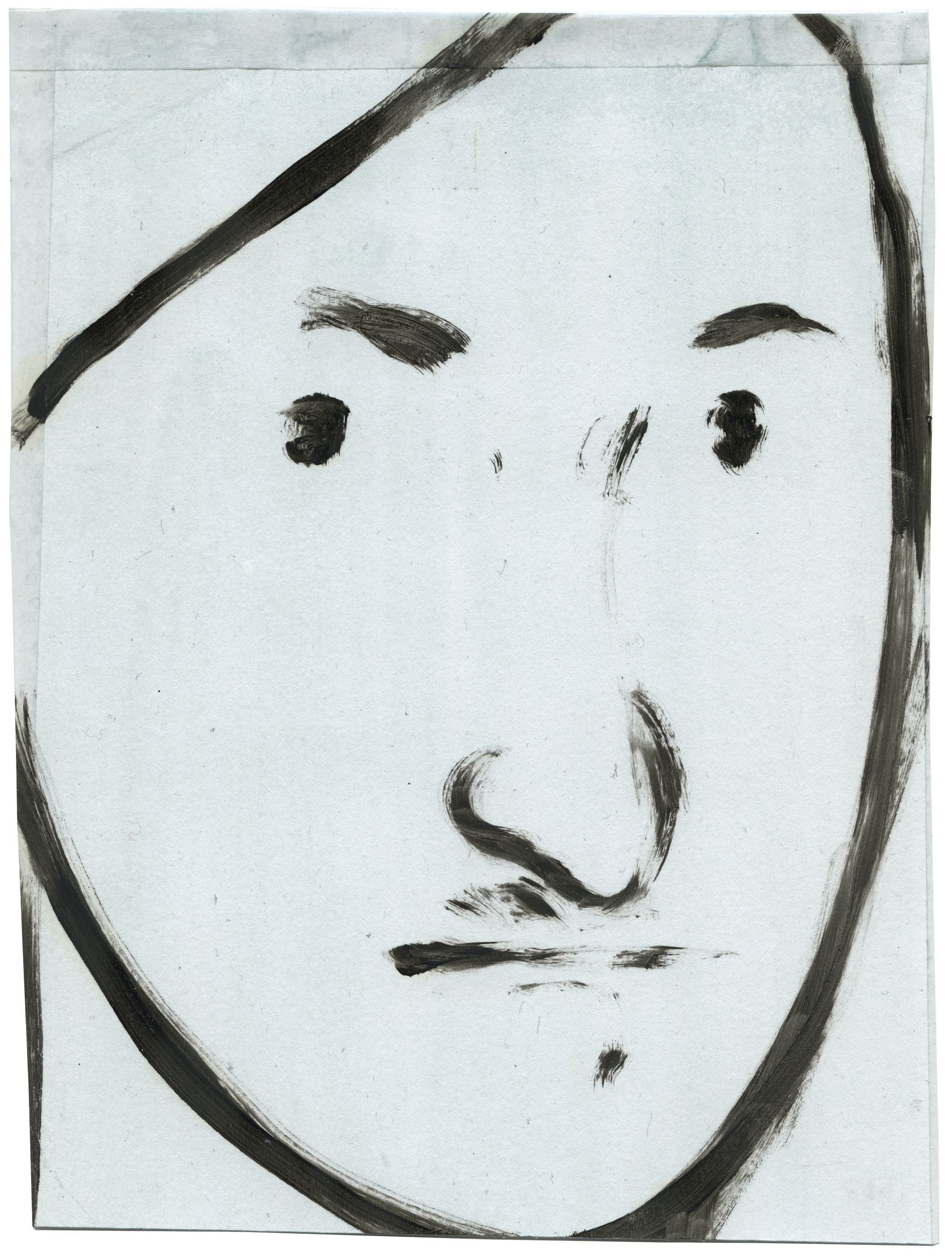

Sixteen works on paper that are presented as a set. In addition to landscapes, plant still lifes and figures, the images show motifs that are only remotely reminiscent of a specific object. In some cases the watercolors and ink drawings are overprinted with an inkjet printer, so that original and reproduction can no longer be separated.

Untitled, 2017, ink and laser print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, watercolour on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, ink, acrylic and laser print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, ink and laser print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, oil on paper, 26 × 18 cm

Untitled, 2017, ink and laser print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, watercolour and inkjet print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, watercolour on paper, 26 × 18 cm

Untitled, 2017, watercolour and inkjet print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, ink, acrylic and laser print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, watercolour and inkjet print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, watercolour and inkjet print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, oil on paper, 26 × 18 cm

Untitled, 2017, watercolour and inkjet print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, linseed oil on paper, 29 × 21 cm

Untitled, 2017, graphite, resin, acrylic and inkjet print on paper, 29 × 21 cm

013

Neue Stille

Kunstmuseum Heidenheim, Heidenheim, 09.11.2024 – 16.02.2025

In view of the challenges of the present, there are numerous indications of a renewed longing for outdoor recreation. Taking this as an opportunity, the exhibition in the Hugo Rupf Saal asks whether the current enthusiasm for the outdoors is a phenomenon for society as a whole that is also echoed in art. Can we speak of a comeback of Romanticism 250 years after Caspar David Friedrich's birth?

In the exhibition, photographs, paintings, thread paintings and video works by nine artists invite the public to explore artistically interpreted landscapes in order to reflect on our emotional reaction to nature, its representations and perceptions.

The exhibition follows two narratives. To this end, an intimate cabinet room will be created in the former swimming pool hall. Inside, the mostly deserted, sometimes melancholy depictions invite quiet contemplation and ask whether it is still possible in today's fast-paced world to linger in front of a picture for a long time and find peace. In contrast, there are works on the outside walls of the cabinet that critically question or deliberately irritate our relationship to nature and the motifs of Romanticism. The exhibition booklet reflects these different approaches to the subject matter and approaches the works on display on both an art historical and a personal level (download as PDF).

Artists: Thomas Bergner, Jonah Gebka, Jan Gemeinhardt, Robert F. Hammerstiel, Karen Irmer, Linda Männel, Jonas Maria Ried & Florian Post, Clemens Tremmel

012

Why Look At Humans?

Studio, Munich, 21.06.2024 – 23.06.2024

In his essay 'Why Look At Animals?' (1980), author John Berger examines how the age-old relationship between humans and nature has broken down in the modern consumer age. Animals, which used to be at the center of our existence, are now marginalized and reduced to a spectacle. At one point Berger writes: "...animals are always the observed. The fact that they can observe us has lost all meaning." In a first attempt to take this fact into account, the exhibition project 'Why Look At Humans?' explores moments in which the relationship between species can be reconsidered and viewing hierarchies reversed: Why look at humans at all?

Artists: Gisela Carbajal Rodríguez, Jonah Gebka, Claudia Holzinger, Felix Klee and Raphael Unger.

011

Hosti·pets

Tiffany Street, Providence, 23.03.2024 – 20.04.2024

Hosti·pets is a show gesturing towards an impossible ethics, mapping the aporetic moment, where the dream of universal hospitality founders on its own threshold. It is curated by poet and writer Ulrich Baer and combines his text 'Video Nasty' with a video by art collective Alterotics, a song by musician Big Step, tufted sculptures by Eseosa Ekiawowo Edebiri and four watercolours from my series 'Moody Layouts'.

010

Double Double, Magdalena Wisniowska

…There are two very different types of relations: intrinsic relations of couples involving well-determined aggregates or elements (social classes, men and women, this or that particular person), and less localizable relations that are always external to themselves and instead concern flows and particles eluding those classes, sexes, and persons. Why are the latter relations of doubles rather than of couples? (1)

There are always two present in Jonah Gebka’s work, never the one. It can be the image and its copy, whether this is a photocopy, a book or a screen, as was the case in his earlier series of paintings. It can also be a frame within a frame, going from canvas edge, to computer screen to desktop icon. Elsewhere: the grid of the bedspread versus the grid of the open laptop. A laptop too consists of two parts, light and dark.

In his latest series of small watercolour paintings on paper, there are two figures sitting face to face. We as the viewer sit behind them, so that the back of the head of the first figure obscures the face of the second further away. Often there is a barrier between the two, like a laptop or an iPad. Sometimes the knees or elbows get in between, raised up and hugging the body. And we know immediately who this couple is. They spend evenings at home in the semi-dark, watching Netflix on the sofa while distractedly scrolling through their feeds, occasionally sending each other that Instagram reel of a cat singing. Insta-besties = end of relationship #date #datingadvice. Their roles, their place in life, are well-defined and clear.

But what do Deleuze and Guattari mean when they say that there exist relations external to themselves? Less localisable concerning flows? What is the double that makes it so different to the couple? Well, the couple is familiar. We know who the protagonists are and what their relationship is like. Who they are defines the relationship they have. But when the relation is external, the protagonists are no longer defined by any connection they have with each other or indeed the connections they make with anyone or anything else. Instead, there is only person one and person two, and their current bond. “And” and “and” - and as Deleuze argues, in this world “and” is the conjunction that dethrones the interiority of the verb “is.” When looking at Jonah’s paintings it is striking that Deleuze calls this world of the double “a harlequin world of colour patterns,” especially as his is not a discussion of art, but of Hume’s empiricism. For this is what the world in Jonah’s paintings looks like: covered in the tartan blankets’ checkered grid.

There are always two present in Jonah Gebka’s work. Person one and person two. We do not know them - we only see the back of a head or a glimpse of a profile in darkness. In between and separating them are layers of plaid cloth, lines woven top to bottom and left to right, occasionally on a diagonal. The cloth’s pattern is both what flattens the pictorial space and produces the image. Person one and person two and an abstract world of line and colour binding the two. Each element separate and distinct and together.

(1) Gilles Deleuze und Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, Engl. Übers. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 196.

Magdalena Wisniowska, 2024

009

Moody Layouts

Strobe, New York, 20.10.2023 – 22.10.2023

The thirteen watercolors shown in 'Moody Layouts' are part of a body of work that positions various figures and objects inside a grid of plaid patterns. The paintings were hung at regular intervals throughout the space and accompanied by a short rhyme in the press release (download as PDF).

008

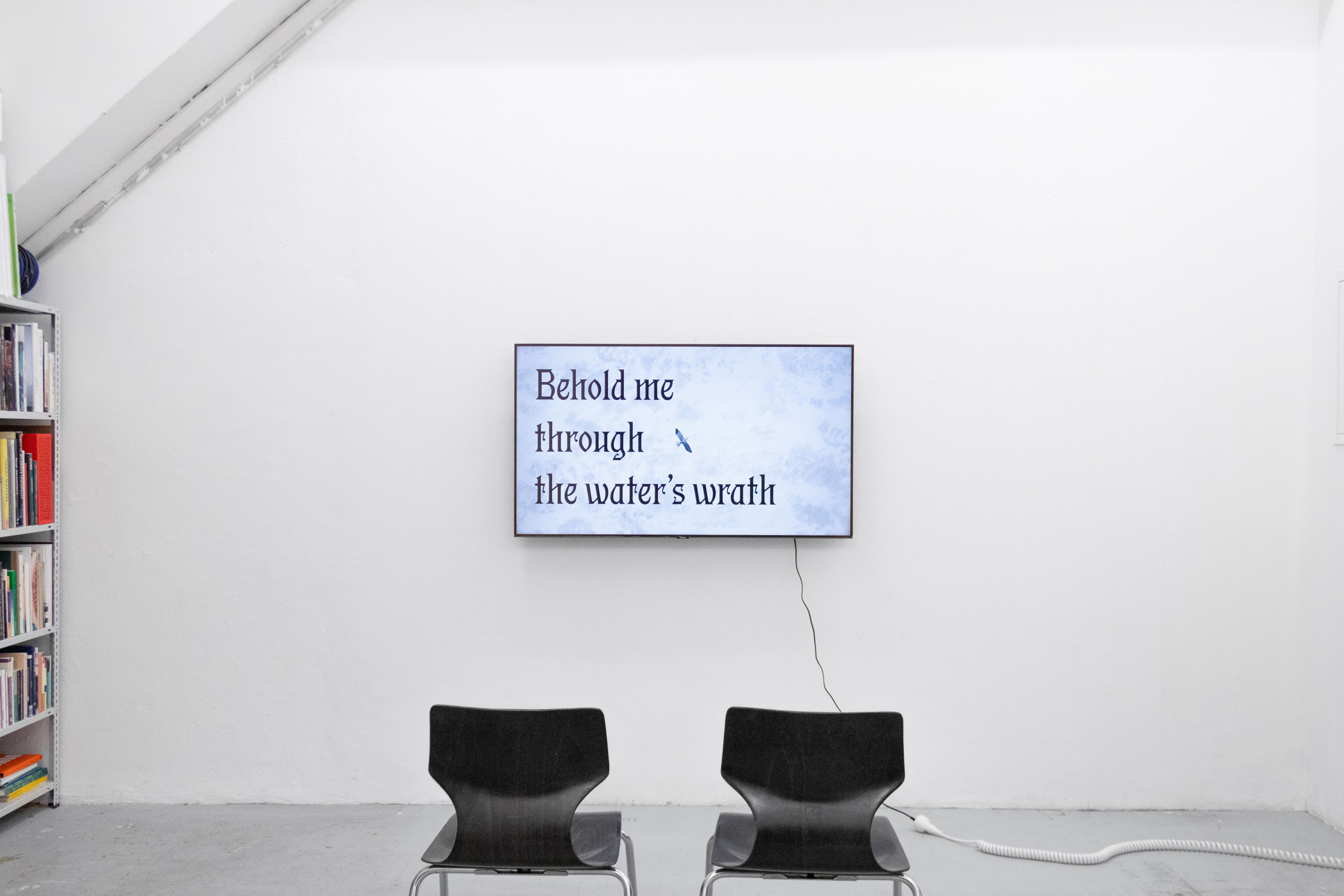

Blue Light

Boutwell Schabrowsky, Munich, 20.10.2022 – 26.11.2022

'Blue Light' consisted of six paintings installed in the gallery space as well as the text 'California Dreamin'…' by art historian Jana Kreutzer, that deals with the landscape motifs seen in the paintings on view. The accompanying artist book 'Browser' unites limerick-like rhymes and text fragments with drawings from sketchbooks used in the period leading up to the exhibition. A new collaborative videowork with filmmaker Max Draper employs the so called Desktop Documentary genre as a starting point to explore themes of communication, translation, and misunderstanding. It was presented online following the exhibition's run.

Text

California Dreamin’…, Jana Kreutzer

In his exhibition Blue Light, Jonah Gebka incorporates into his paintings reproductions of iconic contemporary landscapes: the preinstalled wallpapers of Apple’s macOS operating system. Since 2013, the US company has been naming new upgrades of its operating system after Californian locations and using their photographs as wallpaper. As a result, seven photographs of Californian natural landmarks have found their way onto the desktops of almost a hundred million macOS users worldwide.

Gebka makes use of their recognition value and the familiarity this creates: the photographs, without authorship, have inevitably anchored themselves like iconic representations of bygone eras, into the current viewing habits of many in this age of digital work and life. The most striking example of this casual iconization is Charles O’Rear’s photograph Bliss. Microsoft used it as the desktop background for its Windows XP operating system from 2000. The green hill under a bright blue Californian sky is now considered the most viewed photograph in the world.

By referencing Apple’s landscapes through painting, Gebka anchors Blue Light firmly in the digital imagery of the present, but by embedding these landscapes in everyday, almost banal scenes, he undermines their pathos. Gebka captures specific moments in the series: seemingly insurmountable sleeplessness, endless binge-watching just before eyes get heavy and fall shut, or unfulfilled tasks that raise their heads in the middle of the night. The nocturnal scenes are reminiscent of a very specific form of restlessness that is able to keep a tired mind awake despite physical exhaustion.

Blue Light refers to the light from screens and displays, which can contribute precisely to this insomnia and its accompanying malaise. A stimulus expansion of cells leads the human brain to believe that it is daytime. Special screen glasses, creams with blue light filters and “night screens” try to ward off this danger, this blue screen hazard. Yet not even these countermeasures can impede the melancholy of Gebka’s series of images, for the constructed scenes evoke a haunting, mournful feeling. By means of painterly layers of sharpness and blur, Gebka creates intimate, private scenes. In their constructed quality they are reminiscent of film or fiction, and at the same time, in their immediacy and randomness, they are very close to many people’s reality.

Gebka paints zoomed-in sections on large-format canvases. The nocturnal scenes are magnified as if through a lens, counteracting the theatrical expanse of the Apple landscapes. We don’t know what else is happening in the space Gebka depicts, because the edge of the screen also limits the story being told. What takes place in front of the screen—anonymous backs of heads and profiles of faces, bent elbows in plaid shirts, and pointing hands—seems flat, almost like paper cuttings. The landscapes are painterly, reminiscent of soft watercolors. In contrast, the icons depicted on the screen are almost realistic. These clickable symbols are the crisp moment; they are the gateway to the vastness of the strangely familiar-looking landscape. Around the same time as Blue Light opens, the new macOS upgrade Ventura will be launched, presumably with an abstract graphic as the background of the default setting. Only the name of the upgrade remains a reminiscence of the Californian landscape.

…on such a winter’s day.

Jana Kreutzer, 2022

Download as PDF

007

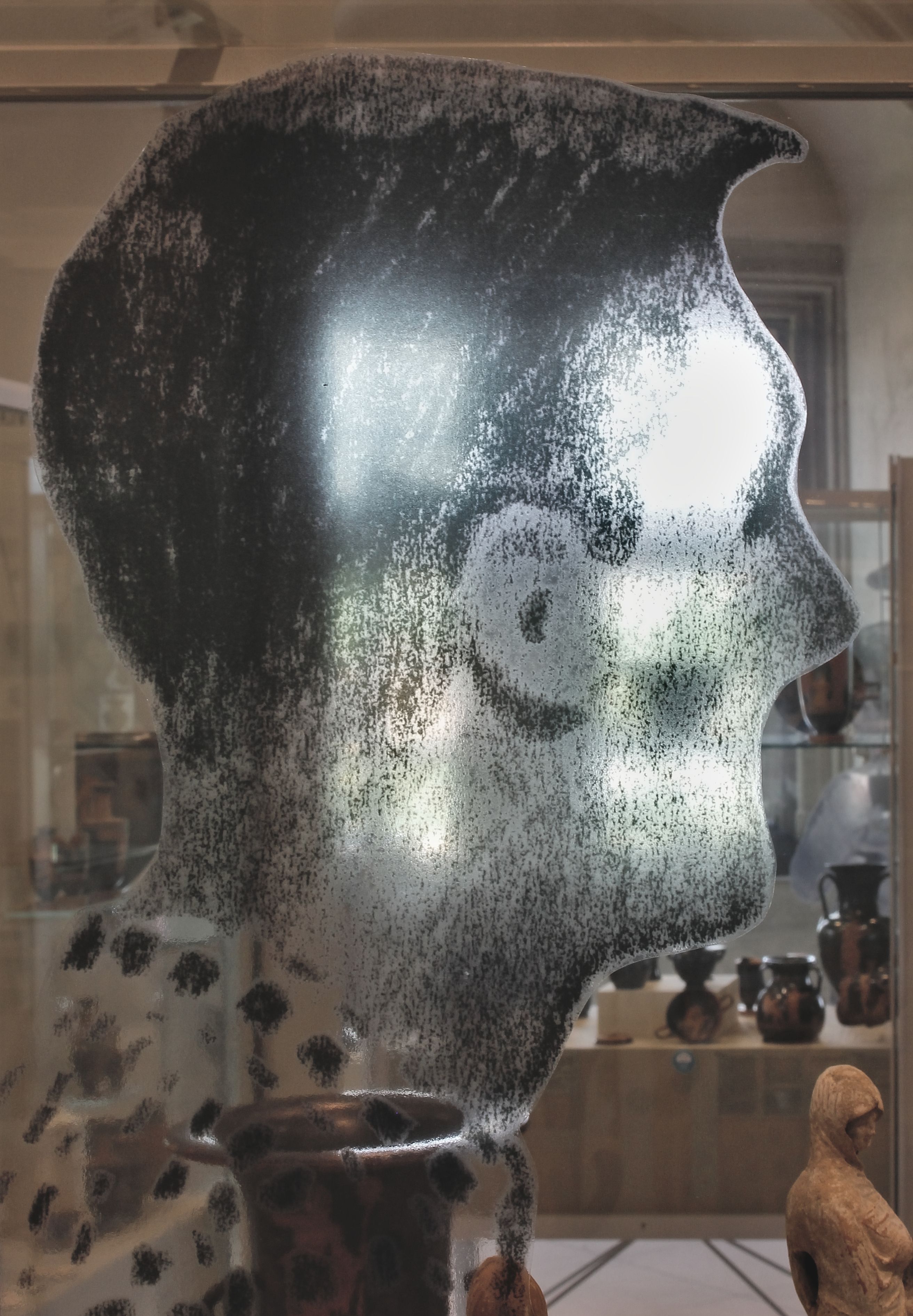

Looking Glass

Museum of the University Tübingen / Ancient Cultures, Tübingen, 06.05.2022 – 16.05.2022

The presentation 'Looking Glass' consisted of drawings attached as partially transparent prints on foil to the display cases of the Museum Ancient Cultures in Tübingen. The drawings and their positioning picked up on both spatial and content-related aspects of the collection: Figures immersed in contemplation are juxtaposed with fragmentary representations of selected objects from the collection. The connecting element is formed by the gazes of the figurative representations. A limited edition booklet was available for free as part of the exhibition. It contains drawings and a text by art historian David Kühner.

006

re:working archives

PLATFORM, Munich, 02.02.2022 – 18.02.2022

The group show 're:working archives' brought together work by artists Dominik Bais, Cana Bilir-Meier, Philipp Gufler, Hyesun Jung and myself, which alter, revise or redefine common notions of the archive. The artworks were shown alongside representative loans from independent (non-governmental) archives AAP Archive Artist Publications and Forum Queeres Archiv München e.V.. By doing so, curator Julia Wittmann presented history and its archiving as an unfinished construct. Exhibition views by Manuel Nieberle.

005

Take Your Time

Boutwell Schabrowsky, Munich, 06.05.2021 – 12.06.2021

The solo exhibition 'Take your time' presented 40 works from the series 'A—Z', lined up in regular intervals on the walls of the gallery. Two texts and a film accompanied the exhibition. The essays 'The Space of Translation' by Peter Westwood and 'Repeatedly Reaching For Questions Not Quite to Grasp' by Johanna Strobel deal with media translation processes and the relationship of reproduction and original. The film 'How To', made in collaboration with filmmaker Max Draper, restages various processes leading up to the exhibition and is narrated by a voiceover that provides detailed instructions on how to produce the paintings shown in the exhibition.

Text

Repeatedly Reaching For Answers Not Quite to Grasp, Johanna Strobel

Figuratively speaking I imagine Jonah’s paintings being on the high noon position of a circular line of image distribution; as if his works would surface from a referential stock archive to take a deep breath before becoming references for subsequent works or diving back as documentation jpegs into Hito Steyerl’s swarm circulation of the poor image where there is no tracing back to a primary original anymore (Steyerl, 2009). While Jonah’s handcrafted paintings are inherently as authentic and unique as can be, their motifs come from a long lineage of simultaneous reproductions of similar versions and reaffirmations that don’t allow a tracing back of what references what.

The aesthetics of stock photography his motifs incorporate (whether because they actually are, or mimic stock images) produces a sense of apparent neutrality through ubiquity and conformity, when of course this imagery actually reproduces corporate monoculture. But Jonah doesn’t use these images as subject matter. He borrows their aesthetics and pictorial content which he utilizes and transforms into patterns and reappearing themes. The recurring and repeated motifs serve conceptual purposes beyond of what is represented and produce meaning in an extended context. They open up a mental space inviting the viewer not to act but to pause and hand themselves over to contemplate the given moment stretched by a frozen action.

The body of work presented at the gallery depicts hands pulling books from, or putting them back onto shelves. The gestures of the respective painted hands are ambiguous. Though they are repetitive, the gestures are not identical. Each painting is unique in composition, size and color while the motif, a book pulled out / put back on a shelf by one or a pair of hands, stays the same. The covers of the books on the shelves are blank and mainly monochrome. They neither show text nor images. The books’ contents are emptied out. They become props for the hands; only the gesture of taking the books out of, or putting them back onto the shelf remains. But without the books’ content this gesture loses its meaning as well. Books without titles and covers cannot be indexed and put into order. Empty books contain no knowledge or information. There is no point in pulling an empty book from a shelf; nothing can be looked up. Maybe the hands are frozen or paused in the moment of realization, that there is no information to be retrieved and so in the second after that realization, the book will be pushed back in line again to the empty others on the shelf.

The shared motif of the paintings is repeated over and over again but still the paintings are not reproducing or copying each other. All the works are painted after composed referential photos, so in that sense they are reproductions of preceding images and thus can be simultaneously seen as copies and unique originals. Within their variety they are not redundant but they seem to be retaken versions of one another without hierarchy and referential order. The paintings follow each other in their serial progression and thus avoid the inferences of relational composition. This undermining of referential ordering through repetition subverts representation, while the specificity of the repeated motif, the individual gestures, produces tension between these works as non-identical but still copied originals.

Today, as most books are probably written and designed using computers, the manuscript of a book is only a digital file, which for now leaves the question of the unique original of a book unanswered (probably at least until that file is minted as an nft and sold by amazon). Books as such, if they are part of the same edition, can be described as multiple identical copied originals while Jonah’s paintings could in the above sense be seen as unique non-identical original copies.

Johanna Strobel, 2021

Bibliography:

Steyerl, H. (2009). In Defense of the Poor Image. In E-flux, Issue #10. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/, accessed on 2021-04-13.

Download as PDF

Text

The Space of Translation, Peter Westwood

The act of making a translation might be thought of as seeking the real or endeavoring to find veracity. However, given its interpretive nature, a translation, and its original text can also be thought of as slightly uneven parallel acquaintances, cohabiting a space made discernable for its atmosphere of variation and difference. Positing translation as essentially embedded within every act of speech, Mexican poet Octavio Paz, asserts that primacy and stability within a text are always in doubt. Paz questions the hierarchical relationships between original and translation, claiming that ‘...all texts are original because every text is distinctive.’ (Barnstone 1992, p. 5).

The idea that translation is a shifting space, prompts me to reflect on the way that all things within the world move through cycles of translation and reinterpretation. This is how our current times manifest – wherein versions and remakings seem to frequently inhabit most of what we encounter. Our period could be considered as forming through changing viewpoints, and interpretations, propelled through partial truths and fictions, circulated through social media, conventional media, and partisan politics (Rauch, 2020). Hence, in writing this during a pandemic, reflecting on how we might decipher what we see and hear, the phrase ‘uncertain, inconclusive shifting realities’ appositely emerges to typify the experience of our times.

Jonah Gebka’s exhibition, “Take Your Time”, presents us with the uncertainty of seeking a decisive or conclusive moment. His paintings appear to mediate on the idea of searching and locating within a regulated but ever-changing space. In fact, the images in each of his works appear as transitioning moments, instances where a person, decisively, or inconclusively, extends a hand to remove, or return, a text from a library. Libraries are regulated spaces, however, the disembodied actions of the hands that Gebka depicts seem unfixed, as if he is playing at the edge of order and disorder or evoking the randomness we experience in the passing of time.

Gebka represents hands enfolding books that are devoid of the signs and markings which might normally assist us in pinpointing their content. In fact, rather than being solely representations of books, the lack of any identifying features on each text – apart from the individual colour of book jackets – encourages us to consider the books as geometric shapes within a painting. In a roundabout way, this brings to mind Gerhard Richter’s frequent repudiations of the differences between abstraction and representation in painting (Elger & Obrist 1973, p. 72), and the inherent questioning this conjures in relation to the stability of representational painting. Sequenced as they are as a grouping of moments, Gebka’s paintings are equivocal, guiding us towards the undiluted visual sensation of colour and form as their eventual content. However, the imagery of Gebka’s paintings reflect on the conjectural nature of seeking, coupled with the physical act of looking – needless to say, a nucleus of painting.

Part of Gebka’s working method involves the process of photographically recording certain actions, which then filter through conscientious translations of the photograph into a painting. This is the space French philosopher Michel Foucault defined as the productive space between media (Soussloff, 2017), where a painting and a photograph, when intermingled in some way, enter into a state of between-ness: ‘... not a painting based on a photograph, nor a photograph made up to look like a painting, but an image caught in its trajectory from photograph to painting... (Hawker 2009, p. 272). Effectively, this is a translation from one source to another, where the solidity of each parallel acquaintance, photograph and painting, might be questioned. Gebka perceives his paintings as the translation of an image into a woven pattern where he is able to ponder the effect this translation may have on the original image – for Gebka, the recognition and sense of touch in painting becomes part of seeing (Weiland, 2020). Gebka’s paintings question the stability of representation as they evoke touch, intimacy and abstraction, where we in turn doubt that a book is simply a text, rather than a form, or a suggestion of moments in time. There is no doubt that we form narratives around the imagery in this work, and, in doing so, devise mutable associations. Although, his depictions of the selecting and returning of books seem to echo some of the uncertainty and repetitive nature of living, there is something recovering about eventually sidestepping these associations, to simply reside in the purely visual and abstract state of these paintings.

While we are mindful of the veracity of this visual abstract state, we hold a dual awareness within us between abstraction and the various associations we have in relation to the imagery. Each item being removed in the library, presumably taken into the world by someone, anyone, and then returned, makes us aware of the everyday. Beyond the banality of this act, we are reminded that our lives are composed and directed by temporal repetitions, iterative moments of being. This is ordinary time, where we return perpetually, repeating the moments in our lives that form and accumulate. Gebka’s works evoke the layered accumulations of things, of time, events, information and histories, remembering and forgetting – the veracity of living, which in the end might just be captured by the purity of a moment where we look, and are arrested by the sensation and experience of the purely visual.

Peter Westwood, 2021

Bibliography:

Barnstone, W. (1993). The poetics of translation: history, theory, practice. London: Yale University Press.

Elger, D., & Obrist, H. (Hrsg) (2007). Richter, interview with Irmeline Lebeer, 1973. Gerhard Richter – writings 1961 – 2007. London: Thames and Hudson.

Hawker, R. (2009). Idiom post-medium: Richter painting photography. In: Oxford Art Journal (Vol. 32, No. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rauch, J. (2020). What Trump has done to America: Three ways the outgoing president’s postelection fight changed the political landscape. In: Ideas, The Atlantic Magazine. Boston, Massachusetts.

Soussloff, C. (2017). Foucault on painting. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Weiland, M. (2020). Künstler, Künstlerin. Important artist conversation: Max Weiland talks with Jonah Gebka. In: Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eWZVCxFaxFY, accessed on 2021-10-02.

Download as PDF

004

Image Runner

Galerie der Künstler:innen, Munich, 08.09.2020 – 04.10.2020

The presentation 'Image Runner' was part of the series Debutant:innen by Berufsverband Bildender Künstlerinnen und Künstler München und Oberbayern e. V. In addition to my works, individual presentations by Helena Pho Duc and the artist duo Hennicker-Schmidt were on view in the gallery space. These were complemented by the artists' individual publications. 'Image Runner' was accompanied by the eponymous publication, published by Hammann von Mier Verlag. I additionally showed five large-scale works on canvas and nine works on paper from the series 'Key Operators'. Exhibition views by Asja Schubert.

Text

Man in office making copies using photocopier, Juliane Bischoff

Jonah Gebka’s publication “Image Runner” is based on a series of drawings and copies that he has produced and developed in the last three years. They show apparently typical actions and gestures of office work, generic pictures of white-collar work without any specific context and not set at any exact point in time, but which are undeniably connected to the present. At this moment, in June 2020, they even resonate with the current situation of the Covid-19 pandemic, a collective state of being isolated and bound to a restricted living and working environment. In this text I examine, in relation to Jonah’s publication, aspects of production, reproduction and the processing of pictures, the visibility and invisibility of work within power structures, and the embodiment of social norms and standardizations.

Production, reproduction, processing

“Image Runner” is being created as part of his exhibition at the Galerie der Künstler in Munich in Fall 2020, and gives him the opportunity to examine his existing image collections composed of drawings, sketches, copies, found photos and prints. We arrange to meet at his studio to talk about his work, and Jonah shares his sifting process with me. He groups motifs and patterns that constantly recur in his drawings and paintings: chequered fabrics, domestic activities, office work, individual figures, assembly instructions in drawings, details of courtyards or depictions of hands. In some cases the works are executed in detail, in others they are studies of surfaces, at times abstract line drawings or images that are heavily distorted and collaged. In almost all cases the initial impulse comes from found photos that Jonah discovers in newspapers and magazines, online, and also by chance in the public sphere. Often, depictions of staged reality guide his choice of motif. He then processes the found images further, appropriates them, and by these means gets closer to their symbolic content. What does the picture mean for the context in which it is set? What does it say about the ideas of the world that underly it?

The selection of motifs in the publication places the focus on the examination of immaterial work and the material handling of paper, which serves as a carrier of information, ideas and means of presentation. They depict people, primarily men, in office or home office situations. They handle paper, photocopiers and computers, thus suggesting cognitive work. Stock images form the foundation of Jonah’s drawings, generic material from image databases that are created and used for illustrative purposes in advertisements and the press.

Jonah processes the found images not only by means of drawing or painting, he also copies, scans and prints over them. As a result, motifs overlap, and the painted picture blurs together with the digitally reproduced one. Tracing and re-painting are also parts of his process towards making the finished picture, as well as fragmentation and re-composition. By using cutups he draws out the details of the pictures, points to certain aspects that might at first appear secondary, and places them in the context of other similar fragments. He uses collaging as a possibility to connect his own drawings and paintings with found material from a general imagery, as “a way to create meaning and order in relation to the world outside”. (Freireiss, 2019, p. 20).

Jonah also includes the reverse sides of the pictures in the reproductions in the publication. The traces of lines can be seen, semi-transparent overlays, leaking photocopies that show the front and the back at the same time. Jonah places the sheets in front of a black background. The contrast highlights the image border. He emphasizes the border of a detail, or cuts the motif that transgresses the image’s space. But Jonah also shows us the flip side of the image production: the scanner or photocopier that generates the reproduction is visible as a black background space. The hand that places the original on the glass pane of the photocopier appears, shifting the focus to the act of creation. Copying, printing, painting over and printing again is part of Jonah’s painting practice. In the final part of the publication he uses a watercolour, which he copies mechanically dozens of times, always using each copy as the original for the next copy. In the process, the original motif recedes more and more into the background, while the colour becomes denser. With increasing reproduction, the machine produces more and more matrix dots, revealing its technical character. By overlaying technically reproduced pictures and his own drawings and paintings, Jonah subtly questions the extent to which the artistic image must still meet the requirements of originality and ingenuity, and how a creative act is defined. At the same time, he casually points to art-historical references to modern and postmodern art, which used techniques of reproduction as an emancipatory act.

The use of the photocopier is also reflected in the title of the publication: “Image Runner” is the name of one of the devices used by Jonah, from the Canon brand. The photocopier, like photography and film, allows mass reproduction and enables, as described impressively by Walter Benjamin, a changed collective perception by means of an altered depiction of reality. Reproduction contributes to the fact that the reception of artworks changes, and as a result, art receives a changed social function. Here, Benjamin saw both the chance to make art more accessible for a wider social group, but also the danger of its instrumentalization for the purposes of politics and capitalism (cf. Benjamin, 1963).

The visibility and invisibility of work

Yet like almost no other equipment, the photocopier is the symbol of the post-industrial age, in which physical labour is being replaced increasingly by cognitive work, and the manufacture of goods is shifting to the southern hemisphere and thus being made invisible. Daniel Bell refers to post-industrial society as the information society, in which capitalist production is less dependent on raw materials than on information and knowledge. Technical advancement is based on value creation due to knowledge production, thus altering both the structures and the value of labour (cf. Bell, 1975).

The notes added to the image part of Jonah’s publication contain keywords and titles of the stock images that served him as models for his drawings: “Man in home office using computer holding paperwork and smiling”, “Co-workers working at office comparing data”, “Financial analyst with document in his hands reading information on computer screen”, “Midsection of businessman using printer in office”, “Two businessmen having discussion in office. Consulting, laptop” or “Portrait of busy male office worker makes voice call discuss documents with partner compare result try to predict wastes for next month. Head executive officer holds balance sheet and mobile phone”.

The photos that Jonah finds in online databases are created to serve as illustrations for reports or to advertise products. They therefore have a communicative aim. In order for them to be used in as varied a manner as possible, and to address as many people as possible, they aim to represent something “typical” or “normal”, as Paul Frosh describes: “advertising images communicate by systematically performing ‘ordinariness’” (Fros,h 2001). By these means they reproduce ideas as to how certain activities, but also the function-holders who carry them out, should look. They strengthen the feeling of supposed normality, which however depicts only a section of society. Rather, they represent a social norm – a norm that is primarily white, male, heterosexual, of adult age and physically healthy. Every characteristic that does not represent this norm must be given its own keywords and sought-for specifically. Public imagery is the product of social contexts. It upholds and at the same time reproduces those social contexts by the visualization and categorization of actors.

Jonah draws from the pool of images that are available in databases and which therefore also to a certain extent reflect the dominant representation of mainly male protagonists, which stands out in the subject matter. Supposedly complicated, cognitive activities – “comparing data”, “discuss documents”, “compare result try to predict wastes for next month”, “financial analyst reading information” – are shown as being carried out mainly by men. The photo of a female character in Jonah’s publication, who is named as such in the comments, bears the keywords: “Irritated Businesswoman Looking At Paper Stuck In Printer”. She represents another aspect of social conditions in patriarchal capitalist systems: Women are associated more strongly with emotional reactions, and where a woman appears here in the context of cognitive work, she generates a problem: paper is stuck in the printer and the situation seems to be intractable, she can only react with irritation. Advertising pictures show (white) men in socially highly-regarded areas of activity, such as “business” in general, while women are still tasked with reproductive, support and care work, or else they are presented in a sexualized or objectified manner, up to and including the non-active naked bodies that advertise goods.

Another feature of the postmodern world of work is expressed in Jonah’s drawings: the performance of work subjects. Andreas Reckwitz describes the structural change in society since the 1970s/80s as a process of “singularization”. Forms of standardization recede increasingly into the background and characteristics such as uniqueness and specialness achieve greater social value. Both the aesthetic and ethical structuring of one’s own life articulates the desire for an expressive, unique self, which is subject to the logic of difference and competition. This is also true in the area of work, where nowadays formal qualifications count for less than the accentuation of a unique profile. The assessment measure is not objective performance, but rather the presentation of one’s own irreplaceability, the subject of work becomes a “performance worker” (Reckwitz, 2018, p. 209).

On the one hand, a constant performance pressure is expressed in Jonah’s drawings, but on the other hand it is revealed to be a repetitive gesture. The sheets held like valuable objects by the protagonists are actually empty. The information to which the captions refer cannot be found. The alienation and dematerialization of the world of work are expressed in repetitive actions. Moments that recall Jacques Tati’s film “Playtime” from 1967, to which Jonah once drew my attention. In the film, the protagonist, Monsieur Hulot, gets lost in an endless complex of identical offices and waiting rooms, as a symbol for the incipient post-industrial society.

Depictions of hands appear repeatedly in Jonah’s works. In the case of the photocopies, they are usually his own. As a painter he addresses the material dimension of picture production and highlights the conditions of production. The photographic print of the hand bespeaks the artist’s preceding presence, it reminds us of the body that made the picture. The hand as a trace appears not only in the form of xeroxed reproduction, but also as a trace of handling, wielding: by the kinks and folds of the page or as fingerprints on the reverse of pictures. By showing touches and traces, the photocopies demonstrate the charged relationships between presence and representation, and imply, in turn, questions as to who is visible and thus ultimately part of a collective structure. The traces bring a temporal, linear aspect to the picture. The work of the printer also forms as sequential lines, by the drawing-in of the paper and the jet of ink as repetitive processes. The technical production of the printed picture thus becomes a metaphor for the production of common social imageries – a sensual experience of society emerges as an everlasting process of production and observation.

Embodiments of social norms and standardizations – the straight line

The personal fulfilment imperative of our present day defines success not only in terms of economic security, but as a permanent reinvention of an interesting, authentic life. The abundance of differences is the decisive feature of global capitalism. From the perspective of Jonah’s work, which is interested in detecting patterns and repetitions, they become a document of fascinating similarity.

The imitation of social ideals, including that of the unique realization of the self, also reproduces the very structures from which these emerge. They are inscribed in the visual world, in patterns of perception, in behaviours, but also in bodies, as shown by Pierre Bourdieu based on the concepts of habitus and hexis (cf. Bourdieu, 1984).

Sara Ahmed expands this idea from a phenomenological perspective, and describes how bodies tend to repeat gestures, which present themselves as effects of previous social practices. They are not so much individual and random, but rather the result of overlapping norms and processes of standardization (cf. Ahmed, 2006, p. 553). Paradoxically, the constant continuation makes the conditions of their origin invisible. They become automated actions, which dictate the directions and thus make certain consequential actions more probable than others. Following patterns generates fewer sources of friction, and power structures perpetuate. The focus of Ahmed’s analysis is the relationship between directions and orientations and the reproduction of norms and conventions. She uses the metaphor of the line – as conceptual directions as well as physical movements –, which presents itself in heteronormative societies as a straight line: “Lines are both created by being followed and are followed by being created. The lines that direct us, as lines of thought as well as lines of motion, are in this way performative. […] We find our way, we know which direction we face, only as an effect of work, which is hidden from view” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 555).

The aspect of tracing lines and thus the repetition and renewal of norms can also be found in Jonah’s depictions of work as continuous, recurring gestures. Learned procedures that are socially prescribed and accepted are repeated, because they are rewarded. Following certain lifestyles promises culmination in success. They are reproduced, and power structures become consolidated. Ahmed relates this idea to the body: “The normative dimension can be re-described in terms of the straight body, a body that appears in line. Things seem straight […] when they are in line, which means when they are aligned with other lines. […] Think of tracing paper. Its lines disappear when they are aligned with the lines of the paper that has been traced: you simply see one set of lines. If all lines are traces of other lines, then this alignment depends on straightening devices, which keep things in line, in part by holding things in place. Lines disappear through such alignments, so when things come out of line with each other the effect is ‘wonky’” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 562).

In Jonah’s pictures, the process of drawing and printing over the images causes a blurring of the lines. Minor shifts lead to the dissolution of prefabricated forms, until they merge completely into a colour field and can no longer be recognized, as in the case of the final drawing in the publication. In contrast, he creates new forms by cutting out, adding and re-composing fragments. What is articulated here is not any loud criticism of social conditions, but rather small gestures, refusing to leave found images unchanged or unchallenged, to touch them, shift them, to disorient them a little, while looking in different directions and thus “making lines that do not reproduce what we follow, but instead create new textures on the ground” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 570).

Juliane Bischoff, 2020

Bibliography:

Ahmed, Sara (2006). Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology. In: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. Vol. 12, Nr. 4, Durham: Duke University Press, p. 543-574.

Bell, Daniel (1975). Die nachindustrielle Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Benjamin, Walter (1963). Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1984). Die feinen Unterschiede. Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Freireiss, Lukas (2019). Radical Cut-Up. Nothing Is Original. In: Id. (ed.): Radical Cut-Up. Nothing Is Original. Amsterdam: Sandberg Instituut/Berlin: Sternberg Press, p. 7-25.

Frosh, Paul (2001). Inside the Image Factory: Stock Photography and Cultural Production. In: Media, Culture & Society. London: Sage Publications, p. 625-646.

Reckwitz, Andreas (2018). Die Gesellschaft der Singularitäten. Zum Strukturwandel der Moderne. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Translated from German into English by Carolyn Kelly.

Download as PDF

003

How To

Galerie der Künstler:innen, Munich, 25.06.2019 – 30.06.2019

Part of the group show 'Tacker'. I presented nine works of the series 'Alternatives' as well as the publication 'How To'. The series shows concrete actions, such as copying, vacuuming or raking leaves. The multiple realization of these motifs in paint and the resulting, slightly different images are installed on the wall as an interrupted sequence. The take away publication 'How To' was located in a sober brochure box attached to the wall. It combines found representations from various assembly instructions with my own drawings. The instructions informational aesthetics are progressively called into question by their repetition, distortion and exaggerated juxtaposition.

002

Diploma

Academy of Fine Arts, Munich, 07.02.2018 – 11.02.2018

A selection of small-format works on paper, the series “Background” consisting of 24 parts, and the publication “Companion” were on view at my diploma show. The works dealt with questions of reproduction as well as the relationship between motif and edge of an image. In addition to empty landscape views, whose romantic promise is broken by analog and mechanical reproductions, some of the works show busy men pursuing ordering activities. In the take away publication “Companion” two anonymous protagonists talk about the surface of a picture-like object. Exhibition views by Sebastian Schels.

001

Boxenstop I

Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, 09.06.2017 – 25.06.2017

With 'Boxenstop I', the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung Munich, in cooperation with the Printmaking Workshops of the Academy of Fine Arts Munich, realized an exhibition project that was conceived exclusively for the display cases in the Pinakothek der Moderne. It was preceded by a competition organized by the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung Munich, in which 12 artistic positions were juried out of 60 proposals. My presentation consisted of sixteen sheets arranged in a checkerboard fashion in one of the display cases. In addition to landscapes, plant still lifes and figures, the images also show motifs that are only remotely reminiscent of an object. In some cases the watercolors and ink drawings are overprinted with an inkjet printer, so that original and reproduction can no longer be separated.